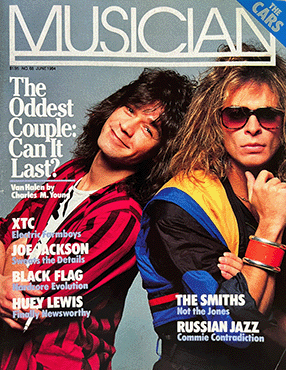

The Oddest Couple: Can it Last?

The article below was originally published in the June 1984 Musician magazine. And was written by Charles M. Young

by Charles M. Young

Page 3

Even if Roth’s singing remains offensive (he doesn’t sing so much as exuberate), you can watch the light show, which puts Close Encounters of the Third Kind on the level of a wienie roast. Or you can watch Michael Anthony throw his bass off a stack of amplifiers and stomp on it. Or you can figure out how Alex Van Halen could possibly play so many drums. Or you can wonder what Roth and Eddie Van Halen are doing in the same band. It’s hard to imagine two guys with less in common psychologically, yet together they seem to make a complete personality. Extrovert balanced by introvert, logic by intuition entertainment balanced by artistry. Sometimes it comes together, which is thrilling, and sometimes it sounds like all four of them are playing different songs as fast as possible, which is pretty funny. Attempts at intricate ensemble playing-such as voice/guitar duels-appear to leave the participants as bewildered as if they were actually talking to each other. This they compensate for with long solos. If the hero is the guy who can absorb the most absurdity, as the existentialists propound, Van Halen cops this year’s Camus Cup.

Unlike most guitarists, Eddie smiles and rarely grimaces. But even when 20,000 kids are chanting. “EH-DEE! EH-DEE!” the smile is shy. He just doesn’t need, as he says, humans. What he needs is a 60,000-watt sound system with 600 speakers to make new noises. And if 20,000 kids happen to be sitting there listening at 116 decibels, it’s okay, but he’s going to get on with arpeggiating all over his guitar neck. Which is the amazing thing about Eddie Van Halen: he arpeggiates and doesn’t jerk off. Neither does he play bar chord progressions, as does everyone from the Ramones to Def Leppard. He plays actual, honest-to-God guitar riffs, which nobody has done on a consistent basis since the heyday of Hendrix, Page and Beck. “Unchained,” “Hot For Teacher,” “Panama,” “Ain’t Talkin’ ‘Bout Love,” “You Really Got Me”-it’s ecstasy for guitar worshippers and slushjumpers (ever hear a crowd cheer louder than 600 speakers?). Or as Al Jolson and David Lee Roth would say, “is everybody happy?”

YEAHHHHHHHHH!!!!!!!!!

There is, of course, a price to be paid: twenty percent of the upper end of Alex Van Halen’s hearing, according to a recent article in Modern Drummer.

“It’s thirty percent now,” Alex chuckles backstage in a dressing room. “I did that interview five months ago.”

Another ten percent after a third of the tour?

“I’m hoping it will come back. There are certain frequencies which do regenerate in your hearing. I notice myself going “Huh? and Whah?’ a lot more these days. It’s annoying but it you dance, you gotta pay the piper. Remember I’ve been doing this since I was twelve years old, eleven years with this band. I don’t know if people are generally aware of how decibels work, but 113 is twice as loud as 110, 116 is twice as loud as 113. Back by the drums, it’s over 130. We had a doctor come in once to measure and he just said, ‘Give me back my dB meter. I don’t ever want to see you again.””

Broader and more muscled than older brother Eddie, Alex throws back his head and laughs.

“Most of the people I know who have been playing loud music a long time are basically deaf. Pete Townshend, you could stand in front of his face and say, ‘Hey, Pete, I’m fuckin your wife, and he’d nod his head and go. “Yeah, yeah, yeah It’s a shame it has to happen. Because without ears, you won’t be able to hear music anymore. At some point they’re just going to have to figure out a way for musicians to hear everything while they’re playing without destroying their ears”

(It should be pointed out that this interview took place before the show, which had much to do with Alex’s hale-and-hearty attitude. After the show, the guy looks dazed and a little mournful, crucified in the ears)

When Eddie got a paper route at the age of fourteen to pay for his set of drums. Alex stayed home and played them. Eddie soon switched to guitar, found a hero in Eric Clapton (used to reserve bowling lanes for himself in Clapton’s name) and started a succession of bands: Trojan Rubber Company. Bald Genesis, Mammoth and Van Halen. Their father was not pleased.

“He was a professional musician himself, and he knew what you had to go through to raise a family or lead any sort of good life,” says Alex, recently married, more recently divorced, and bummed out. “That’s where I think Van Halen is a lifestyle.

Dave used to have an expression that carries a lot of truth: we aren’t this way because we’re in a rock band. We’re in a rock band/because we are this way. You can’t force it. You can’t fake. Traveling ten months a year, being in the studio, staying in close quarters with three other humans, it can get on your nerves if you’re really into it. If you approach it as a business, a means to an end, you’re in the wrong place.”

Massive, gnarled and fat-fingered, Alex’s hands are the sort you would expect on guy who’d been tearing face masks off of quarterbacks for the LA Raiders.

“See this?” asks Alex, indicating a jagged brown scar on his left forearm. “Hey, I bet fifty grand for this. You put your arms together and drop a cigarette in the middle. Four hours of smelling burned skin. It was like fried chicken after a while.”

For four hours they sat there with a burning cigarette between their arms?

“Not a cigarette. Two packs. It burns and burns and burns. The first guy to move his arms loses.”

Jesus

“Jesus? You wanna see Jesus? I was at a friend of mine’s birthday party at a Japanese restaurant. There was a little grill at the table where they cooked the food. And I finished. And I tipped a few sakes. And I decided. Come on, let’s dance naked.’ So I took off my clothes and got on the table. I was having a pretty good time when I stepped on a sake glass and fell right on the grill. ZHZHZHZHZHZHTTTTI! I burned the shit out of myself. Ended up at the same hospital where they took Richard Pryor.” Alex laughs uproariously and rolls up his sleeve, revealing a large, squarish scar. “What’s it look like? The Shroud of Turin, right?”

“That’s my Uncle Otto,” says David Lee Roth, pointing to a short but erect old man. “He’s eighty-one and walks five miles to work three days a week. And people ask me how long I think this can last” Turning his attention back to a large group of concerned relatives backstage in Chicago, Roth loudly explains that when critics use the term “gleefully obnoxious,” it means “Mercedes”

“That’s our grandmother there,” says Roth’s cousin Lori Simon. “The last time she saw a concert, she just turned off her hearing aide and she could hear everything After tonight, she won’t talk about anything else for months. We gave her a video of “Jump and it put five years on her life.”

Having no relatives to entertain in the immediate geographic vicinity, Michael Anthony sits in a side room expounding bass philosophy.

“When I started playing bass, everyone said, “Well, the bass isn’t the lead instrument, so you’ll never be a front man. You’re just going to stand in back by the drums and play.” says Anthony, who has never stood in back by the drums and played. At first he was singing lead, booking the gigs and driving the van (as well as playing bass) for a band called Snake. Then he opted for a more subordinate role with Van Halen, if you can call wearing gold lame jumpsuits, singing backup, throwing your bass off of a twenty-foot stack of amps and stomping on it (kids never tire of broken guitars subordinate.

“If I had my way, I’d just wear a T-shirt and play,” says Anthony. “I’m a musician first. I’d still move around, “cause that’s what I like to do, but, ya know, we got Dave who’s always pushing-choreograph! choreograph! He’s always-been-that kind of person, more into the show. I’m sure stomping on the bass looks good out there in the audience. It’s just so far from what a bass player would normally do. So what the heck.”

How’s the hearing?

“Very good. I’ve got the best spot onstage monitor-wise. On Ed’s side, you get all that guitar with those high frequencies that, by the time they reach me, aren’t all that piercing. On my side, it’s all bass and just enough drums to where I feel comfortable. When I jump on the drum risers, standing next to one of those cymbals is like…” Anthony grimaces with pain. “It doesn’t compare to where I’m standing. He’s got all this high- end stuff just blazing up there, plus he’s got one of Ed’s cabinets a two-by-twelve, right there in his ear. If I was behind a kit like Ars-the level it has to be pumped just so he can hear the set-it would collapse my head.”

“At the speed and volume Van Halen plays, you walk a very fine line between having it too loud-in which case it becomes a blurge, a totally inaudible mess-and having it too soft, in which case you can’t feel it,” says Nigel Buchan, current sound engineer for Van Halen, former sound engineer for Billy Squier, Judas Priest, Uriah Heep, Wishbone Ash, City Boy. Coliseum, Andrew Lloyd Weber and Rockpile. “You have to feel rock ‘n’ roll as well as hear it, have both clarity and punch. A band this powerful visually must be equally powerful musically. The kids expect to hear what they see in David Lee Roth.”

Buchan has a humongous sound system (see instrument box for details) to create just that aural environment. You can tell when he’s achieved it because he’ll start dancing at the soundboard. “And if I start dancing,” says Buchan, who has lost none of his hearing, “I very well know that 15,000 kids around me are going to be dancing”

That’s when his job’s easy. When it’s difficult is getting the four musicians to dance.

“I have a different view of mixing than probably a lot of engineers,” says Buchan. “I don’t start with myself. I start with the source. I can’t deliver the sound to the audience if the musician that is delivering the sound to me is not happy. I set up the monitors myself. I sit down with the band, hear exactly what they want to hear, when they want to hear it and at what volume. I stand there with the band and call out frequencies to make the sound better: We need 5 dB at 2k’ or ‘We’ve got too much low end so let’s take minus 6dB at 160 hertz, and sweep the spectrum until the monitoring system is crystal clear.

“Every guitarist has a sound. The Eddie Van Halen sound is very, very special. It’s hard to talk about, but it has a warmth. Almost every name guitarist in the world, when they do their solos, makes the most awful screeching sound, like cats squealing. When Ed plays a solo, it doesn’t screech. We do a lot of work to get that sound that a lot of musicians wouldn’t bother with. Spend hours revalving his amps or whatever. But Eddie lives for his guitar, lives for hearing it the way he wants to hear it. If you put it into a color, it would be brown. That’s what he calls the brown sound.”

“This is me and my brother on New Years Eve. I’d just finished pukin,” says Eddie Van Halen, slipping a cassette into a portable four-track a few hours after the show in his hotel room. An unearthly bass and drums duet comes over the tiny speakers as he keeps a couple of Pall Malls lit-one in his mouth, one burning a hole in the lamp table. Every ten seconds or so, he flicks Fast Forward to pass over the noodling and arrive at some musical point he seems desperate to communicate. Contrary to rock ‘n’ roll custom, he carries no “road tapes” of his favorite music. No old Motown, no Beatles, no Stones, no Marley, nothing contemporary to hear what the competition is up to. Just a pillowcase of cassettes documenting his own endless quest for new noise: the soundtrack to his wife’s last movie, The Seduction of Mimi, the original “1984” (an album in itself) from which the 51-second album version was excerpted, and a synthesizer concerto of “bathtub farts.”

“This one is what makes me think I’m nuts,” says Eddie, popping in a cassette that could be called Instant Alpha Waves for its primordial effect, music from before the cerebral cortex was invented. “That’s Marvin Hamlisch’s piano. Valerie and I rented his beach house…there I’m scraping with a knife…plucking the strings harmonically… that’s a drumstick on the cover…muffling the strings and hitting the keys… there I’m throwing a fork at it…that’s Valerie going. Shut up, I’m watching David Letterman….”

Eddie picks around in his cassette pile for a moment and then gets to the point: “Do you think I’m strange?”

Well, yeah. There is something eerie about Eddie Van Halen, almost holy, Michael Jacksonly. Anyone who can throw a fork at a piano and make more music than most people on the charts do with entire bands-that’s very very strange. Just being in its presence, let alone living with it is a little frightening. The guy has no persona, no wall of normal behavior between him and his suspicious world. Just pure essence of feeling. When he likes you, he kisses you. When he’s frustrated, he throws one of his delicate hands into the wall and busts a knuckle. It would appear to be the only route to the Brown Sound. “Alex originated the term, and Nigel understands it, and Donn Landee understands it better than anyone. It’s tone. It’s wood, as opposed to cinderblock. You can have the AM radio in your car blaring, and the actual sound level is not loud at all, but it sounds hurting to the ear. Whereas you can have a nice home stereo at much higher dB level but it’s warm. One is brown, and one isn’t”

But Van Halen is the band that achieved a portion of its notoriety by contractually forbidding brown M&Ms in their hospitality rooms. “M&Ms are chocolate. They have nothing to do with sound”

Brown doesn’t make any more sense. It’s a color that has nothing to do with sound.

“It has nothing to do with M&Ms! It’s wood! Imagine some- one hitting a piece of wood as opposed to metal or cement. It develops a tone that is pleasing to the ear. It’s just a word. I could call it anything, but the only word I can think of is brown. The brown. I am into the brown. They should add a few words to the dictionary. There are a lot of things the dictionary doesn’t explain.

For a dictionary to explain these things….

“They’d have to feel them.”

Where would a lexicographer feel the brown sound to come up with a definition?

“There’s a lot on 1984. Al’s snare drum. Instead of shshshsk, it goes toonk. The only way I can relate this is to tell you who doesn’t have it, and I don’t want to put anyone down in print. It’s something that hurts when it’s not there. And when it is there, no matter how loud it is, it feels warm. Most people cannot understand the brown, can’t put a finger on it, but it affects them subliminally.”

Let’s follow up on subliminally.

“People can sense the brown and not know what it is”

Sometimes in writing a passage it will just be there, and sometimes either you blow it or something as small as a comma will get changed and there goes….

“Your brown sound.”

Yeah.

“So you’re asking me what it is?”

There’s still no working definition, no way to convey….

“Forget it. You can’t. It’s too deep, and they don’t care to find out. It’s a warmth concerning anything, man. It’s like when you really love someone and you’re getting the feeling back. It’s tone. It’s feeling. It’s warmth. And only the 5150s know.”

HOW NOW, BROWN SOUND?

Sound engineer Nigel Buchan delivers the brown sound to the world through an Audio Analysts P.A. consisting of sixty S-4 cabinets with 1,000 watts and ten speakers each (two 18-inch, four 10-inch, two horns, and two high frequency units, all JBL). The system is highly modular, taking just an hour and forty-five minutes to go from truck to blasting.

The monitor system, which has wedges (with two 15- inch, two horns and a high frequency unit) buried under grates all over the stage in strategic areas, contributes another 16,000 watts. “That’s bigger than most bands on the theater circuit take out for their house system,” says Buchan, “Van Halen plays at a staggering volume onstage. 134 dB. And we have no monitoring problems whatsoever This must be the first band in history to ask for the monitoring system to be turned down.”

Through this aural colossus, Eddie plays a Kramer copy (“The simplest, most stripped down form of musical instrument there is.”) of his original customized Stratocaster that is now out to pasture except for studio work. His amps are the usual old Marshalls. His synth is the Oberheim OB-8.

Michael Anthony has four basses of choice. 1) a Yamaha Broad bass 2000 (never actually produced in the States) with Schacter pickups and a neck he has narrowed for better access to the top frets: 2) a custom Zeta in the shape of a Jack Daniels bottle with pickups in the saddle of the bridge (“sounds punchy as hell”), a body carved by Charvel and a paint job by Chuck Wild Studios; 3) a Kramer for throwing off the top of his amp stack (“I’ve never had a problem with the neck snapping and I jump on it full force.”) and 4) a Steinberger with split EMG pickups for studio use As for amplifiers, he’s all SVT onstage and in the studio prefers an old Ampeg B-15 with the flip head.

Alex throttles a drum kit that could double as the set of the next Star Wars installment: two double-headed kick drums in the middle (24-inch and 26-inch) and two single- headed kick drums (same width) on the outside. Inside each he has mounted a radial horn. All the shells are Ludwig for aesthetics with Simmons electronic drums mounted inside. Across the top he has mounted a set of Octabans and keeps his high end blazing with Paiste cymbals.