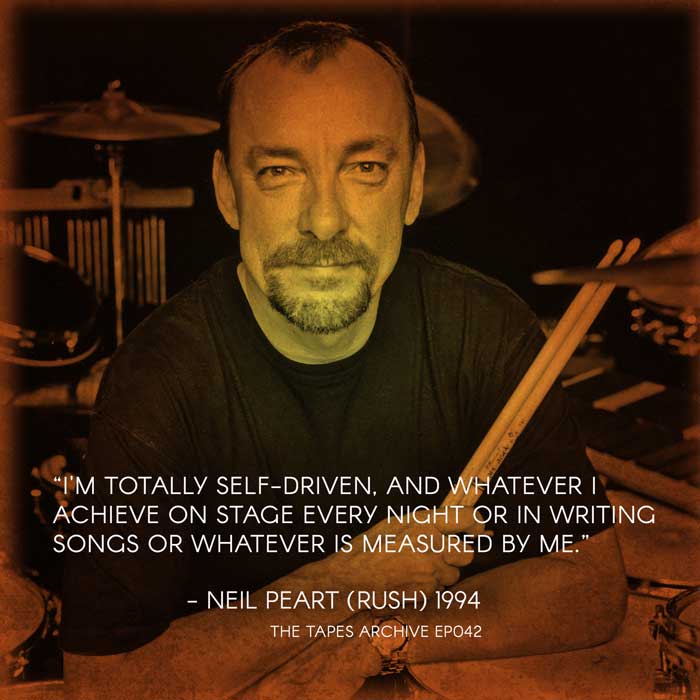

Neil Peart (Rush) 1994

A never-published interview with Neil Peart

In the interview, Peart talks about:

- Thoughts on Rush’s album progression

- What kind of difference can one person make

- The western idea of heroism

- The luxury he enjoys

- How people react to him asking them to think

- What he learned from Paul Simon

- Why he agrees with Frank Zappa that love songs are destructive

- How he’s a dreamer and an idealist

- What characteristic he has that has enabled him to be successful

- His thoughts on Rush Limbaugh

- His play on words that no one gets

- Who he thinks Rush’s audience is

- If he thinks his audience is smart

- Existential questions he asks himself

- How long it took for him to master the dums

- His pick for young and upcoming bands

In this episode, we have our third and final interview with Rush’s drummer, Neil Peart. At the time of this interview in 1994, Peart was 42 years old and was promoting Rush’s album Counterparts and their concert in Indianapolis. In the interview, Peart talks about how Rush progressed over its first 18 albums, why he agrees with Frank Zappa that love songs are destructive, and what characteristic he has that has enabled him to be successful.

Neil Peart Links:

Watch on Youtube

Neil Peart interview transcription:

Neil Peart: Our division of labor system, you know the other guys deal with radio and TV and meet and greets, and I talk to the real people.

Marc Allan: Well, believe me, the real people are happy for that. Well, let me start by asking you a question you ask on the album, what kind of difference can one person make?

Neil Peart: I mean, obviously I believe that one person can make a difference in role models. Actually, that line reflects really nicely along that it’s not even in nobody’s hero idea. You know, the people I held up in that time that were examples and role models to me, for instance, the first gay person I ever knew who’s had such a great example of what gay people can be and prevented me from ever becoming homophobic or from having some kind of weird idea about what homosexuals were about or in the second verse of nobody’s hero to one person taken away from a family and the gap that, that leaves and the people around them and how it affects their outlook on humanity. You know, my question about those people was how can they ever think human nature is good again they’ve lost their daughter in an act of mindless brutality. So both kinds of questions do have to do with, of course what difference one person can make, and the question of heroism to our Western idea of heroism is something I’ve thought about a lot over the last few years, thinking about what is it, first of all, and the, the question be, is it good? And I decided, no, it’s not good. It’s not a role model at all, people are holding up these deities of perfection that they can’t possibly measure themselves against or aspire to. So a true role model to me, can be someone in the nobody’s hero sands, a few school teachers that I had, a few musicians that I worked with in early years, that set examples for me that I continue to live by, even though they weren’t Michael Jordan or Michael Jackson. So those were the examples I was trying to hold up that what America and the Western world needs is not these kinds of semi defied heroes at all. We just need good examples in our neighborhoods when we grow up really makes much more difference.

Marc Allan: That’s a good point, I guess it really comes to light now, if you think about this Nancy Kerrigan stuff people are being held to impossible standard.

Neil Peart: Yeah. And that’s what it is, but contradictory ones, I mean in certain walks of life, you can get away with some things, and yet people like politicians, they’re supposed to be pure than Caesar’s wife and yet, you know, rock musicians it’s okay for them to be jokey that drunks and women beaters and everything but they mustn’t sell out to the corporation. These kinds of things that are so contradictory and so strange and the morality of athletes to again, what they can get away with and what they can get away with are really strange constructs to me. And in different walks of life, you know the different standards that that people are held to. And that is how it is, you know, the, like you say Nancy Kerrigan, that whole thing is another amazing example. And the amount of print that it’s taken up with personally, I’d much rather read about Audra James and the mall in the CIA and the continuing existence of the KGB and what that means in the world. I’ve been really feeling robbed last few days in the newspaper because what’s really important. What’s what’s really going on is get bumped away by the lowering of budgets and all that bullshit, You know, that’s annoying, but these people they made a difference. One person makes a difference.

Marc Allan: Yeah. It seems to me that while most adults kind of retreat and stop questioning things in their life, you seem to go in the opposite direction. I mean, your each album continues to question and expand your thoughts more and more.

Neil Peart: Yeah, I think it’s a luxury of the job. Honestly, I was talking with a friend of mine the other day, who’s a writer and I was saying, we’re lucky to be in this position where I think, it was John Steinbeck said, ‘What’s the hardest thing for a writer’s wife to learn is that when he’s looking out the window he’s working.” So those kinds of things that you are actually paid to sit around and think about stuff. And I find that really refreshing not only does it reinforce my sense of the value of the job but also my right to sit around and re-examine things. I’m off my own preconceptions too sometimes. But each one is a progression of learning and things that I’m talking about and counterparts, I certainly didn’t know about 10 years ago, or I think about 10 years ago. These dualities of race and gender and so on have been hard one insights for me years of traveling around Africa, for instance has helped me to understand that. And years of trying to understand men and women and how they behave have led me to certain insights and other people’s work, of course that I’ve studied and learned from contributes to that. So yeah, the questions number closed for me. And that’s when I am surprised by the kind of people you mentioned, people I grew up with certainly who at a certain point just stop asking and whether they accept a system of religion or a system of political thought or even just no system, you know, they just decide that their lives are too full for that. And that’s fair enough too, and that’s when I say, that those of us like yourself too really who are in a position where you are, you know your job is to investigate things and reach conclusions that maybe other people haven’t got the time for. I think people like you are humorous, too, as indicators, I really value the world of humor that points out things that are worth laughing about in the late eighties like a hotspot magazine was such a valuable service because it was an indicator of things that were worth laughing about or perhaps being a little cynical about it

Marc Allan: The thing that I guess you get to do, that other people don’t, as you can sort of go right to the source, or at least it spend more time thinking about it. Whereas other people are looking toward maybe not role models, but other people to tell them what to think because they seem to be too busy to worry about things like that.

Neil Peart: Yeah. And like a tide sometimes that is fair enough, and I do appreciate that luxury and also take the responsibility of it seriously, you know that anything that I do dare to come out and say or a state is pretty carefully researched. And, you know, it was my very best effort at putting some kind of hard won knowledge into imagery and a rock’n’roll format if you like. So yeah, I don’t deny the luxury of it but at the same time, it is a professional obligation in another sense that you are supposed to think hard about these things before you just toss up some piece of rock lyrics, but at the same time, I do appreciate that the idea that they are timely and again to make the analogy with journalism that you’re reflecting the times in which you live and someday somebody might go back to your newspaper and look up a column for historical reasons but it’s relevance really thesis on the day, and rock music to me is made to have the same kind of timeliness and built in obsolescence where eventually it becomes irrelevant. And that’s why the constant metallic nostalgia for sixties music or fifties music or seventies disco or whatever is a blind alley. You know, it’s trying to recapture another time and it’s nostalgic just as silly as trying to bring back Dixieland or the roaring twenties or the gay nineties, it’s gone.

Marc Allan: People don’t want to let it go. And for-

Neil Peart: No, oftentimes a represents the best period of their own lives. Or there’s also the concept I’ve been reading a bit about lately of nostalgia for times when you didn’t even live them. And I felt that too, you know, if I am in Paris I feel the Paris of the twenties is a strong sense of nostalgia. I wish it were there, you know and I regret the fact that it’s all gone, and if I’m in London, I can’t help but think of Dickensian time and traveling around the United States I can’t help thinking of, you know, the other progress of the century in the small towns and cities of America the fifties in New York city, for instance and another time that I didn’t live in but I feel a kind of analogy for, it’s a complicated thing.

Marc Allan: You’re always asking people to think and how do people react to you?

Neil Peart: That’s an acquired skill too. I think I’ve learned better over the years to invite people too, and, you know it’s something I think Geddy pointed out to me when I was trying to do Manhattan project, and here I am trying to write the history of the Nuclear Age, basically capture the context of the times in which the atomic bomb was born and how it changed the world. But the true, good intentions of the people who did it, you know, that it wasn’t the cartoon idea of these evil scientists trying to create the ultimate bad weapon. They were simply trying to save their country and do the right thing. But in the process of that, of course it’s very hard to tell again, putting it to the context of a rock song to try to write a historical treaty. And it was Geddy that gave me the idea and that song in every verse to make it an invitation imagine a time, you know imagine a man inviting the listener into this, you know scenario that I was trying to present. So I’ve always kept that idea in mind that if I am presenting, you know, a conceptual idea or some abstraction, but I’ll try to make it an invitation and to make it warm too. I had a real problem in Roll the Bones, our previous record cause I was dealing with the idea of chance and I was saying, and putting forth the idea that chance has an enormous impact on our lives just in the sense of contingency, but it’s a repellent idea. It’s cold, so I had to work really hard to warm it up with imagery and specific human examples and so on. And to make it not seem hopeless to make it, yes there are these odds, but we couldn’t manipulate the odds and we can roll the dice over again. And with this album to dealing with abstractions like you are with them, I didn’t want it to just a concept. So I had to find a way to warm it up. And I used them little biographical vignettes of people on the other side of the abstraction to make that example or in the song everyday glory. You know, I talked about it an abusive household and a distant dysfunctional family but he tried to emphasize the fact that you could transcend that. And people I know that have grown up with retro childhoods have transcended it sometimes. And like the whole gist of that song everyday glory, that, you know, if things are dark well we’re the ones that have to shine if it can still be done. So the element of hope is so important to get in there and the warmth of the human element in there certain songs where I’m talking about relationships but they’re not by any stretch autobiographical. I just again, had a concept to deal with and what love was and how people stayed together. So I invented characters to dramatize my scene, you know the cold fires, an example of that. And at the speed of love previous records, I’ve done that on songs like goes to the chance. On the song, Presto itself with an imaginary couple, having a disagreement. And I was playing, I learned, I guess from Paul Simon the idea of putting a conversation in the song, he said, she said idea. I thought it was a very cool way for me to present opposing viewpoints and in cold fire I wanted to set it up, but you know, again, this is a real life love story, and there are two of the two characters, the woman is the smart one. So it was a delicate bit of Tradecraft. just the craft that it took to create these characters and then set up the balance of their relationships so that it’s not obvious. I don’t think to the listener that the woman is the smart one and the guy’s asking dumb questions. But the conclusions become obvious that I’ll be around, if you don’t push me down too far to me, you know this is a realistic evaluation of what keeps people together, as long as you live up to each other’s expectations and you are still the same person, but you know they plated their trust too or whatever you will maintain their love. And I thought that was more realistic than the idea that love is made in the stars and will last forever at some moment of bliss. Frank Zappa did an interview shortly before his death and he was someone asked him, you know you’d never write love songs, Frank. And he said, well, no, not on here. Love songs stupid, but they’re destructive, and they have probably destroyed more relationships over the past few generations than anything else because it creates this unreal expectation of what a relationship is supposed to be and what Prince charming and Cinderella are supposed to be like while they live happily ever after, you know that whole myth. And I agree with him, again, it’s not only dumb all those love songs, but they are actively destructive and do cause people to have unreal fantasies of what their lives will be like and to be disappointed obviously, and disillusioned by them. So

Marc Allan: Well, this goes back to what you’re saying regarding heroes and nobody’s hero. It’s unrealistic expectations.

Neil Peart: I think expectations. I mean, I’m a dreamer and an idealist to the max and obviously I dreamed up what I am. You know, my life is certainly a dream realized and I’m not denying that by any means, but I’m saying that it was achieved by small increments. I didn’t pick up a pair of drumsticks and say I’m going to play Madison square garden. You know, my dream was playing at the local church halls. And then once I played there my dream was playing at the high school. And then once I played there, you know, the local dance hall and so on, you know, realistic goal of again, one by one and same as a musician, you know, to attain levels of skill, again, I didn’t say on the first day I’m going to be better than Buddy Rich. I thought I’m going to be better than Tommy Jones down the street. That was my, that was the limit of my goal. And it was, that’s how it should be in each of those goals led to another one. And again, in any reputation, I just I can fight my own life as an example that yes I had this dream and yes, I actualize this dream but I didn’t do it by pretending to be a semi deity or comparing myself with one either, it was just a series of reachable goals, one at a time.

Marc Allan: Beyond ability do you think that there’s something some sort of characteristic that you have that other successful famous people have that enables them to get where they are?

Neil Peart: Oh, ambition is the puzzle drove it that without ambition really nothing happens. So In every case, there’s some kind of ambition now what is driven by various and it’s driven by insecurity or a need for approval with a lot of people certainly in the entertainment world with some nice quotes around that it is a need for approval. And for a lot of people I find the celebrity for them is nourishment. You know, they need to be loved which is exactly the opposite of mine. You know, my I’m totally self-driven and whatever I achieve on stage every night or in writing songs or whatever is measured by me. And, you know, I know when I walk on stage how well I’ve done compared to how well I should have done it, et cetera. And it’s a pretty much internalized ambition. So it varies a little bit but certainly the magic word and the missing word in cut to the chase to it is the fire that lights itself the missing word there is ambition is the fire that lights itself. And although I adapted it from a quote I read it to somewhere I quote that said “Genius is the fire that lights itself.” And I think it was a Nobel physicist that coined that phrase. And I thought, Oh, that’s a beautiful little phrase, and then I thought, wow, you know, genius is okay, but for me, the word I was on at the time thematically was ambition. I thought, well, ambition is the same way whatever your goals are, or even in the smallest way in your hobby, whatever you want to attain it lights itself. You don’t have to say, Oh, today I must go and paste stamps in my album, or I must do a hundred mile bike ride or the private ambitions that people have in their lives and have to be self-driven there’s just no way you can force yourself to be ambitious. So the concept of ambition in that song “Cut To The Chase” was the underwritten theme of the whole thing and certainly the motor of the Western world. And certainly not without its dark side to it, as you know cut to the chase is about ambition in the same way that “Big Money” was about economics. And in both cases, I wanted to point out that it does some good stuff and it does some bad stuff. There are no clear, good and evil characteristics here that sometimes money is a force of good, and sometimes it’s a force of evil and the same with ambition.

Marc Allan: So there’s a lot of shades of gray around-

Neil Peart: Well, yeah, sometimes I mean, the absolutes are difficult or I do believe in good and bad but it’s more complicated than a day’s reflection will satisfy a lot of these songs are investigations I guess sometimes they’ll be gray areas but without denying the black and white reality too.

Marc Allan: People want a very simple division, they want liberals or conservatives, you know they want that.

Neil Peart: That’s the other thing too.

Marc Allan: I don’t think there is such a thing, I don’t think everybody’s a hundred percent anything.

Neil Peart: Not very often, no. And unfortunately though one side gets tired with the bad brush, like in the in the whole right wing world of American politics. I see the good right in the bad, right. And when I see somebody like Rush Limbaugh I’m appalled not only by him, but by the people around him but this kind of mentality can exist to poke fun at such righteous events. And people had to do one episode of the show I’ve ever seen. They just poked fun at this black woman was making a beautiful speech about how, okay, it’s time for us to be more selective in whom we choose, you know, black people up from that have been proud to vote for other black people regardless of their record, you know regardless of their fitness for office. So on someone a few weeks ago and they had been hosting a radio call-in show where people were calling in and making comments about our new album, I think, and one of them called in and said that “Nobody’s Hero” was really about, get it, it was really about, what I was really saying was that it was time for us to stop making heroes of the victims like AIDS victims, and homosexual victims of domestic abuse. And I was saying, that these people really aren’t anybody’s hero and we should stop making anything out of them. And that was the point of the song and the commentator at the time said, I think you’ve gotten them confused with the other Rush and otherwise because sometimes, these interpretations just I can’t believe what people get out of it. And other friends of mine have told me that it’s a friend of mine and people, other people knew that, you know, he was finally with me. So he said, this is a true, that rush are gay, just because I dared to write about a homosexuality, couldn’t be clearer that, you know, I went to his parties that’s the straight minority. It can’t be more clearly stated than the way I did it, but

Marc Allan: Yeah, it’s ironic. Cause the next question I was going to say next thing I’m gonna say was there’s such an error tolerance in your lyrics, you know to be tolerant of other people.

Neil Peart: Yeah. well, I was careful in the song “Alien Shore” too. You know, I said to us, you know we’re strangers by a chromosome, but we’re we still want to reach out to each other as males and females and culturally, I made the point in the song too, that racially, yes, we are different. But my wonderful little play on words that nobody gets is that race is not a competition pine on race. You know, I just wanted to make it clear that for me kind of the clear germ of the counterpart’s idea was the dictionary definition but it’s a duplicate and yet an opposite. And that’s how we are in these dualities, you know, we’re the same but different. And I thought, okay, that’s beautiful. And self-evident, and among my friends that’s an accepted reality, but the chorus line of the song comes back around, but that’s just us. I had to realize that you given me, we might agree, but that’s just us, you know, we’re right. Thinking people and most people aren’t or a lot of people are and they’re behaving badly and saying terrible things, and they’re obviously not perceiving the same reality we were. So yes, I don’t want it to put to a sort of professors’ tolerance and express it in words. But at the same time, admit the fact that I wasn’t being naive and I wasn’t trying to put forward a sixties kind of thing of all we’re all the same and we should just get along. The key of part of the song had to come back to, okay well we think these things, but sadly that’s just us reaching for the alien shore. Most other people are trying to blow it up.

Marc Allan: Can you give me a broad brush stroke of what you who you think is in Rush’s audience.

Neil Peart: That’s pretty difficult, really just over the passage of years. And there’s been a constant recycling of our audiences. Some people, as you said, really are, they lose interest in music and you know, the guy attached to job and mortgage and family and so on and, you know, fair enough whatever makes you happy, it’s not a problem, but they stop of course coming to rock concerts and younger people step over or step into it. So certainly there are a lot of teens in our audience who literally were not born when we first started touring the United States. So that’s kind of interesting, but at the same time we see a lot of people in their thirties and forties and sometimes they’re with their families, and there was a guy in the second row the other night in one of these shows in Florida wearing a power window t-shirt. So he’s obviously a long time campaigner and a very dignified, well taken care of looking guy and not making a fool of himself, obviously there, because he wanted it to be a totally enjoying the whole thing. So it was kind of inspiring to us. He was an adult. And one thing we’ve always tried to do certainly is to speak to our peers who talk about our development of ideas as they’ve changed, and our music has it’s changed as far as we’re concerned we’re addressing equals and not trying to talk down to our audience or be pretentious over their heads or anything like that. We’re just talking to other people like us, again like the point of alien shore, you know you and me, we might agree, but that’s just us, and as far as we’re concerned the people were writing to her or people like us, so we are happy to see people that have grown up with us. And more and more, I got mail from people who are out in the world themselves now doing interesting and worthwhile things, but Rush still part of their lives you know, in a sense like I’ve always loved that. Quote, one of my friends said that we’ve been the soundtrack of his life. And to me that’s like the ultimate compliment, right. Can stay relevant to somebody life through their teens their twenties and into their adulthood is it’s great. I mean, obviously the reflection of our lives through that same time period but to be able to maintain contact with someone else’s life through that I think is, well if it’s not a miracle, it’s at least a very wonderful thing.

Marc Allan: So you think your audience is smart?

Neil Peart: Yeah. I think they’re as smart as we are. Absolutely. I never, I never worry about being too complicated or too deep or anything like that. I just take for granted that if we can think of this and if it gets us excited, then you know other people can understand it and that might get them excited too.

Marc Allan: Okay. Cause I was, when I was asking about who the audience is, I wasn’t really thinking age so much as I was thinking of mental makeup.

Neil Peart: Yeah they are tough to generalize though, because there were a lot of people there who don’t pay any attention to the lyrics for instance, and that doesn’t bother me because I, you know I only spend two months, every two years as a lyricist. So it is a small part of my time. And I do a good job of it just because I’m doing it. But at the same time, I don’t overrate, it’s important. And I know that it’s very possible to like music without paying attention to the words. So that’s fair enough. So there are a lot of people that are just there to shake their heads around and rattle their brains. And that’s fine too. And they’re the air drummers and air guitarists who were there from a musical standpoint and that’s fine too. So even intellectually it’s pretty hard to drop broad strokes. You know, we’ve noticed that when we do those so radio online talk show, what’s that called Rockline?

Marc Allan: Rockline

Neil Peart: Several times when we’ve done that, for instance the questions do range from intelligent and provocative to down right insulting the Rush. So, you know, you can’t generalize. It’s a possibly, you’ve got a broad cross-section of almost a million people. I have to think, I asked myself these existential questions on stage sometimes when I’m sitting there thinking, first of all, why am I here? And why is the whole point of my life to play well in Fresno tonight you know, or whatever. But it is, you know, recognizing the fact that it is so that I judged my whole existence. My whole existence is focused on being on stage and Fresno and playing well. And then wherever we are, I look out at the audience and say, okay, here we are in Phoenix, or here we are in Atlanta or whatever, at least 10,000 Atlanta heights or Nashville or, you know, Cincinnati or Indianapolis or whatever. And I look out at these people sometimes I think, well why are they here? And what are they getting out of this, you know word I’ve been thinking of lately a lot with regard to art and entertainment is nourishing. What I can get out of a good movie or a good novel or something. And I feel nourished by it. So I started thinking about, well, what is it about this event of a rock concert, you know, is nourishing to them and on what level? So I asked myself those questions too but there really are no easy generalities. It’s just an interesting subject.

Marc Allan: Since it’s 20 years in 19 records. I wondered if you could, could go through the records really quickly and just, I mean I’ll give you the titles. You want one in chronological order and just a sentence or two about what you think about them.

Neil Peart: Yeah. It’s not really necessarily I can go in broader strokes than that. A pretty linear, upward climb as far as I’m concerned in learning the craft. You know, first learning how to play our instruments was the first four records really, you know we were concentrated truly on learning to play and the phones were vehicles, you know, right up really through the first six. So they, they were vehicles to experiment on learn how to play, handle time signatures and different sorts of musical changes technically. And then after that, we got interested more in songwriting from tape, Permanent Waves on that became of interest to us. And we concentrated a lot on that. And the musicianship then became into the service of the song, which was established. And then later in that in the eighties arrangements became a paramount to us.

Marc Allan: That would start with Signals would you say?

Neil Peart: For a while a little later, actually I would say working with Peter Collins on Power Windows and Hold Your Fire he was a really important catalyst to us in terms of arrangement and what could be done and what is interesting experimentally with trying different textures and different approaches to the rhythmic arrangements of songs. So that was the third stage of our post-graduate work if you like. And from then till now, I think we’ve been doing trying to do all at once. You know, the records that we’ve made since that time have been trying with varying degrees of success to juggle all those things at once. But our records are made so intuitively that they’re bound to be uneven. You know, there’s no way that I think we will ever create a masterpiece because we are so willing to experiment to give some new direction, the benefit of the doubt and put it on the record regardless. But there’s just not going to be a record where every song is a winner. I don’t think it’s not in our nature, and that’s, as it should be, I’m glad it’s that way. I could go through maybe the last 20 years, pick out one albums worth of songs that I think are truly, you can find pieces of work, but at the same time I recognize that a lot of times our experiments end up as blind alleys and other experiments lead us on to good things, so you just got to do them.

Marc Allan: It’s nice that people stick with you through-

Neil Peart: Exactly yeah. Without fans of course we couldn’t have that luxury of-

Marc Allan: It’s interesting to me that you say that the first four or five records were trying to learn how to play. I mean, that’s just, it’s incredible to even think that I mean, obviously at some, some abilities there or you wouldn’t have gotten a contract.

Neil Peart: There was a rawness inherent there, but I know for me, I don’t think I had started to master playing the drums until after 25 years. Right? Like, Oh I don’t underestimate what it takes to do that job well. And it told me in the last two years I started to feel a confidence of being able to handle, you know, the scope of of playing live for instance, which is the ultimate test and being able to control all the tiny little income and some smoothness and tempo and everything that it requires to do that it’s not easily won.

Marc Allan: Rush hasn’t really done this so much, but it seems like that the general movement in production is toward this big drum sound where the drums are really in the forefront, not just dance music-

Neil Peart: No, no it’s true in rock too, but what it requires of the drummer is to leave out all the small notes because of course they get lost, if the snare drum is a giant sound and the bass drum is a giant sound then if small notes are just going to be a muddy blur and that’s why I won’t go that way because I love small notes and I won’t stop playing them. So whenever I’m dealing with an engineer who wants to go that way, I say, well you know, you can have as much latitude as you want but don’t start losing, lose what I’m playing. So that’s an element of it too in our work that we can’t go too much in the noise area because we lose the subtleties and we are wet to the subtleties. Absolutely. So that’s one thing with that, and Counterparts, we found we wanted to make it a relatively raw, noisy record, but at the same time we weren’t willing to compromise our idea of a good sounding record, high fidelity and also the nuances of what we play on our instruments was not to be lost in some welterweight thunder of sound, You know? So there’s certain parameters that we just won’t compromise regardless of trend or whatever. I’m sorry to have to cut you off Marc but I’m going to call your colleague, and sometimes I think I don’t want to be late.

Marc Allan: Can I ask one other thing real quick? If music were this for another story I’m working on is music where like the stock market and you can invest in some young up and coming act, who would you pick?

Neil Peart: I wonder how young enough and coming-

Marc Allan: It’s entirely up to you.

Neil Peart: People are not like my friends inside at the the two big forces out of Seattle I definitely rate highly being Pearl Jam, Soundgarden real source of talent. We have an opening act out with us now Candlebox that I think are very good and have a lot of promise for the future. On the hip hop world I think US3 are a real I think the wedding of jazz and hip hop is born in heaven. And I think there’s a lot of possibility to be done there. And there’s another group I like out of Pennsylvania, I think they just have the second record coming up pretty soon called “Live” and I thought their first record was again a really promising to be great songwriting great musicianship and nice arrangements. You know, everything that you’re supposed to do. Good lyrics. So I really have hopes for them too.

Marc Allan: Okay. It says that a Primus is supposed to open for you.

Neil Peart: Yeah, they will be starting on the next round. So I think possibly by the time we hit Indianapolis we have up till now we had Candlebox for most of the time.

Marc Allan: Okay. Terrific. I appreciate it for our time. Thanks a lot.

Neil Peart: My pleasure man.

Marc Allan: Take care.

Neil Peart: Bye.