Rick Wakeman (Yes) 1999

A never-published interview with Rick Wakeman

In the interview, Wakeman talks about:

- Going on the 700 Club

- Why he did not go out with Yes’s last tour

- How he has never stopped making records

- Being homeless

- Working with independent labels

- Owning up to your own truths

- What he should have done to hold onto his money

- The cost of making his new album

- Working with Ozzy Osbourne

- How Return to the Center of the Earth compares with his new record

- What he learned from King Crimson’s Robert Fripp

- The genre of Art Rock

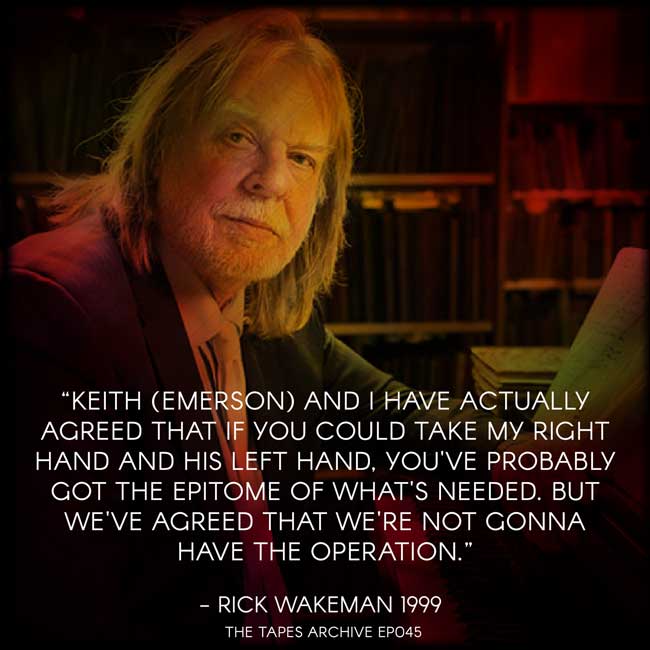

- Who’s better — Keith Emerson or Rick Wakeman

- His upcoming tour with Emerson

- Who would be in his dream band

- The cost of touring in the 90’s

- The cost of touring in the 70’s

- His lows in the 80’s

In this episode, we have one of prog rock’s greatest keyboardists, Rick Wakeman. At the time of this interview in 1999, Wakeman was 50 years old and was promoting his new album, “Return to the Center of Earth.” In the interview, Wakeman talks about being homeless, who’s better — Keith Emerson or him — what he learned from Robert Fripp, and owning up to your own truths.

Rick Wakeman Links:

Watch on Youtube

Rick Wakeman interview transcription:

Marc Allan: I don’t want to start there but before I get to the Center of the Earth I want to ask you a couple of personal things if you don’t mind. I had interviewed Jon Anderson a couple of years ago and he said that you had become “born again” and that you were on the 700 Club renouncing Yes. Is that accurate?

Rick Wakeman: No, it’s complete junk.

Marc Allan: Okay.

Rick Wakeman: First of all, I’m not a born again Christian. I’ve been a Christian since I was five. I’ve on the 700 Club but I haven’t been on the 700 Club for seven years, eight years? Certainly, I mean I’m a fan of Yes. I mean how on earth would I go on? No, I think too many walks in the mushroom fields.

Marc Allan: Okay, well.

Rick Wakeman: That’s complete and utter junk.

Marc Allan: Yeah, I had asked him because you know they went out on the last tour with that Russian keyboard player and he had said that was the reason that you didn’t go on that tour.

Rick Wakeman: I mean the reason I didn’t go on that tour was it was a tour achieving nothing. To me, I mean I’m a fan of the band apart from the times that I’m in it. And to me, that band is a band that needs to be in big venues, putting on spectacular shows. To me the Yes show should be an event. You know, not in sort of, 1,200 seaters. And I felt that we hadn’t got the music. We needed some time to put some real great music together. We’re all playing well but the quality of music wasn’t there that we really needed to do it. It needed Jon, it needed us to actually go back to our roots, and for me that’s where Jon, I mean Jon is so talented coming up with great, sweeping melody ideas and that’s where we should have been sort of starting all the music and that from as we did years ago. Which creates, what I call, “classy ass music”. And I felt that, you know just going around and playing in smaller and smaller venues the time could be better utilized by everybody spending some time you know, trying to gather new ideas working with different people so that when we got back to the table again you know, fresh, we weren’t just sort of decent players but we brought along new things to the table. Because if you just want to go out and play which is fine. I think that the best Yes tour for that, being nostalgic and it was the Union Tour which was just absolutely fantastic. You know, so it really wasn’t you know, my cup of tea. At least not the way that I think it should be done. They’re good lads, and I do love the guys dearly and I wish them lots of luck.

Marc Allan: Okay fair enough. I’ve also read, or I guess I’ve looked this up a little bit, but you’ve been making records. You really never stopped making records have you? I mean, for the last 20 years you’ve basically been recording in England right? Or for the European market.

Rick Wakeman: Yeah, all I did, and a lot of that was by necessity if the truth be known because I mean, I was 50 in a few days time and it’s very easy when you’re 50 to own up to a few things. And there was a period of time in the 80’s which was really difficult for musicians like myself because it was hard to get any formal record contract at all it was hards to get agents to perform. You were persona non grata with young people you were totally out of vogue. It was very difficult. And it wasn’t just me, it was a lot of musicians and people who’d been around in the early 70’s and whatever. Now, for those who’d been sensible and when I say sensible, I mean those who had had one wife who’d stayed in the same band who had the same management who’d listened to their accountants and advisors they’d all managed to put some money to one side so they could ride the storm for a few years and then reappear. I’d made getting married a hobby. I’d been married three times. I had arguments with the tax authorities and lost the court cases so that had bankrupted me, not bankrupted me but basically cleaned me out. The three marriages, very expensive. I’ve been in and out of bands, changed labels and basically I didn’t have a penny. I had absolutely nothing. And in fact, at one stage in the period where I had no, I didn’t even have a roof over my head where I was sort of doing the famous sleeping on the park bench number which is no fun, believe you me.

Marc Allan: You actually slept out? Really?

Rick Wakeman: Yeah, I think it got real, real bad at one stage. And it was very, very, very tough. But basically, then you look around and say, “What can I do, I’ve got to do something.” Can’t get a record, can’t get arrested you know it was… You can get arrested sleeping on a park bench but can’t get arrested making a record you know? So, I then looked around and realized that there was a lot of independent labels starting up all over the place. So I contacted different countries, different labels and said look, what sort of music can you sell that’s like, or are you looking for that’s… You’re not looking for to make current records but something that can go on the shelf that will sell. And for example, Japan, there’s a little independent label I got in touch with, who don’t exist anymore but they were called Jimco and they said, “Oh listen, we would like you. Can you do some rock synthesizer albums?” And I said, “Yeah, what budget you’ve got?” So they had a very, very small budget so I said, “Fine okay, I’ll do something.” Australia, spoke to them, “What do you want?” “Oh we need some quality classical candlelight. That’s what’s doing quite well.” “Great, how much budget can you give me?” Small budget, thank you. So then I went into Germany. They were looking for New Age stuff. I went to all the different territories. And with the money that I’d put together the budget, which was extremely small for all these places I had enough money to put together a decent enough, sort of small studio that I could record them all in. And I worked out that once they’d been delivered then the next small budgets I could actually start making it work a little bit. And so of a period of about four years I produced about 30-odd different CD’s for different markets around the world. And all of them, very, very small budgets. Whilst it kept me alive, and kept me hanging on it didn’t solve the problems that I’d been in and by sort of the early 90’s the tax problems were so huge that I ended up selling all my royalty rights for everything in order to pay the bill. So that was another interesting era because in about ’94, ’93 or ’94 I found myself starting again which was pretty interesting because it pushes you. It’s been an interesting time to put it bluntly. So the reason there’s been a lot of albums was purely a matter of necessity at the time.

Marc Allan: When you’re in that situation, what are you thinking? Because I’m looking, you’re telling me this story and this is the first I’ve ever heard of this and I’m going, if I were in your position I’d be going, “I’m Rick Wakeman. I’m one of the greatest keyboard players ever. Why is this happening?” How did you get through that, how did you deal with that?

Rick Wakeman: Well you do go through, I think, exactly what you said. You do go through the, “I’m feeling extremely sorry for myself.” There’s two things, one of the hardest things is to own up to the truth to yourself. Which is hold on a minute, I’ve screwed up my marriages I’ve not listened to the accountants I’d argued with the tax authorities and lost big time. And really, I’d been fighting the establishment and lost. And when you own up to that, then that’s half the battle. The hardest thing I had to swallow was not the fact that back then I lost everything. The hardest thing to swallow was all the people that I thought were my friends road crew that had worked with me for years that I’d had on retainers and paid really decent money to, just vanished. I couldn’t even get any one of the crew who used to work for me to, even to give me a lift to a railway station. I mean, they disappeared. That was the hardest thing to swallow because people I’d worked with for 10 years who I thought were my friends. That’s when I suddenly realized in this business, I didn’t have any. And I think that was harder to swallow than losing everything.

Marc Allan: Did the guys in Yes know what you were going through?

Rick Wakeman: Um, I don’t know to be honest. I really honestly don’t know. I’ve got a huge sense of pride and it was just, you know, I’m gonna fight my way out of this. And if you want to do that, you do that. And my lovely wife Nina was tremendous. When we met, you know she actually said to me, “This is impossible, the mess you’re in.” She said, “Okay”, she said, “They’ve taken everything else away”, she said, “But they can’t take your talent away.” She said, “You can wave the talent in their faces. Nothing they can do, they can’t have that.” “So go out”, she said, “You’ve done before, do it again.” And it was great, and when you’ve got somebody sort of behind you. And then you start getting the odd break here and there and things start picking up and then you’re sort of steaming away and you know, eventually you sort of you… From the lying down position, you’re on your knees and then you’re sort of half standing up and then you’re standing up and then you start winning again you know?

Marc Allan: So you became like the diagram you always see of man emerging from the water from evolution right?

Rick Wakeman: Well it’s not far off, that, yeah. The older you get though, it is tough. It does take, it takes it’s toll. No doubt about it, it takes it’s toll on you physically. You can do these sort of things when you’re 20 or 30 but it’s a little tricky when you get up to my age now. But I like to look on the positive side of things. For example, if it hadn’t of all been so sour so rotten or whatever would I have pushed myself to do the things that I’m doing now? Or would I have just been sitting back on my laurels going down the golf course every day you know?

Marc Allan: I’ve been a fan of yours, and a fan of Yes and all that since basically I saw the Topographic Oceans Tour. That was one of my first concerts.

Rick Wakeman: Oh all right.

Marc Allan: And to the extent I ever thought about it I always figured that guys like you and the rest of the guys in Yes, and Tull and all those bands would you know, be around for a few years and then they would take their multi-millions and you know, become gentlemen farmers somewhere in England you know? And that was always my vision and what’s happened has been just so, I mean really unbelievable in so many cases.

Rick Wakeman: Well for a lot of people, if you were sensible that’s what you did.

Marc Allan: Right.

Rick Wakeman: I mean, if you stayed with the same band you stay with the same record company you didn’t change lineups, you didn’t change management you didn’t change wives. If you kept things on a stable footing that’s exactly what happens, exactly what you said.

Marc Allan: Are there guys like that who you know who are around you know?

Rick Wakeman: Well the people, sensible people like that like Roger Daltrey, another classic example. The Who, you know obviously when Mooney died that was, obviously that necessitates change. But bands like Zeppelin, no change of lineup. The Who, no change of lineup. Queen, no change of lineup.

Marc Allan: Except that I’ve heard that Entwistle had no money and I’d also heard that Daltrey was not doing great either so that’s-

Rick Wakeman: Well Daltrey, he’s gotten his private enterprises things in the UK. I mean, he has one of the biggest trout farms in the country that’s got to be worth millions and millions. And John Entwistle has, if John just sold his main house in the UK, that could probably solve like half of the crisis.

Marc Allan: Oh okay.

Rick Wakeman: I don’t think those guys are doing too bad.

Marc Allan: All right, so then I’ve heard wrong, okay.

Rick Wakeman: Well it’s not, it might be right and maybe morgie’s up to the hill but I wouldn’t, you know I don’t know.

Marc Allan: Okay, now to Return to The Centre of the Earth. So you must be doing okay now because this must have cost a fortune.

Rick Wakeman: Yeah it was about $800,000 worth.

Marc Allan: Oh my God.

Rick Wakeman: It was not a cheap project to do. This was something I never ever dreamed I would ever get the chance to do. To be brutally honest with you. I mean, again it’s down to money. I mean, I still don’t have any sort of liquid cash. I mean I’ve got a house, a nice house and my studio and things but I don’t have liquid cash anymore. So it’s not something that I could say hey, this is something that I wanted to do therefore I’ll do it. So you’re reliant upon a major record company who looks at something like this and says, “Hey, we see the potential in this. This is something that we think should be done, something we want to do so therefore we will invest in it.”

Marc Allan: Right, but when you made the first one financially, I imagine that people weren’t real concerned and I bet people were kinda, were a little bit more concerned about what it would cost to do this in 1999.

Rick Wakeman: Well that’s right, with the original one I got $35,000 from my endeavor and I did about another 20 myself. So it was about 55 to 60 thousand dollars, the first one cost. And that was recorded live on 16 track of analog and then some mixing in the studio. Which it wasn’t really much to mix because it was all just three mics that hung over top of the orchestra so it wasn’t that difficult to do. Now this time around we’re talking a different ballgame. We’re talking a lot of money a lot of recoupment for a record company and also a lot of understanding from a record company because there was nothing I could play them that could give them a clue as to what it was gonna be like. I couldn’t say well it’s gonna be like this, have a listen to this, this will give you a clue. You almost, I almost sort of shied back from saying “Well one of the things I want to do is get Ozzy Osbourne singing in front of a symphony orchestra.” Because I thought maybe if I say that out too loud it will never get made. Wakeman’s gone to the funny farm. Go on the phone, book him a home in a place in the home for the chronically groovy, he’s gone. I mean I had all these sort of weird and wonderful ideas and things that I wanted to do. But I had to be very, very careful about how I presented them.

Marc Allan: And actually the Ozzy track turns out to be one of the best things on the record I think.

Rick Wakeman: Well I talked to Ozzy about it when I did the Ozzmosis album with him four years ago. I said, “Ozzy do you know, I’d love to do something.” Because the Ozzmosis album was a classic album I thought because Ozzy has almost been typecast by a lot of people as to what styles and things he sings in. He’s a clever boy Ozzy, musically. And Ozzmosis, let me tell you you hear tracks like “Perry Mason” on there, good track. And I said, “You know, I’d love to have you doing something like that, really a fish out of water.” And he said, “What do you mean?” I said, “I’d love to write a sort of metal song for you.” But instead of having all the parts played by the standard instruments that we assume always play the metal stuff you know, the heavy guitars, all the pedals and things I said, “I’d love to have that all done by the string sections.” Like shuffle the pack of cards and say hey guess what, strings you’ve got the guitar part. Hey guess what trombones, you’ve got the bass part. You know, that sort of thing. And I said, “Instead of having all the BVs, backing vocals done by the guy from the band, have it done by a classical choir. But you sing in it exactly as you would.” And he said, “Oh, I’m up for that.” He did a fantastic job. Personally, I think it works and I think it’s a lot of fun.

Marc Allan: Oh yeah, let me tell you some of the things that I really like about this record and then if you don’t mind, I’ll tell you some things that I wish you’d done differently.

Rick Wakeman: Please, absolutely, please do.

Marc Allan: Well some of the things I like, I mean obviously you compare the two records and I don’t think, I mean I’ve had 25 years with the first one, and two weeks with this one so it’s not really fair. But one of the best things is you know, you got great singers. And the guys who sang on the first one were marginal at best singers, I would say. Yeah, I wonder if in looking back on the first one if you thought that gee, that vocals could have been one thing that would have been improved.

Rick Wakeman: Yeah, I think that’s not a bad analogy. The first one was difficult because I had the choice of do I get guest singers in but there’s really only four songs? Do I get guest singers in and feature, and do what they did with the orchestral versions of “Tommy” which is you know, and then you suddenly fill it full of guests. Or do you go the other route and have everybody on the stage completely unknown? So the focus then goes onto the music. And I think there’s very valid arguments to both ways, and I’m not really sure what the utopia would be. But certainly, when we came to do this one this was an area where I wrote songs specifically for singers. I think it’s valid, what you say.

Marc Allan: Yeah, another thing that I like about this is that your playing is more expansive. There are parts of this where I say, “Wow”. The first album I think, it really clings together as a symphonic thought, you know as a whole piece. This is like a dream to hear Rick Wakeman playing like this again.

Rick Wakeman: There’s totally different thinking for this one. I mean, you are right. And there was an element of the old Robert Fripp thinking in this. When you’re 23, 24, 25 years old the word, “silence”, when you’re playing in other words, don’t play here is something that is not in your vocabulary. You’ll play something even it’s not right or the wrong instrument. Just because you want to be playing. You don’t want to be seen doing nothing. Robert Fripp, I did a few sessions with Fripp back in the 70’s. And one of the things that Robert does I remember doing one session with him and he didn’t play for about two minutes. And I said, “Are you gonna do something here?” And he said, “No”. And I said, “Why not?” He said, “Because there isn’t anything for me to play.” And he said, “I shall play in that little section coming up there, then nothing there then there, there, and there, and there.” Now what was amazing, when I listened back to the track that we did then, all that seemed to stick out was what Robert had did. And I certainly said, he said, “That’s because I’ve got six entries and six exits.” He said if you only have one entry and exit he said it loses the track. He said, “And if I want to play an important part” he said, “Then I play when necessary and play the sound of the things when necessary.” And that’s something that I have to say I’ve tried to do much more of in recent years. And certainly with this album. All the keyboard solos for example none of them went down until everything else had been recorded.

Marc Allan: So you knew when to put in your entrances and exits.

Rick Wakeman: Exactly.

Marc Allan: Yes, perfect.

Rick Wakeman: Yeah, yeah, exactly.

Marc Allan: That’s great, and now the thing that I wish you had done differently is I wish this were shorter. And I don’t wish it were shorter because there’s stuff that shouldn’t be on here.

Rick Wakeman: Right.

Marc Allan: You’re 50, or you’re going to be 50. I just turned 40, and I listen to… I can’t tell you the last time I had an hour and 15 minutes to listen to something. And you know I have two little kids in the house and it’s just chaos all the time and it’s very hard to sit down. And I go, God you know, I just said that’s I guess the beauty of the first one is I wish there were more.

Rick Wakeman: It’s 36 minutes long.

Marc Allan: 36 minutes.

Rick Wakeman: Yeah, well I’ll tell you the original demo runs to 125 minutes. Now, I knew that it was always gonna come down from there because of course the narration is overblown. A lot of the things are overblown so you’re continually editing and editing and editing and editing and editing to bring it down till it sounds tight. It was always going to end up as where it was gonna end up and it ended up at 70, or was it 76.50 or something quite right. You know I too have kids running around the house and I can sympathize there.

Marc Allan: Yeah, I’m enjoying this. I like you know, that era of music is… Nobody’s really ever gone back and done that and I think that’s the best era of music there was. People can make fun of you know, art rock or whatever they want to call it all they want but I mean, you had the best players playing some of the most inventive, interesting music of all time.

Rick Wakeman: Yeah, it was interesting you picked up on the singers. I looked at the same juncture of do I get you know, some of my friends some of the classic players and the instrumentalists to play the band parts? And I ended up using a band where the guitarist is 24 the drummer’s 23, and the bass player is 23. And it was really incredible because these guys, they’re great players. And they, second one you said, they said we love that era, and we know it got knocked by people in the art rock scene a bit. But what a great time for musicians. What a great time to be able to play. So that’s a lot of people say to well, people who don’t like art rock or classical rock orchestral rock, call it what you like. They’ll say the problem is it’s all contrived. You try saying that to the musicians that play it because the first, they’ll turn around to you and say “We’ve never had so much freedom to show any ability or what we can do. There’s no other music that allows us to do this.” Art rock is a genre of music that in general people either love, or they hate. I mean for example, reviews for this album in the UK where you know, it’s been good. 70% of them have been fantastic. But we’ve had another percentage of about 20% where it’s from people who just can’t stand the orchestral rock. Have never been able to stand it and would dearly like to take me to one of the entrances to the center of the earth drop me down it, and then close the entrance up. And unlike any other type of music they suddenly become really opinionated because they’ll say, “Ah, this is fantastic. I’m so glad something like this has happened. This is absolutely wonderful, this is great music.” And just go off into a euphoria that’s almost embarrassing. And then they’ll say this, then two down the line you can read a guy, you know “Why doesn’t somebody assassinate Wakeman?” “Why don’t they just open up the center of the earth and drop him in it?” You know, and it’s, because some may say it makes it, but it also makes it interesting. It’s interesting that in that era of the 70’s as well we were all, whether we were fans of one type of music or not we were all passionate about our music. And it’s interesting that this type of music does bring the passion back. One way or another you know.

Marc Allan: When I was in high school and listening to Listen I would listen to it, we would have arguments. You talk about passion, arguing every day about who’s better, Rick Wakeman or Keith Emerson? Who’s better, you know, Steve Howard, Jimmy Page. Stuff like that.

Rick Wakeman: I can solve the first one for you because Keith and I have been great friends for years, and years, and years. And we always thought it was a lot of fun that these things kept coming up in newspapers, who’s best. Because the interesting thing is we are two totally different styles of players. In every respect. I mean, Keith and I have actually agreed that if you could take my right hand and his left hand you’ve probably got the epitome of what’s needed. But we’ve agreed that we’re not gonna have the operation. What we are gonna do, we’re gonna do a tour together next year instead.

Marc Allan: Really?

Rick Wakeman: Yeah, I mean we’ve been working on this now for about six months. So we’re gonna go out and we’re gonna put together… This is not where he’s on stage for a bit and I’m on stage. It’s where we’re working together solidly for an evening.

Marc Allan: And what are you gonna do? I mean, will you have a band with you?

Rick Wakeman: Oh yeah we’ll have a band, we may even have an orchestra. We’re past the embryo stage, it’s now… Keith and I have been quietly working on this now for about four or five months.

Marc Allan: Are you gonna bring that to the US?

Rick Wakeman: It’s gonna be in the US, that’s where it will start. So that’s gonna be a lot of fun.

Marc Allan: From all the players that you’ve played with and all the players that you know of is there a Rick Wakeman dream band? Could you put one together?

Rick Wakeman: Gosh a dream band. There’s a few people I’d like to play with who I never have played with, I must admit. I mean, I would love to do something with McCartney. Just to do, even if it’s just to sit up on stage and play something. There’s so many great musicians around. I would like to see, I had a great time in the session days when I was going around playing on loads of people’s sessions. It was just great fun. I do enjoy working on other people’s music and I enjoy working with other people. Dream band, I mean a lot of the guys I always dreamed of playing with or wanted to play with, I’ve done. I had people like Brain May I’ve worked with Steve Howard. Joe Satriani was great fun. I’ve been extraordinarily lucky. Perhaps on a band side of things there are two bands I would have loved to have worked with, who didn’t have keyboard players. Who I would have jumped at the chance to have become the keyboard player of those bands. One was The Who, and the other one was Zeppelin. If those two bands had decided that they’d wanted a keyboard player I would have put in my application. I’d have filled in the form and sent off the CV.

Marc Allan: Are you gonna tour with The Return?

Rick Wakeman: Yeah, very much so, I want to. It’s a bit frustrating at the moment. It’s gonna cost an arm and a leg to put this on as you can appreciate.

Marc Allan: Oh yeah.

Rick Wakeman: So it will need sponsorship and all the things along that go with it. We’ve got sponsors and people standing by who have really wanted to get involved and do it but they’re all just waiting, quite rightly so to see how the album is received. If it’s received well and does okay then there’s no doubt about it they’ll press the green light and away we’ll go. But of course, their argument’s gonna be if it doesn’t do what people hope they’re gonna say, “Well look why should we invest in a show, where’s the audience gonna come from?” But we know we can make the show really work because all the major cities around the world have got great symphony orchestras and choirs. It’s not that difficult to actually stage it and do it. The difficulty is finding the underwriters and the sponsors. And they’re only gonna come forward once we know how the album’s actually doing. And that’s probably gonna be I would think decisions will start to be made around about the end of June.

Marc Allan: Isn’t it amazing to you how much business plays a part in music anymore?

Rick Wakeman: It’s sad.

Marc Allan: Yeah.

Rick Wakeman: It’s very sad, and what’s frustrating for me was back in the 70’s the money that I had from the records I didn’t have, there were no such thing as sponsors. They weren’t there. And when I did the original Journey tour in America I lost a quarter of a million dollars. We sold out everywhere, we sold out all 18 shows but it lost a quarter of a million dollars. Which is a fortune now, can you imagine what it was back then? But I had made a quarter of a million dollars on the sales of the record. So I put all the money back in to do the tour knowing that it would lose the money. And I didn’t have to, the manager said to me, “Oh you’re mad, you’re crazy to do this. You know you can’t do it.” I thought okay, it’s my money I’ll do what I like with it. I want to go out on tour, I want to take an orchestra so I’m gonna do it. If I was in the position today where I had some money in the bank and I could afford to go out and spend it all I’d put this on the road without having to talk to people. I would do it, but you’re dead right. It’s turned into a business now where you’re reliant upon other people and it is the business side of things that takes priority.

Marc Allan: Are you glad you made your mark in music when you made it?

Rick Wakeman: I wouldn’t change one iota of the era that I’d come through. There’s nothing more fantastic than to come through a pioneering stage. And I came through the stage where keyboards were being pioneered and I was allowed to get involved in the development of keyboards. The same with recording, and technology. In the 30 years I’ve been doing it since I left college I mean, I’ve had some fantastic highs and some stunning lows. And I suppose that that’s something you should expect in this business.

Marc Allan: Is there anything else that you want me to tell people about what you’re up to? Anything you wanted to talk about that we haven’t gotten to yet?

Rick Wakeman: I think we’ve just about covered everything. Basically the next 8-10 months is gonna be heavily taken up with Return and then it’s gonna be moving hopefully into putting the Emerson/WAkeman tour together. Which I’m looking forward to very much. And then after that, I mean that’s gonna when you think about it that’s gonna go through 2000, into 2001. I don’t know what will happen particularly after that. I mean, I’ve had a few health problems over the last year so there’s gonna come a time when I’m gonna have to quiet down a bit. And so it might be just after I’ve done the project with Keith. It might just be time to sort of hold back a little bit.

Marc Allan: What’s been wrong if you don’t mind my asking?

Rick Wakeman: Last year I had a bad time. I had chronic pneumonia and pleurisy and a form of legionnaire. I actually was, they only gave me 48 hours at one time. I was a pretty sick boy. Sort of went into the hospital weighing 220 pound and came out weighing 180, you know.

Marc Allan: Wow.

Rick Wakeman: I’ve damaged my right lung and a few other areas. And I have to, I can’t do the things that I used to do and they sort of wagged their finger at me and told me that things have to change. They basically said if I had another attack like it I won’t come out of that one. So I’ve got to start looking a little bit more sensibly. So I’m aware that maybe in two or three years time I’m gonna have to maybe look more toward the continual writing side of things maybe to move it more to the era of writing and doing movie music, kind of whatever. Which doesn’t put the same pressures on of continual traveling and you know, inventorying of things that I’m doing at the moment.

Marc Allan: One other just housekeeping matter and that is when you were talking about your lowest lows. What years are we talking about there?

Rick Wakeman: What the lows?

Marc Allan: Is it the 80’s, yeah.

Rick Wakeman: Yeah, the lows I suppose, probably 1980 was the year that really stank for me because my second marriage collapsed. I lost everything, it was the start of the whole punk movement. Which you know, that’s fine, but it just destroyed me. I was hitting a bad way, I then lost. I was losing a lot of big tax cases. I lost everything that I had in the second divorce. And then my father died. And that was the bad icing on the cake because it was like, well what else can God throw at me you know? And that was pretty tough. And then I went through a period of feeling extraordinarily sorry for myself for about six months to a year. Where I really felt sorry for myself and I felt that everybody else in the world was to blame but me. It is true that the situations that I found myself in was not totally of my own doing but the fact of life is that at the end of the day you know, you do have certain control over your destiny. And you can shape things. If you want to sit there and be bloody miserable then that’s fine, but it aint gonna get you anywhere. You know, not having a roof over my head was a real low. I mean that was because you just wonder where you’re gonna go from there.

Marc Allan: That was in ’80 or ’81?

Rick Wakeman: Yeah.

Marc Allan: Yeah, oh man. Well listen, I appreciate all your time and I wish you the best. You and your music have given me a lot of joy throughout my life.

Rick Wakeman: That’s very kind, thank you sir.

Marc Allan: And I hope that things work out well for you Rick.

Rick Wakeman: That’s very, very kind, thank you very much.

Marc Allan: You take care of yourself and I hope to see you here.

Rick Wakeman: That would be lovely, please. That would be wonderful.

Marc Allan: Okay you take care.

Rick Wakeman: Thanks a lot.

Marc Allan: Buh-bye.

Rick Wakeman: Bye