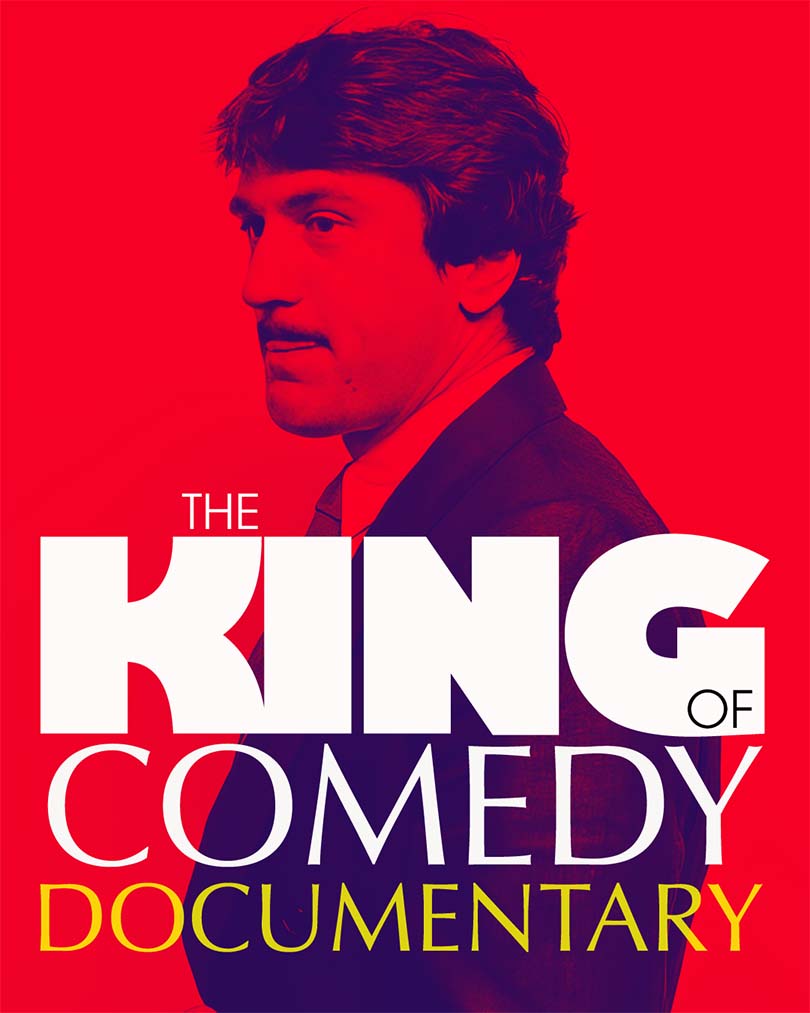

The King of Comedy Documentary | Martin Scorsese & Robert De Niro

Learn something new about Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro’s cult classic The King of Comedy. The King of Comedy is a 1982 American satirical black comedy directed by Martin Scorsese and featuring Robert De Niro, Jerry Lewis, and Sandra Bernhard.

The screenplay, written by Paul D. Zimmerman, explores the dark side of fame and the blurred lines between reality and delusion. The film follows Rupert Pupkin (played by Robert De Niro), an aspiring stand-up comedian with grandiose dreams of fame. Despite his lack of talent and social skills, Rupert is determined to make it big. After repeated rejections by his idol, talk show host Jerry Langford (played by Jerry Lewis), Rupert’s obsession spirals out of control. He kidnaps Langford, holding him hostage in exchange for a chance to perform his comedy routine on live television. What unfolds is a biting commentary on the desperate lengths some will go to for their fifteen minutes of fame, set against the backdrop of a media-obsessed society.

00:00 – Start

00:58 – The screenplay is written

01:53 – De Niro buys the screenplay

02:36 – De Niro sells The King of Comedy to Marty

02:58 – Real-life horrific events

04:35 – Looming directors strike

05:10 – How Rupert Pupkin is like other Scorsese characters

07:10 – Raging Bull

07:50 – The Aviator

08:20 – The Last Temptation of Christ

09:22 – De Niro transforms into Rupert Pupkin

09:56 – Fat Vinny

11:14 – Casting Jerry Lewis as Jerry Langford

11:41 – Drunken mess

12:01 – De Niro didn’t want Lewis at first

12:45 – De Niro pushes Lewis’ buttons

13:33 – The supporting cast

14:24 – Cameos

14:50 – The Clash

15:20 – De Niro’s really good buddy

16:46 – The look of The King of Comedy

17:19 – Other movies similar to The King of Comedy

17:29 – Sunset Boulevard

18:56 – Play Misty for me

21:04 – The Fan

22:16 – Reception for The King of Comedy

22:58 – The influence of The King of Comedy

23:29 – The Comedian

23:52 – Joker

24:52 – Paul Zimmerman post premier

26:46 – The King of Comedy of trivia

The King of Comedy script:

Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy is a film that masterfully blurs the lines between satire and psychological drama, defying easy categorization. It’s a stark departure from the visceral intensity of Scorsese’s earlier works like Taxi Driver or Raging Bull. Instead, The King of Comedy ventures into a more arid and unsettling territory, diving deep into the psyche of its delusional protagonist, Rupert Pupkin, played by Robert De Niro. De Niro delivers one of his most complex and unnerving performances, embodying the desperation of a man obsessed with fame at any cost. The result is painful, eerie, and ultimately ahead of its time.

The film’s origins trace back to 1970 when Newsweek film critic Paul D. Zimmerman, inspired by an episode of “The David Susskind Show” about autograph collectors and an Esquire piece on a man obsessed with “The Tonight Show,” wrote a 300-page unpublished novel that he later adapted into a screenplay.

The script caught the eye of legendary producer Robert Evans, who then passed it to director Milos Forman. Forman was intrigued enough to move into Zimmerman’s home, where they spent two months working on refining the screenplay. But, their collaboration eventually hit a dead end, creating two distinct versions of the script—one that Forman preferred and another that Zimmerman favored. Forman moved on to develop his version with writer Buck Henry, but this iteration failed to gain traction. Forman ultimately shifted his focus to directing his acclaimed movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

By 1974, Zimmerman’s screenplay landed in the hands of Martin Scorsese. Scorsese dismissed the project at the time, seeing it as a one-joke movie because he was busy with other commitments. But, he agreed to pass it on to Robert De Niro, who saw potential in the story and later bought the rights to the screenplay in 1976. De Niro’s enthusiasm breathed new life into the project, and by 1978, De Niro had secured financing. And in early 1979, he convinced Michael Cimino, fresh off his success with The Deer Hunter, to direct. Unfortunately, Cimino became entangled in the post-production debacle of Heaven’s Gate, leaving De Niro without a director.

So De Niro approached Scorsese again, catching the director at a vulnerable moment. Scorsese, hospitalized for exhaustion, was swayed by De Niro’s pitch of making a ‘leisurely’ New York film. Reflecting on the decision later, Scorsese admitted, “[De Niro] made it seem like a lark . . . and I was exhausted, so I was susceptible to an easy film.”

De Niro may have believed it would be an easy film to make, but between the time Scorsese agreed to make The King of Comedy and its premiere, chilling real-life events unfolded, mirroring the themes of celebrity obsession and dangerous fandom that the film was exploring. In December 1980, John Lennon was tragically gunned down by a fan whose warped quest for fame turned deadly. Just months later, in March 1981, John Hinckley Jr. attempted to assassinate President Reagan, driven by an unhealthy obsession with Jodie Foster and the character of Travis Bickle from Scorsese’s “Taxi Driver.” The following year brought another horrifying incident linked to Scorsese’s work: Arthur Richard Jackson developed a dangerous fixation on actress Theresa Saldana after seeing her in Scorsese’s “Raging Bull.” Posing as Scorsese’s assistant, Jackson obtained Saldana’s address from her mother. He then ambushed Saldana outside her West Hollywood home in broad daylight, stabbing her repeatedly, puncturing a lung, and nearly ending her life.

Reflecting on these events, particularly the attempted assassination of President Reagan, Scorsese would later say, “I seriously considered not making films anymore, if that’s what it (the reaction to them) was going to be like. But then I got this three-page letter from a lady, and in the last paragraph, she wrote something like, ‘Please don’t stop making the films, because, remember, that for the one crazy or stupid person who acted that way after seeing Taxi Driver, think of all those who saw it and were enriched by it.'”[Toronto Film Festival]

The other challenge Scorsese was facing was a looming director’s strike. So Producer Arnon Milchan insisted they start shooting by July 1st, a full month before Marty would be ready. As a result of the hasty beginning, Scorsese was exhausted, De Niro harried, and the production crew disorganized. Scorsese later said, “Physically I didn’t feel ready. I shouldn’t have done it and it soon became clear that I wasn’t up to it. By the second week of shooting I was begging them not to let me go on. I was coughing on the floor and sounding like a character from The Magic Mountain!”

Writer Paul Zimmerman said that although he created the character Rupert Pupkin, Scorsese and De Niro made it their own. He noted that Scorsese toughened the script to accent the main character’s alienation, his favorite theme, and admittedly put much of himself into the characters.

Scorsese’s characters often struggle with profound loneliness and disconnection from society. Like Travis Bickle, the protagonist of Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, Rupert is a quintessential example of loneliness personified. His isolation is deeply embedded in every aspect of his life, from his physical environment to his psychological state.

Pupkin is profoundly lonely, living in a world almost completely disconnected from meaningful human relationships. Despite his outward attempts to appear confident and friendly, his life is marked by isolation. He lives with his mother, who he constantly yells at from the basement of their home—a space that serves as both his refuge and prison. This basement symbolizes his separation from the world, where he practices his monologues and dreams of stardom yet remains cut off from real connections.

Many of Rupert’s social interactions are imaginary. He frequently fantasizes about being close friends with Jerry Langford, the famous talk show host he idolizes. In his mind, Jerry admires and respects him, inviting Rupert into his world of celebrity. However, these fantasies only underscore his detachment from reality and the absence of genuine friendships or relationships. His few attempts at real interaction, such as with Rita, the woman he briefly dates, are awkward and unfulfilling. Rupert’s inability to connect with others on a meaningful level leaves him isolated, fueling his desperation to be noticed as someone important in the eyes of the world.

This theme of isolation echoes throughout Scorsese’s work. In Raging Bull, Jake LaMotta’s life is similarly shaped by loneliness, stemming from his inability to connect with others and his self-destructive behavior. Jake, like Pupkin, is trapped in a world of his own making, where his intense physical and emotional battles drive away those closest to him. His life, marked by violence and turmoil, ultimately leaves him alone, reflecting the tragic consequences of his choices.

Howard Hughes in Scorsese’s The Aviator mirrors this detachment from reality. Hughes, like Rupert, creates a world in his mind where he is in control, admired, and invincible. His obsessive-compulsive disorder and paranoia lead him to construct elaborate fantasies about threats and control, pushing away the people around him. Both Rupert and Hughes are trapped in their fantasies, unable to forge meaningful relationships, ultimately isolating themselves in their quest for significance.

Even in a spiritual context, Scorsese explores this theme of isolation. Willem Dafoe’s portrayal of Jesus in The Last Temptation of Christ presents a figure deeply isolated by the weight of his divine mission. Jesus grapples with his role as the savior, feeling alienated even as disciples and followers surround him. His internal struggle with his identity and destiny creates a profound sense of loneliness that resonates with the experiences of Pupkin, LaMotta, and Hughes.

Rupert Pupkin is a quintessential Scorsese antihero. His delusions of grandeur, isolation, and moral ambiguity connect him to the rich tapestry of Scorsese’s most iconic characters. Through Pupkin and others, Scorsese explores the deep and pervasive loneliness that stems from living in a world of internal conflict and disconnection, a theme that runs consistently through his body of work.

De Niro’s preparation for his portrayal of Rupert Pupkin was characteristically thorough and unconventional. To capture the essence of his character, De Niro immersed himself in various aspects of Pupkin’s world.

He delved into the comedy scene, shadowing stand-up comedian Richard Belzer and observing others, including his future co-star Sandra Bernhard. This helped De Niro understand the nuances of comedic timing and stage presence that Pupkin aspired to achieve.

De Niro also jumped into the realm of celebrity obsession and autograph collecting while preparing for his role. One night at 3 a.m., he was approached by Vinny Gonzales, better known as “Fat Vinny,” a passionate fan of the rock band KISS and a committed Hollywood autograph collector. Recognizing Vinny as the perfect person to study for his portrayal of Rupert, De Niro invited him to dinner with Scorsese. De Niro’s fascination with Gonzales grew, leading him to visit Vinny’s home, meet his parents, and ultimately use him as inspiration for the character of Pupkin. De Niro even offered Gonzales a job as his driver, but Vinny declined, not wanting to miss the upcoming KISS tour. Gonzales makes a brief cameo appearance in the film.

De Niro’s commitment to authenticity extended to Pupkin’s wardrobe as well. Collaborating with director Martin Scorsese and costume designer Dick Bruno, De Niro scoured Times Square stores that catered to magicians and performers. De Niro said they found Pupkin’s stand-up outfit in the display window at Lew Magram Shirtmaker to the Stars store, taking it exactly as it appeared on the mannequin. A twist emerged years later when the outfit was being auctioned: the jacket had a Barneys label, a different New York retailer, on the inside. It’s unclear whether De Niro misremembered the store where they found the outfit or if Lew Magram was selling second-hand clothing. Dick Bruno designed the other Pupkin outfits.

Writer Paul Zimmerman initially wrote the screenplay with talk show host Dick Cavett in mind for the role of Langford, but Scorsese wasn’t interested in Cavett. When Scorsese envisioned the character, he immediately thought of real-life talk show icon Johnny Carson and approached him for the role. However, Carson declined the offer, not wanting to do the multiple takes that the movie required versus doing one take on TV.

Orson Welles was considered for the role, along with Frank Sinatra, which led to the rest of the Rat Pack into consideration. Scorsese’s thoughts drifted to Dean Martin, but that train of thought quickly detoured to Martin’s old comedy sidekick, Jerry Lewis. Once a Hollywood heavyweight, Lewis was now more famous for his annual 24-hour telethon than anything else. His movie theater chain had just gone bankrupt, he hadn’t starred in a movie in almost a decade, and he had never tackled a dramatic role. So it wasn’t a shocker when De Niro initially balked at casting Lewis. But after a string of meetings and grilling Jerry about the character, De Niro came around to the idea of him playing Langford. Once the deal was inked, Lewis recalled De Niro calling him up and bluntly saying, “I need you to know that I really want to kill you in this picture. We can’t socialize, we can’t have dinner, we can’t hang out.”

Just like he did with Joe Pesci in Raging Bull, De Niro decided to go off-script to stir up a raw reaction from Jerry Lewis for a key scene in The King of Comedy. The scene involved Rupert Pupkin showing up uninvited at Jerry Langford’s country house, and De Niro knew he had to push Lewis’s buttons to get a genuine response. Without Lewis knowing the cameras were rolling, De Niro, positioned just off-camera, started throwing anti-Semitic slurs at him. Lewis, blindsided by the shocking insults, erupted in fury, delivering a powerful performance in the process. It wasn’t until later that he realized he had been manipulated into that state. Even though De Niro later came to apologize, Lewis was so infuriated that he vowed never to work with De Niro again.

The supporting cast in The King of Comedy is outstanding. Jerry Lewis delivers a surprisingly nuanced performance as Jerry Langford, a celebrity both revered and reviled by his fans. In her first starring role, Sandra Bernhard shines as Masha, a wealthy and delusional groupie whose manic intensity matches De Niro’s portrayal of Rupert. Even the more minor roles, like Diahnne Abbott as Rupert’s skeptical girlfriend and Catherine Scorsese as his overbearing mother, add to the film’s atmosphere of suffocating desperation.

Abbott, who was De Niro’s wife at the time, also appeared in Taxi Driver. The voice of Rupert’s mother, heard offscreen, is provided by Scorsese’s real-life mother, Catherine, who appeared in several of his films, including a documentary about his parents. The film also features other members of Scorsese’s family, including his father, Charles, and his daughter, Cathy, who plays an autograph collector. Even Scorsese himself makes a cameo.

Additional cameos include members of The Clash, one of De Niro and Scorsese’s favorite bands, who were in town playing shows at the Bonds Casino. In the same scene, you can spot musician Ellen Foley. Foley was the female voice in Meat Loaf’s hit song Paradise by the Dashboard Light. She doesn’t look the same in the video because that’s a different singer, Karla DeVito, who is lip-synching to Foley’s voice. You can also spot, although unconfirmed, actor Gérard Depardieu, a friend of De Niro. I mean a real good friend of De Niro’s.

Johnny Carson’s real-life producer, Frederick DeCorova, appears as the producer of Jerry Langford’s show. Other notable cameos include Dr. Joyce Brothers, Tony Randall, and Liza Minnelli, who played themselves. Menelli’s part was cut, but can be seen in the DVD extras.

Two of the more interesting cameos involve lesser-known individuals. Chuck Low became friends with De Niro after serving as his landlord in New York City and asked to be in one of his films. De Niro obliged, giving him a background role in The King of Comedy as a character mimicking Pupkin in hopes of stealing his date. In the original script, Low’s character succeeds, but this scene was cut. You might also recognize Low from other De Niro films like Goodfellas.

The other cameo is by Martin Scorsese’s cook and assistant, Dan Johnson, who appears in a cut scene antagonizing Pupkin. During production, Johnson and musician Robbie Robertson go out for a beer, but tragically, Johnson dies suddenly of acute meningitis upon returning home. Scorsese dedicated the film to Johnson, and Robertson wrote the song “Between Trains” on the soundtrack in his memory.

After a solid critical appreciation for how he had shot Raging Bull, Scorsese felt that The King of Comedy needed a rawer cinematic style, using more static camera shots and fewer dramatic close-ups. Scorsese used the film Life of an American Fireman to guide this visual style. Knowing nothing about how a TV studio works, he turned the directing reins over to Jerry Lewis for those parts. They shot the scenes with TV studio cameras to mimic the television look and transferred that to film.

The King of Comedy was different from most movies in 1983, but it wasn’t entirely without precedent.

Sunset Boulevard and The King of Comedy, separated by decades, share striking parallels in their themes and production. Both films, directed by visionary filmmakers—Billy Wilder and Martin Scorsese—delve deep into the psyche of fame, offering a sharp critique of the celebrity culture that drives individuals to extreme lengths for recognition, often leading to self-destruction.

In Sunset Boulevard, Wilder dissects the dark side of Hollywood through the tragic character of Norma Desmond, a once-iconic star now trapped in a world of delusion, unable to accept that her time in the spotlight has passed. This theme of living in a fantasy, disconnected from reality, resonates strongly with Pupkin.

Both films cast actors who were out of step with Hollywood. Wilder’s choice of Gloria Swanson, a silent film star whose career had faded, to play Norma Desmond mirrored her life in a haunting way. Likewise, Scorsese cast Jerry Lewis, whose comedic career had diminished by the 1980s. However, both movies also featured A-list actors of the time—William Holden in Sunset Boulevard, a leading man at the peak of his career, and Robert De Niro in The King of Comedy, one of the most respected and sought-after actors of his generation.

The theme of obsession takes center stage in the films “Play Misty for Me” and “The Fan.”

Play Misty for Me is Clint Eastwood’s directorial debut and, ironically, director Don Siegal’s acting debut. It features a fan’s obsessive love for a radio DJ, played by Eastwood, which escalates into dangerous territory. The fan’s inability to distinguish between admiration and possession parallels Rupert’s fixation on Langford. Both films explore how obsessive behavior can lead to violence and a complete detachment from reality. The difference lies in the object of obsession—while Evelyn, the fan played by Jessica Walter, is fixated on a romantic relationship, Rupert is fixated on fame and validation.

As a film, “Play Misty for Me” is a solid watch for a lazy Sunday afternoon—not a masterpiece, but certainly entertaining. Unlike De Niro, Eastwood is not entirely convincing in his role as a radio DJ and is outshined by his co-star, Jessica Walter. Walter nails the role of the crazy girl from a one-night stand, transforming what starts as a casual hook-up into a full-blown horror show. With a wicked grin and eyes that scream “red flag,” her character takes “clingy” to a new, terrifying level.

Eastwood’s Play Misty for Me and Siegal’s Dirty Harry were released in 1971. In a bit of cinematic cross-promotion, the title for Play Misty can be spotted on a cinema marquee in Dirty Harry.

The Fan (1981)—not to be confused with De Niro’s The Fan from 1996, though neither are particularly good movies—also explores the dark side of fan obsession. This time, the focus is on a young man who becomes increasingly unhinged in his pursuit of a famous actress, played by Lauren Bacall. The film shares thematic elements with The King of Comedy, particularly in its examination of how celebrity worship can spiral into dangerous, even violent, behavior. Both films depict the breakdown of boundaries between fan and star, culminating in a climactic confrontation that underscores the destructive nature of obsession. The beginning of both movies is very similar.

Other notable—and some not-so-notable—pre-1983 films that look at the dark side of fame, delusion, and obsession include must-sees like A Face in the Crowd, All About Eve, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, and Lenny. On the less remarkable side, there’s The Day of the Locust and Fade to Black.

With a gross of only $2 million on a $19 million budget, The King of Comedy was a box office failure, in part because it was ahead of its time. The film offered a satirical and ironic take on celebrity culture, which clashed with audience expectations. Unlike Scorsese’s earlier works, known for their intense action and drama, this movie focused on uncomfortable, awkward moments that left viewers unsettled.

At the time, there wasn’t a marketing strategy capable of identifying or targeting the right audience for such a film. Executives only knew that it tested poorly everywhere except in New York City, and a few other major cities, leading them to pull the film from theaters after just a few weeks.

However, The King of Comedy is now regarded as a precursor to the “new smart independent cinema” of the 1990s—a genre characterized by sharp social critiques, irony, and a minimalist style. What was misunderstood and poorly marketed in the early ’80s is now recognized as an important milestone in the evolution of independent film.

Years later, De Niro would step into a role reminiscent of Pupkin’s. In 2016, he starred in the dramedy The Comedian as Jackie Burke, an aging comedian struggling to stay relevant in a world that has moved on. While the film didn’t receive much acclaim, it echoed some of the themes from The King of Comedy.

De Niro’s 2019 appearance in Todd Phillips’ Joker marked a more significant return to familiar ground. The film drew numerous parallels with The King of Comedy, exploring similar themes of fame, mental instability, and societal outcasts. De Niro’s role in Joker mirrored Jerry Langford’s character from the earlier film, placing him on the opposite side of the celebrity divide.

Joker is widely recognized as heavily influenced by The King of Comedy, not only in its casting choices but also in its thematic content, tone, and narrative structure. While Joker stands as its own entity, its debt to Scorsese’s 1982 film is undeniable. Some fans have even suggested that Joker verges on homage to The King of Comedy.

Sadly, the box office numbers might have crushed the career of writer Paul Zimmerman, who self-admittedly was a lot like Rupert Pupkin in his desire for fame. He stated, “I’m Rupert Pupkin” “there is a lot of me in him, there is a lot of him in me, I don’t know which comes first by now.” “I went through a classic unhappy childhood really awful awful one and so did Rupert and I’m a dreamer and I live most of my life in the future about things that are going to happen that never do and so does Rupert and I have a real interest in being famous and so does Rupert.” Zimmerman not only envisioned himself as Rupert while writing the screenplay, but he also wanted to be a stand-up comedian. Zimmerman, following the Rupert playbook, minus the kidnapping, did his stand-up on a late-night talk show. [Play Clip] Tragically, Zimmerman passed away just ten years after the premiere of The King of Comedy, never seeing another of his screenplays brought to the big screen.

The King of Comedy may not be a film that offers joy or even traditional entertainment, but it is a film that uses all its talents to their fullest. It’s a movie that captures the zeitgeist of its time, reflecting a society increasingly obsessed with fame at any cost. Scorsese and De Niro, in one of their most daring collaborations, have created a film that is as frustrating as it is fascinating—a bleak yet brilliant portrait of the dark side of the American dream.