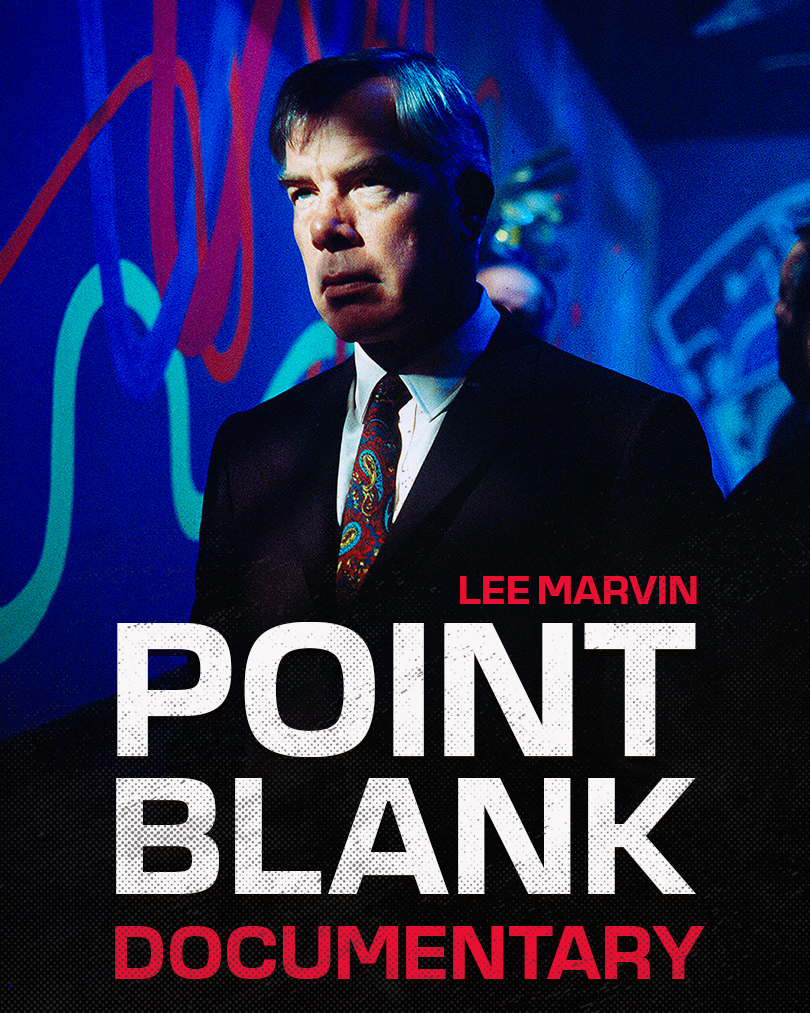

Point Blank (1967) | The Documentary

Learn something new about the classic crime thriller, “Point Blank”(1967), starring Lee Marvin. This full-length documentary uncovers never-published information via John Boorman and 4 months of research. No other book, podcast, or video has taken this deep of dive on the film “Point Blank.”

“Point Blank” is a 1967 American neo-noir crime film directed by John Boorman and starring Lee Marvin, Angie Dickinson, Keenan Wynn, and Carroll O’Connor. The screenplay, written by Alexander Jacobs, David Newhouse, and Rafe Newhouse, is based on the 1963 novel “The Hunter” by Donald E. Westlake (published under the pseudonym Richard Stark).

The film follows Walker (played by Lee Marvin), a stoic and relentless thief who is double-crossed and left for dead by his partner, Mal Reese (played by John Vernon), and his wife, Lynne (played by Sharon Acker), after a heist on Alcatraz Island. Walker survives and embarks on a quest for revenge, seeking to recover the $93,000 that was stolen from him. His journey leads him into a complex web of betrayals and deceit, navigating through the criminal underworld and a shadowy organization known as “the Organization.”

00:00 – Intro

00:13 – Lee Marvin is wounded in WW2

01:07 – Director of Point Blank John Boorman

01:42 – DW Griffith’s influence on John Boorman

02:30 – How Point Blank got made into a film

03:28 – Why Lee Marvin took the role of Walker

04:28 – How John Boorman connected with Lee Marvin

05:22 – Lee Marvin had absolute control of Point Blank

05:43 – John Boorman brings on a writing partner

06:30 – Boorman’s vision for Point Blank

07:47 – The Production Code tries to rewrite Point Blank

10:30 – Angie Dickinson gets the co-starring role

10:58 – Angie Dickinson was not upset with Lee Marvin

12:01 – Vivien Leigh beats the crud out of Marvin

12:21 – Keenan Wynn is cast as Yost

12:51 – Carroll O’Connor is cast

13:19 – Lloyd Bochner is casted

13:58 – John Vernon and Sharon Acker are added to the cast

14:46 – James Sikking is added

15:09 – The color of Point Blank

17:04 – The cinematography of Point Blank

17:25 – Cinematographer Philip H. Lathrop

18:21 – The orginal film location for Point Blank

18:52 – Movie making on Alcatraz Island

19:53 – Lee Marvin gets drunk with Ella Fitzgerald

20:13 – Sharon Acker gets shot and goes to the hospital

20:32 – Lee Marvin, does his own stunts

20:51 – Walker is coming to get you

21:49 – Lee Marvin does more than act in Point Blank

24:02 – Homosexual overtones in Point Blank

25:21 – How The Beatles and Drew Barrymore are connected to Point Blank

26:43 – Point Blank does a Hollywood first

28:04 – Tragic ending a year later for Brewster’s plane

28:39 – Dad joke

29:04 – Was Walker alive or dead?

32:25 – Editing Point Blank

33:01 – A joke for the video editors

33:42 – The music of Point Blank

34:48 – Point Blank premieres

35:01 – Point Blank fashion shoot

35:26 – Box office for Point Blank

36:22 – Point Blank movie survey

36:59 – What the movie critics thought of Point Blank

38:58 – What we think of Point Blank today

39:11 – Martin Scorsese on Point Blank

39:48 – Christopher Nolan on Point Blank

40:29 – Reservoir Dogs, Point Blank and Tarantino

41:04 – Hell in the Pacific

41:42 – Winkler and Chartoff sucess

42:24 – Point Blank summary and outro

Interview with Point Blank co-writer Alex Jacobs

Click here to read it. Excerpt from Film Quarterly Winter 1968-1969.

Point Blank script:

On June 18, 1944, Lee Marvin and the 24th Marines, Fourth Division, faced a devastating ambush in the South Pacific, with shellfire from Japanese forces drastically reducing their numbers from two hundred and forty-seven to six. Marvin himself sustained a severe injury from machine gun fire, resulting in a critical wound to his lower back. After participating in assaults on 21 enemy-held beaches over six months, his active combat ended, leaving him haunted by the loss of his comrades, plagued by nightmares, and self-medicating with alcohol.

He carried the survivor’s guilt from the ambush that mostly annihilated his platoon. This internal conflict became a driving force behind his intense and compelling performances on screen. Point Blank begins with a man shot. Lee knew how to play a man back from the dead.

“Lee Marvin, was always Lee Marvin, a drunk recovering from the trauma of war.” John Boorman

Marvin quote: I don’t take pledges; I quit drinking every morning, and I start again every evening.”

Sir John Boorman, the director of “Point Blank,” initiated his career in the film industry as an editor before transitioning to directing documentaries and television projects for the BBC. This path led him to his debut feature film, “Catch Us If You Can” (1965), a venture inspired by the success of The Beatles’ “A Hard Day’s Night,” featuring the pop group The Dave Clark Five. While the film did not achieve significant commercial success, it garnered critical acclaim, contributing to Boorman’s emerging reputation in the film industry.

[onscreen text]

“It is one of those films that linger in the memory” Pauline Kael The New Yorker

“if Catch Us If You Can “isn’t the best pop-as-art film, it is definitely the most poignant” Howard Hampton

Boorman’s last documentary with the BBC, titled “The Great Director,” focused on the pioneer of narrative filmmaking, D.W. Griffith. Spending over a year on this project, Boorman gained a profound understanding of Griffith’s contributions to cinema. He openly acknowledged Griffith’s immense, yet often unrecognized, influence on filmmakers and the film industry, stating that all filmmakers are greatly indebted to him, even though many in the industry and general audience are unaware of the extent of this influence.

Boorman’s accumulated experience and insight, particularly his deep comprehension of cinematic history and narrative techniques, were instrumental in authentically portraying the anguish and complexity of Lee Marvin’s character on the screen.

Through Nat Cohen, the producer of “Catch Us If You Can,” John Boorman connected with American agents-turned-producers Bob Chartoff, Irwin Winkler, and Judd Bernard. This group had just finished their first film with MGM, “Double Trouble,” starring Elvis Presley, and were searching for a new project.

The pathway to their next film emerged through Patricia Casey, Bernard’s assistant, who was acquainted with film editor David Newhouse. Newhouse and his brother Rafe had secured the rights to “The Hunter,” a crime thriller by Richard Stark, a pen name for author Donald E. Westlake, and had developed a screenplay from it.

Casey introduced the screenplay to Bernard, who then discussed it with Chartoff and Winkler. The trio quickly recognized the story’s potential and purchased the screenplay rights from the Newhouse brothers. Part of the agreement with the original author, Westlake, was that the movie and main characters’ names would need to be changed. The Hunter turned into Point Blank, and the main character, Parker, would be altered to Walker. Westlake, who had published eight books featuring Parker by 1966, only permitted using the original name if it was for a series. In a humorous nod in his 1967 book “The Green Eagle Score,” Westlake included a reference: “the other one had called him by a different name, which Berridge could no longer be sure he remembered. Porter, Walker, Archer…something like that.”

The producers were in agreement that Lee Marvin, who had recently won an Oscar, would be perfectly cast as Walker. Bernard recalled, “Marvin said he was interested. Six months went by, and nothing happened. I couldn’t get the picture off the ground. Then something clicked. Every actor had turned it down. Alex Cord, Tony Curtis, Stuart Whitman, Peter Falk.”

What clicked was a bit of a farce. While Bernard was in London, according to the director Sidney J. Furie, Bernard screened Furie’s movie The Ipcress File (1965) for Marvin and convinced him Boorman had directed it. Marvin, liking the movie, agreed to meet with Boorman to discuss the project. Marvin was in London filming The Dirty Dozen(1966). Boorman was under the impression Lee had never seen any of his work.

When Marvin and Boorman first met, they both admitted they didn’t like the script but liked the Walker character. They both felt his quest for revenge had potential. After meeting a couple more times, Boorman understood more about Marvin’s war experience; he came to realize that Marvin was completely brutalized by the war and that, in a way, acting for him was a way to recover his humanity or to purge himself of what he’d done. This understanding influenced Boorman’s approach to rewriting the script.

Boorman told Marvin he felt Walker was emotionally and physically wounded to a point where he was no longer human, making him frightening but also pure, in a certain sense. His only connection with life was through violence, yet he lacked the conviction or cruelty or passion to take pleasure from it or satisfaction from vengeance. Boorman painted a bleak picture, and Lee was intrigued.

“Lee looked at me in the eye and said, ‘I’ll do this flick with you, on one condition.’ ‘What’s that?’He tossed the script out of the open window.”

[onscreen text] Excerpt From Adventures of a Suburban Boy John Boorman

Production:

Lee Marvin had script approval, cast approval, and approval of key crew in his contract. He told all the bigwigs at MGM that he deferred the approval to John. So, on his first Hollywood-backed feature film, Boorman had almost total control of his movie.

Script:

With a budget of $2 million, Boorman, now tasked with a complete overhaul of the screenplay, reached out to Alex Jacobs, an old associate from their BBC days. Together, they embarked on an intricate yet expedited process of redrafting. With each new version, they further streamlined the dialogue. The original script had an old-fashioned, throwback gangster feel, whereas Jacobs and Boorman wanted to make an enterprising, fresh thriller that was a half-reel ahead of the audience. The script is anything but conventional and is presented in a series of fragmented, non-linear, deliberately dream-like scenes that make it quite unlike any American crime film that came before it. Boorman’s vision was to reshape the gangster genre, maintaining its inherent violence while crafting a complex narrative structure.

Boorman felt the character Walker represents an average person, isolated and unsupported, grappling with the might of a corporate entity, only to face constant dismissal and marginalization. His response to this rejection mirrors the path of violence, like the fictional character portrayed by Michael Douglas in “Falling Down” or the real Tony Kiritsis in the documentary “Dead Man’s Line.” This narrative highlights the elite’s indifference towards the growing resentment and frustration among ordinary people. The Organization’s bosses all react to Walker as if his bold rage is not allowed or justified.

The suggestive rather than explicit script made no sense to MGM president Robert O’Brien, but with Marvin’s approval deferral to Boorman, there wasn’t much he could do about it. MGM’s Timing department did call Boorman in because the script only clocked in at 71 minutes. Boorman explained their estimate did not consider the number of pauses and silences in the film or the short flashbacks to previous ones(some reshot in slow motion). This would add up to another 31 minutes, totaling a 92-minute movie.

Boorman later stated, “I knew that the script wasn’t right; there were problems desperately wrong with it, basic flaws, which I tried to cover up, paper over, never quite succeeded in doing so.”

Writing a script in 1966 could be quite the challenge; not only did you need to please your stakeholders, but you also needed to appease the Production Code Administration by adhering to the Motion Picture Code.

Production Code:

The Motion Picture Production Code, commonly called the Hays Code, represented a set of self-imposed guidelines for content censorship in American motion pictures. Most major U.S. film studios actively adhered to this Code from 1934 until 1968.

In 1966, upon assuming the presidency of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), Jack Valenti encountered his first challenge with the film “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” over its explicit language. Valenti brokered a deal that saw the removal of the word “screw” while retaining other controversial phrases, such as “hump the hostess.” The film ultimately gained approval from the Production Code despite including previously banned language. This incident prompted a revision of the Code, reducing the number of explicit prohibitions but introducing a new power for the Production Code Administration to designate films as “suggested for mature audiences.”

While Boorman was writing the script, the Hays Code was on its last legs, yet it was still trying and succeeding in censoring “Point Blank.”

Between October 1966 and February 1967, the Production Code Administration or PCA sent several letters regarding their concerns with the script. Such as:

“This stomping and kicking seems excessively brutal and we ask that it be eliminated.”

“We ask that you shorten the dialogue referring to Mall’s past behavior with prostitutes.”

“With the change in the character of Yost, from a Justice Department official to a top criminal, the story now has a flavor of unrelieved criminality.”

“The business of pushing the gun in Brewster’s mouth is unacceptable.”

“It will be essential to avoid unacceptable nudity or vulgar dancing.”

In early January 1967, the PCA threatened to basically blacklist the film by not approving it at all.

“We note several important changes in this script from the previous version submitted for Code consideration. In our opinion, these revisions produce a script which now includes extremely serious problems under the Code and one which would result in a film that could not be approved by this office.”

After several script changes, the PCA would approve Point Blank with a rating of “Suggested for Mature Audiences.”

While “Point Blank” was technically made and released under the Hays Code, it was part of the movement that helped end the Code’s dominance. The film’s style and content reflected the changing attitudes in American cinema and society, contributing to the shift towards more mature and complex film narratives.

Cast:

Boorman chose Angie Dickinson over Stella Stevens, MGM’s choice, for the co-starring role of Chris. Marvin had worked with Dickinson in “The Killers” (1964) and M Squad (1957). Contrary to popular belief, Dickinson did not hold a grudge against Marvin for the scene in “The Killers,” where Marvin hung her out of a window. Yes, Boorman alluded to it in a couple of interviews in jest. But think about it. Why would Dickinson be upset about a scripted stunt done on a TV set? There was zero danger to her. Was she mad at Ronald Reagan for slapping her in the face? Dickinson’s intense performance in the slapping scene with Marvin was her following the script, not personal animosity. Behind-the-scenes images show the cast smiling after shooting the scene, and Dickinson’s comments about Marvin were always positive, describing him as “a tough bastard. And a great guy,” and “a man of few words. He was pretty awesome.” While Marvin preferred Peggy Lee, his co-star in “Pete Kelly’s Blues” (1955), he was content with Dickinson’s casting.

Speaking of Marvin getting slapped around, actress Vivien Leigh took it to Marvin with her high heels two years earlier.

To play the part of the mythical Yost character, Marvin personally chose Keenan Wynn. Wynn and Marvin developed a lifelong friendship during the production of “Shack Out on 101” in 1955.

Four years before his renowned role as Archie Bunker in “All in the Family,” Carroll O’Connor secured the role of Brewster. Boorman recalled an incident during the shooting of O’Connor’s death scene. They discovered in the dailies that O’Connor made absurd sounds that caused laughter. When O’Connor was already on his way back to LA, they had the Highway Patrol intercept him to return for a reshoot, much to his chagrin.

Boorman initially wanted blue-eyed villains, intentionally avoiding casting Italian or Jewish actors. Yet, he learned after casting Lloyd Bochner as Frederick Carter that Bochner was Jewish and devoutly religious, contrary to his casting intent. By 1968, he still had not realized this discrepancy. Did the Organization have the mysterious overtones?

“I wanted to make it the business world. It seems to me the business world is the Organization in America. I didn’t have any Jews or Italians in it; they were all WASPS, everybody had blue eyes.”

John Vernon and Sharon Acker, notable for their strong performances in the Canadian TV series “Wojeck,” made their Hollywood debut in these roles.

Marvin, doubting Vernon’s ability to match his intensity, heightened tensions during rehearsals at his house. While rehearsing, Marvin punched Vernon in the stomach, causing him to double over in pain and cry, asserting he’s an actor, not a fighter. Boorman noted Marvin’s intoxication during this incident.

Vernon later appeared in major films like “Dirty Harry,” “The Outlaw Josey Wales,” “Animal House,” and others.

James Sikking, eager to play the assassin, faced initial rejection by Boorman for looking too nice. Undeterred, Sikking frequently waited outside Boorman’s office, hiding like an assassin, to demonstrate his suitability for the role. This persistence paid off, and Boorman cast him.

Color

Boorman considered filming “Point Blank” in black and white, but the prevailing Hollywood strategy at the time was to make movies in color to compete with the growing television market. As “Point Blank” was Boorman’s first color film, he embraced creativity. He shot each scene emphasizing a single color, progressing from greys and blues to dark red in the final acts. For example, Carter’s office is entirely composed of shades of green, the entrance, blinds, carpet, phone, walls, and the actors’ suits. Green symbolized who had Walker’s money, which lent a unifying power to the scenes.

The MGM art department head didn’t initially grasp this vision. Boorman explained that the green tones would vary: some would appear yellowish due to the film’s emulsion reaction, while others would lean towards brown. Ultimately, Boorman’s concept proved successful. The color variation was notable: Stegman’s shirt remained green, but his suit appeared blue, Carter’s attire looked grey, and other clothing items showed brownish tones. This color diversity highlighted Boorman’s unique approach effectively.

In another example, Lynne’s apartment showcases a palette of silver, grays, and metallic blues, which creates a cold, sterile atmosphere. In contrast, her sister’s house exudes warmth with its yellow and orange hues. Boorman, adhering to his color scheme, also injected creativity into it. For instance, he painted a coin-operated telescope yellow to complement Chris’s dress and Walker’s slightly darker shirt and tie.

Boorman would later confess that Dickinson “was very unhappy with me about forcing her to change her hair color. I had this maniacal idea that I wanted her hair to be the same color as her dress, and we went through three dyeing jobs to get there. The hairdresser at MGM said, ‘I can’t go any further, her hair’s starting to break off.’”

The film’s meticulous color planning even extended to the city’s rented weather and mail helicopters. Aligning with the progression through the color spectrum, the crew painted the opening scene’s whirlybird grey while they colored the final scene’s helicopter red.

This innovative approach to using color for storytelling and evoking emotions was groundbreaking. In later years, directors like Tim Burton would advance these ideas even further. Today, film credits often include a specialized role to enhance colors digitally, known as “Colorist.”

Cameraman:

“Point Blank” stands out for its distinctive cinematography, partly due to Boorman being the first filmmaker to use the newly created Panavision C Series Anamorphic 40mm lens. This lens allowed the creation of wide and distinctive visuals. Boorman described himself as “intoxicated by anamorphic.” Additionally, the film benefited from the expertise of cinematographer Philip H. Lathrop, who was Oscar-nominated for The Americanization of Emily (1964) and his renowned work on the iconic twelve-minute opening shot in Orson Welles’s “Touch of Evil” (1958). Lathrop’s experience in black-and-white noir was pivotal in capturing Boorman’s color noir vision.

Lathrop significantly aided Boorman in transitioning to working with a major studio while fostering his creative instincts. Boorman remembers a specific instance reflecting this dynamic. At that time, the cumbersome studio Mitchell camera was commonly used in American filmmaking, but ‘Point Blank’ was also being shot with the smaller, more agile Arriflex. Lathrop, aware of the studio executives’ visit to the set, advised Boorman to use the big camera while they were around. ‘If they see all that money disappearing into that itsy-bitsy camera, they’re going to get very nervous.’

The original screenplay had the location as San Francisco. Once Boorman saw San Francisco, he felt the gentle hills and pastel colors were wrong for the bleak, cold picture he wanted to make. So, he moved the bulk of the shooting to Los Angeles. At first, the studio did not like the change, but once they figured shooting in LA over San Francisco would save them $100k, they were all for it.

Filming began on February 20, 1967 and lasted eight weeks.

Alcatraz:

Although Boorman shot most of “Point Blank” in Los Angeles, he filmed the opening scene at Alcatraz Island, making it the first motion picture filmed at the former federal prison.

Money and bipartisan political persuasion made it possible to convert Alcatraz into a movie set temporarily. Producer Judd Bernard worked with Republican Senator George Murphy, San Francisco Democrat Mayor John F. Shelley, and the President of the Motion Picture Association Jack Valenti to make it happen. MGM accepted any liability for accidents, paid $2,000 a day in rent, and agreed not to glamorize any former inmates like Al Capone or Machine Gun Kelly.

For the two-week shoot at Alcatraz and Fort Point, the production needed to be self-contained, which necessitated the installation of its own electrical and water plants, toilets, and commissary facilities. MGM would send six 10-ton trucks, five trailers, two moving vans, and 11 standard trucks carrying 28 10,000-watt lamps, 55 at 5,000 amps each, two generators of 1,400 amp power, five at 1,000 each, 15 electrical spotlights, four self-contained generators, ten dressing rooms, a complete make-up unit with one dozen hair dryers and shampoo tables, plus an assortment of furniture and miscellaneous items to maintain a company of 125 on the island. The equipment was transported from the San Francisco mainland by a studio-leased barge.

On the first day of shooting, Lee Marvin was nowhere to be found. Upon arriving in San Francisco the night before, he and Jazz legend and co-star from Pete Kelly’s Blues (1955), Ella Fitzgerald, went on an all-night bender. Boorman, infuriated, destroyed his hotel room.

In the scene where Vernon’s character shoots Walker, Actor Sharon Acker’s right forefinger floated past the gun’s nuzzle. The powder blast from the blank ripped open the inside of her finger. Eight stitches were required. Acker was in shock for 2 hours and remained hospitalized for the better part of the day.

When it came time for Marvin’s stuntman to swim off Alcatraz, the stuntman said it was too cold. So Marvin did it himself. Since Marvin did this and other stunts, he was awarded a bonus “stuntman” check at the movie’s wrap-up party.

Walker is coming to get you:

The “Walker’s coming to get you” scene in “Point Blank” is the film’s most discussed segment. Featuring Walker, who has returned from the dead seeking his money, the crew shot this scene in Terminal 6 at the Los Angeles International Airport, built in 1961. It wasn’t the first movie to use the backdrop; “Smog” (1962) was the first, followed by “Sunday in New York” (1963) and then “The Loved One” (1965). And Point Blank would not be the last movie to use this vibrant backdrop. [Show montage.]

For years, people mistakenly credited Charles Kratka for the beautiful tilework you see behind Walker as he strides through the airport, when Janet Bennett, his contractor, created it. Kratka assigned her the task of designing a mural to divert attention from the length of the tunnels. In the 2007 L.A. Times obituary, Kratka’s children mentioned that he described the mural’s changing colors as reflecting the changing seasons. However, Bennett revealed her true concept: representing the changing terrain seen during a transcontinental flight “from ocean to ocean.” Bennett only learned about Kratka claiming the mural as his own after reading his obituary in 2007.

During the sequence, you see Walker, the executioner, as he marches through the deserted airport corridor on his way to his wife, who betrayed him. The shots intercut with her putting on make-up and in the beauty parlor to symbolize her being anointed and embalmed for death.

Following Marvin’s death, his widow offered Boorman the chance to select a keepsake of Lee’s. Boorman chose the size 13 shoes Marvin wore in that scene, which are now preserved in the Boorman Archive at the University of Indiana.

It was Lee’s idea to shoot into the empty bed of the wife who had betrayed him. Marvin chose a Smith and Wesson 45 Magnum, renowned for its large size in the handgun category. It is the same type, except with a longer barrel, later made famous by Clint Eastwood in Dirty Harry. Marvin planned to dramatically portray the recoil, making his arm jerk backward, even though the gun was loaded with blanks and had no actual recoil. This exaggerated action served as a metaphor, illustrating the ironic backfire of his character’s pursuit of revenge. –Sidenote: When they shot actual live rounds on Alcatraz island, there was no recoil at all.

Boorman stated that Marvin was “a huge contributor to this picture, he has an extraordinary sense of gesture, of finding visual metaphors.” They worked together to develop the script both before and during the production.

“When we came to rehearse this interrogation, Lee was supposed to ask a number of questions. ‘Where’s Reese?’ ‘Who brings the money every month?’ etc. After shooting out the bed, with its obvious sexual connotations, we played the following scene with Walker spent, post-coital. He tips out the empty cartridges, and the gun flops down. The penis parallel is rather overt, but mitigated by graceful slow motion.

As we rehearsed, the actress, Sharon Acker, getting no questions from Lee, waited, then simply went through her lines. Lee was signaling to me that it was impossible for Walker to start questioning her in his depleted state. We were about to shoot. The set was lit. I quickly rewrote her responses so as to include the questions: ‘Reese? I haven’t seen him. The money? A guy brings it. First of every month.’ Lee sat impassively as she answered his unasked questions.”

Excerpt From

Adventures of a Suburban Boy

John Boorman

In addition to finding metaphors and helping with the script, Lee would bring personal emotions to his character to help drive the narrative.

When Walker finds that his wife has committed suicide, Marvin portrays genuine pain on screen. In the same year as filming “Point Blank,” Marvin’s long-term partner, Michele Triola, also attempted suicide with an overdose of pills, mirroring partly the fate of Walker’s wife. The filmmakers designed the shot of Lynne’s perfumes spilled in the bathtub to represent her essence draining away visually.

A few years before his death, Marvin ruminated on these parallels between art and reality: “I saw Point Blank at a film festival a year or so ago and I was absolutely shocked. I’d forgotten. It was a rough film. The prototype. You’ve seen it a thousand times since in other forms. That was a troubled time for me, too, in my own personal relationship, so I used an awful lot of that while making the picture, even the suicide of my wife.”

Gay:

Point Blank pushed the boundaries of contemporary Hollywood film production and subtle progressive ideas. If you’ve seen the film, you might find it surprising to find out the filmmakers meant to infer homosexual overtones between Walker and Reese. In this scene, they wade through a sea of men to find each other at the all-male party, symbolizing the path of past lovers. When Reese takes Walker to the floor, he man handles an uncertain Walker, and Marvin reacts like a passive girl. This idea is echoed further when Walker dumps Reese out of bed, becomes the alpha, and climbs on top of him. Or how he continues to yank on the phallic sheet.

Boorman said: “I think I inadequately explained his relationship with his friend; I wanted to build up this sense of comradeship with his friend, with homosexual overtones.”

A few of you may be thinking there would be no way an actor like Lee Marvin would play a gay man in 1966. But an interview with Marvin by Playboy in 1968 would say otherwise. Could you ever impersonate a homosexual on screen?

MARVIN: It would be easy for me to play a homosexual. Now that I know where I stand, I can indulge myself in such things without any fear.

In the nightclub fight scene, Marvin again performed most of his own stunts, battling two stuntmen acting as henchmen. He accidentally knocked loose a stuntman’s tooth with a mistimed blow. Marvin also potentially delivered the first groin punch in a major motion picture. Patricia Casey, a 26-year-old former ballerina, choreographed the fight scene. She also hired the club band, The Stu Gardner Trio, whose song “Mighty Good Times” they recorded live over four nights. As previously mentioned, Casey, the assistant and later wife of producer Judd Bernard, played a crucial role in the film’s existence. She was the one who initially read the script and suggested to Bernard to purchase the rights.

Point Blank became the first major motion picture to equip every cast member with concealed wireless microphones, setting a precedent for almost all TV and movie productions today. In 1966, the norm was to use a boom mic, which often captured unwanted ambient noises, necessitating post-filming dialogue re-recording. Director Boorman combined boom and wireless mic audio in post-production for optimal sound quality. Although Point of Evil, Mutiny on the Bounty, and My Fair Lady had previously used wireless microphones on a limited basis, Point Blank pioneered them extensively throughout filming, with 125 custom mics produced for the project.

The Los Angeles home where Brewster met Walker one year prior was the actual crash pad for The Beatles after their 1966 US Tour. The Fab Four played pool in the same room where Chris whacked Walker with a cue stick, and they enjoyed the swimming pool with fellow musicians David Crosby and Joan Baez. Ironically, Paul McCartney and John Lenon derived their group’s name from the name of Lee Marvin’s character motorcycle gang, the Beetles, from the movie The Wild One.

In 1998, Hollywood cameras rolled into the Los Angeles home to film the TV movie “The Rat Pack,” bringing Ray Liotta and Don Cheadle to life as the iconic Rat Pack members. The following year, Rock band Lit used the home as the backdrop for their music video Zip-Lock.

Drew Barrymore acquired the 8,000-square-foot property in 2002 for approximately $3 million. She allowed the British rock band Radiohead to use the house for a three-week recording stint in 2010 for their album “The King of Limbs.” Barrymore eventually sold the property in 2018 for $16 million.

According to the director, John Boorman, Lee Marvin was so drunk for this scene “The grips knelt one each side of him and supported him at the hips. We adjusted the shot so that they were just out of picture, then I stood by the camera so that I was in his correct eye line. ‘Lee, look at me. Lee! Can you see me? See me!”

Was Walker dreaming?

Some people believe the movie is a dying man in the thralls of death and is a fever dream of sorts, and the entire film is a figment of Walker’s imagination. Or Walker is a wandering ghost who must satisfy his cravings for vengeance on his wife, friend, and all involved before he can rest.

Why do they think that?

Walker doesn’t directly kill anyone. Instead, his presence induces them to kill themselves and each other. The closest he comes is in the scene where John Vernon falls off a balcony during their struggle, and even then, it’s somewhat ambiguous how deliberate that was on Walker’s part.

Walker is shot at point-blank range, and both bullets tear into Walker’s stomach; they are the sort of wounds that prove fatal in nine out of ten cases. But Walker survives the blasts? And miraculously gets across the channel, with freezing water and deadly currents, between The Rock and the mainland? Either this is far-fetched, or a man dreaming.

Walker’s hair goes from dark before being shot to ghost white when he reemerges on the tour boat.

Lines in the film that directly reference Walker being alive or not.

Lynn asks Walker if it is good to be dead; the waitress in Chris’s club says, “Walker, are you still alive?” and Chris tells him that he “really did die on Alcatraz” and that he “should just lie down and die.” Additionally, the image of Reece shooting Walker recurs constantly, as if to remind the audience that Walker could not be alive. Lynn asks Walker if it isn’t “good …. to be dead.” Later, her sister (Angie Dickenson), halfway through the film, tells Walker

“You died at Alcatraz all right.”

After Lynn’s suicide, we have no clear notion of the passing of time. As Walker moves from one room to another, he remains the same, but the rooms are substantially changed, and Walker seems almost surprised, as these scenes are continuous to him. Walker crouches in the corner, marred by shadow – an image suggesting he’s never left his prison cell/coffin on Alcatraz.

At the end of the film, Walker finally has the opportunity to get his money, yet he doesn’t. Walker remains in the shadows as the mob boss leaves without the money. Walker fades into the shadows and leaves the money where it is. The ghost has his vengeance. A ghost does not need any money. The purpose of his return from the grave is accomplished, and now he returns to the shadows and death.

Some movie reviews and podcasts about Point Blank say Boorman never states if the film takes place entirely in Walker’s head; this isn’t 100% accurate. Yes, in some interviews, Boorman says the viewers should decide for themselves, but he has also alluded that Walker does die in the beginning. In his Michel Ciment interview, he states, “Seeing the film, one should be able to imagine that this whole story of vengeance is taking place at the moment of his death.”

In a 2015 Sight and Sound interview, he stated: “I struggled to get an ending there. And finally, I decided, he just gradually fades into darkness – a series of shots in which he just sort of disappears. A lot of people found that unsatisfactory: he doesn’t take the money. [But] that was okay, because it wasn’t about the money, really. The fading away was to suggest that possibly he hadn’t really existed at all.”

Ending:

The ending of the movie completes the circle. (It starts and ends with Alcatraz Island.) Some fans of the movie are not fans of the ending. Including the co-writer Alex Jacobs, who had his own ending he liked better.

“We had a grandstand ending which I liked very much, because it seemed to me to be sort of Wagnerian in its own way. In this fort, Fort Point in San Francisco, you had Yost revealing himself to Walker and tempting Walker to join him, and Walker is half-tempted and half-shat-tered by his experiences and by the fact that he’s been used as a dupe for the whole film; all his passion, all his energy, all his madness were being used–he was like a puppet being manipulated-and he becomes absolutely incensed, and he advances upon Yost who has a gun, and Yost is suddenly terrified by this mad force, because Walker is now completely insane. And Walker just advances upon him–he’s going to kill him with his bare hands, a complete animal, he’s frothing at the mouth. And Yost shoots him three times and the three bullets miss. Yost actually cannot shoot this force. He tries, his hands shake, and he suddenly realizes his age; suddenly his age sinks through him like a flood, like a great stone sucking him under, and he’s a completely old man, and he steps backward and falls off the parapet and dies. And Walker comes to at the edge of the parapet, and shaken and quivering is led away by the girl out into the world again. This was the ending we had.”

Angie Dickinson told an interviewer another ending: “Well, in the original script there was a different ending. Walker comes back and picks me up and we drive off together, which was a kind of cliché happy ending. But John Boorman stuck to his guns and he changed that ending, because he wanted to keep the film in tune with what the story was really about, which was Walker’s revenge and his getting his money back.”

In “The Hunter,” the basis for “Point Blank,” Donald E. Westlake initially planned to kill off the Parker/Walker character at the end of the book. However, his editor persuaded him not to, enabling Westlake to write 23 more books featuring the character.

Editing:

During the editing phase of the movie, director Boorman was confident in the expertise of his editor, Henry Berman, an Oscar winner for his work on “Grand Prix” (1966), and Boorman himself had a background in film editing. However, their process was constantly interrupted by producer Judd Bernard, who insisted on overseeing their work and frequently criticized the film’s bleak tone. He even threatened to take control of the editing post-filming. To counter this, Boorman filmed minimally, limiting the possibility of significant post-production changes. Despite this, Bernard remained a persistent annoyance in the editing room.

The situation changed after Boorman presented the film to Margaret Booth, MGM’s respected supervising editor, known for her stringent re-editing of films she deemed subpar. Boorman and Booth connected over their admiration for D.W. Griffith’s works; Boorman had recently directed a documentary on Griffith, “The Great Director” (1966), and Booth began her career editing for Griffith in 1915.

Booth suggested only minor edits after watching the film. Post-adjustments, she presented it to MGM executives, who, confused, contemplated further changes and reshoots. Booth, however, firmly opposed any alterations, stating that any change would be over her dead body.

Boorman stated in 1968 that he felt the MGM executives did like the movie: When they saw the film, how did they feel about it?

They were very pleased. About halfway through my shooting period, Blow-Up came out and had a big success, which was a great help to me, because when I put the picture together, it wasn’t entirely explicit, and since Blow-Up was their picture, they figured this must be the contemporary style, so they didn’t worry about it too much. No, they were delighted with the film. There was a lot of hostility from theater owners, who couldn’t follow it; they’re the most traditional of all, aren’t they? But it got an audience. And it’s been very successful in Europe, in France and Germany particularly. I just got some reviews from France, which were tremendous, but that’s probably because they couldn’t clearly follow the flaws in the script.

Music:

Not only was Boorman’s film editor an Oscar winner but so was his music composer, Johnny Mandel. The same year Marvin won his Oscar, Mandel won his gold statue for Best Music, Original Song from the movie “Sandpaper” (1965). The song that most people know of Mandel’s prolific work would be the intro to the 1970s movie and long-running TV show M*A*S*H.

Unlike many composers, Mandel was on set during the filming of Point Blank. While on Alcatraz Island, he found an out-of-tune piano in the jail basement that had been there for decades. This helped inspire him to create a surreal, disconnected score and combined a group of unique instruments and effects to complement director Boorman’s stream-of-consciousness approach to the movie. It’s more tonal than melodic. Mandel based his 45 minutes of music on a minor 12-tone score that utilizes tapes running at half speed. Later Mandel said: “A lot of fun to do that movie, work, but fun, that’s one of the more rewarding ones.”

Reception:

Five days before the film’s gala world premiere, Life Magazine devoted three full-color pages to leather fashions photographed on Alcatraz Island and modeled by the film’s leading ladies, Angie Dickinson and Sharon Acker. Several of the outfits illustrated comprise part of the national “Point Blank” fashion promotion with Highlander Clothes. Over 60 major stores throughout the country participated in this promotion.

“Point Blank” premiered in San Francisco on August 30th, 1967, and rolled out worldwide over the next six months. The exact box office gross of “Point Blank” in 1967 remains unclear. Most online reports suggest a figure of $9 million, citing an interview with the film’s two producers in 1968. However, this number likely skews high, as it includes a speculative phrase, “may very well gross $9 million.” Noted film author Howard Hughes reports that the US release earned only $3.5 million. A more accurate estimate might be around $7 million, equivalent to $64 million in 2024 dollars, ranking it 32nd among the top 100 movies for 1967. While respectable, it wasn’t a blockbuster, especially compared to Lee Marvin’s other 1967 release, “The Dirty Dozen,” which grossed $51 million, or almost $400 million in 2023 dollars.

Two weeks before the premiere, MGM did some test screenings. Of the 166 people who participated, 74 felt it was excellent, 44 thought it was good, and 48 thought Point Blank was fair or poor. Ninety-three would recommend it to their friends, while 37 wouldn’t. People loved Marvin overwhelmingly but were not fans of actress Sharon Acker.

Some of the comments left were:

“Film editors must have been drunk because Lee Marvin is a great actor and this movie is quite beneath him.”

“Too many flashbacks,” “Tired of violence and sex just for the sake of violence and sex.”

In the United States, the film struggled to gain positive reviews. Critics were either put off by the level of violence, the script, or they failed to appreciate the distinct foreign film style that Boorman incorporated.

Some forward-thinking critics like Roger Ebert from the Chicago Sun-Times got it, saying: “As suspense thrillers go, Point Blank is pretty good.” Giving it four out of five stars.

Or Bosley Crowther of the New York Times

This much must be said for “Point Blank,” the crime melodrama came in a blaze of gunfire and color” “it is a spectacularly stylized and vividly photographed film that hints at some of the complex organization and hideous inhumanity of the modern-day underworld.

However, many of the reviews were not favorable.

“The director proves that he is “switched on, but raises doubts that he is “tuned in.” The resulting voguishness will date the film quickly.” “Boorman and the screenwriters play with time throughout the film, the easiest explanation being that it is a necessary diversion to disguise the weaknesses of the script.” John Mahoney The Hollywood Reporter

“Point Blank is one of those forgettable movies in which only the settings change the violence remains the same.” Time Magazine

“Violence Blank and Pointless.” Richard Schickel Life Magazine

“director John Boorman gets so carried away with tricky camera shots and flashbacks that his film becomes consciously arty as well as confusing.”

“Director Boorman and his scriptwriters forget to tell us how and where certain key things happen”

“As far as I’m concerned, “Point Blank” draws a blank.” Commonweal 10/6163

Let me note first that nothing I have to say about what happens in this movie is guaranteed to be accurate; [the writers] have decked their simple and savage tale with such showoffy gewgaws of flashes back, forward, and sidewise, and have left so many critical facts either untold or unexplained, that any six members of a given audience would be apt to recount six different versions of the plot. Brendan Gill The New Yorker

Boorman admitted in 1968 that some of the criticism was valid by saying: “the critics did attack the film, rightly, for weaknesses in the script.” “I know that I certainly couldn’t write American dialogue, although I did quite a lot of it in Point Blank. Perhaps that’s one of the things that’s

wrong with it.”

But as time marched on and once the home movie revolution started via video rental stores, Point Blank became a cult classic. And now the general thought amongst critics and fans is overwhelmingly favorable.

Metacritic 86 metascore

Rotten Tomatoes 92%

IMDB 7.3 with 23k ratings

Letterbox 3.9 out of 5

Martin Scorsese showed his love for the film by putting the movie poster in this scene from his movie Mean Streets (1973). And then, in 2010, saying, “This was one of the first movies that really took the storytelling innovations of the French New Wave—the shock cuts, the flash-forwards, the abstraction—and applied them to the crime genre. Lee Marvin is Walker, the man who may or may not be dreaming, but who is looking for vengeance on his old partner and his former wife. Like Burt Lancaster in the 1948 I Walk Alone, another favorite, he can’t get his money when he comes out of jail and enters a brave new corporate world. John Boorman’s picture re-set the gangster picture on a then-modern wavelength. It gave us a sense of how the genre could pulse with the energy of a new era.”

After Paul Thomas Anderson first saw John Boorman’s Point Blank, he was so obsessed with it that he scoured the city to check out all the locations Boorman used.

“a film that I’ve stolen from so many times.” Co-host of Point Blank’s DVD Extra and director Steven Soderbergh is an obvious fan of the movie.

Point Blank’s influence on future moviemakers is undeniable. But there are some repeated movies said to be influenced by Point Blank that weren’t. Countless times on the web and in books, Christopher Nolan’s Memento is mentioned to have been influenced by Point Blank. But Nolan has stated he never saw Point Blank before or during the making of Memento. “it’s a rather surprising fact. I can certainly understand the parallels,’ admits Nolan. ‘It’s very similar in the way it starts, throwing you into this chronological turmoil. Also, the revenge motif, it’s taken to such an extreme. I’m never surprised to see other films people have made that have done the same kind of things as me; we’re all working in the same realm, and we’re all drawing from everyday life, and books and experiences.” -The Making of Memento.

Claims of Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs being influenced by Point Blank are unsubstantiated. Beyond mentioning Lee Marvin, the film lacks any tangible connections. Tarantino himself has said that he is not a fan of Point Blank, except for its first 10 minutes. He considers The Outfit (1973) the best Parker-related movie and prefers Marvin’s performance in The Killers over Point Blank.

What’s next:

Not long after the premiere of Point Blank, Marvin brought another project to Boorman about an American airman and a Japanese naval officer who is washed up on a tiny island during the Pacific War. Boorman was not thrilled about the story, but how could he refuse the man who lifted him up from obscurity? They made Hell in the Pacific (1968), but that would be the last movie they worked on together. Boorman would continue to offer roles to Marvin, but for various reasons, it never worked out. They remained great friends until Marvin died in 1987; Boorman even named his son after Marvin.

After completing “Point Blank,” producers Bob Chartoff and Irwin Winkler adapted another novel by Westlake, “The Seventh,” into a film titled “The Split” starring Jim Brown in the role of Parker. The duo would go on to produce many hit and critically praised films like Rocky (1976), Raging Bull (1980), and The Right Stuff (1983)

Post Point Blank Producer Judd Bernard went his own way from Chartoff and Winkler’s and never replicated their level of box office and critical acclaim in subsequent projects.

“Point Blank” redefined the crime thriller genre, wielding new stylistic and narrative techniques. It forged its path, redefining character archetypes and blending movie genres in a way that challenged the very fabric of Hollywood filmmaking. Its influence continues to echo through the corridors of film history, inspiring filmmakers and captivating audiences with its timeless allure and profound impact on visual storytelling. “Point Blank” stands as a powerful testament to cinema’s ability to transcend the boundaries of time.

Ending:

Boorman said: “I make no distinctions between reality and fantasy. Confusion of the mind, depicted on screen, is very difficult to communicate without confusing the audience. If people’s emotions are assaulted by the picture, we’ve done our job well.”