Neil Peart (Rush) 1990

A never-published interview with Neil Peart

I interviewed Neil Peart several times over the years and thoroughly enjoyed every conversation. In addition to being a great drummer, he’s a smart, thoughtful, articulate gentleman whose worldview extends well beyond rock ‘n’ roll.

This interview, recorded in 1990, was the first of our talks. Nearly 30 years later, I’m still amazed by his interest in visiting art museums and bicycling around the United States, his desire to become a prose writer, and his simple explanation for why Rush had been able to stay together for so long. (“We’ve retained not only respect but also affection for each other over the years.”) When we talked, Rush was touring behind Presto, its 13th studio album, so there’s also a lot of conversation about songs on that album.

A bit of context:

-Early on, we talk about—but don’t name—Rush’s first drummer. He was John Howard Rutsey, who left the group in 1974. He died in 2008.

-We also discuss the Meech Lake Accord, which would have recognized Quebec as a ”distinct society” in the body of the Canadian constitution. The accord ultimately failed.

For more about Rush, visit rush.com/band/, where the group’s credentials are laid out nicely: “More than 40 million records sold worldwide. Countless sold-out tours. A star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Officers of the Order of Canada. And that’s all very nice. But for these three guys, it’s all about the music, their friendship, and the fans.”

Neil Peart Links:

On Youtube:

Music History #04

Neil Peart Interview Transcription:

Neil Peart: Yes, hello, is Marc there please?

Neil Peart: Yes, hello, is Marc there please?

Marc Allan: This is Marc.

Neil Peart: Hi Marc, this is Neil Peart calling from–

Marc Allan: Hi. How you doing?

Neil Peart: Not too bad how are you?

Marc Allan: Good thanks.

Marc Allan: Good. Well, where are you calling from today?

Neil Peart: Hampton, Virginia.

Marc Allan: You playing there tonight?

Neil Peart: Yeah.

Marc Allan: Okay. How long a tour are you on?

Neil Peart: We went out in the middle of February and we’ll be ending the end of this month.

Marc Allan: Oh, so that’s not bad. You can see the light at the end of the tunnel. I want to start out by asking, did you happen to see the quote from Randy Johnson, the Mariners’ pitcher?

Neil Peart: No.

Marc Allan: Well, you know, he pitched a no-hitter the other night and he said, this is his quote, he said, “I just bought a drum set. I played it an hour and a half before the game. I was listening to Rush but I don’t think the drummer for Rush has anything to worry about.”

Neil Peart: That’s nice.

Marc Allan: Yeah, I thought you’d get a kick out of that.

Neil Peart: Yeah, that’s cool.

Marc Allan: Yeah. What was I going to say? What happened to the band’s first drummer?

Neil Peart: Ill health.

Marc Allan: Oh, really? What is he doing now? Is he still alive?

Neil Peart: Yeah, yeah, I just saw him last week.

Marc Allan: Is he friendly about it or-

Neil Peart: Oh, yeah, yeah, it was a mutual situation, yeah.

Marc Allan: Uh-huh. ‘Cause you would think that, geez, here’s a guy, I mean it’s not a Pete Best thing but it’s pretty damn close. He leaves a band and the band goes on to have a long successful career.

Neil Peart: Yeah, because it was mutual at the time, he wasn’t happy. He can’t regret a decision like that. Everybody faces decisions like that in their lives, where they look back and say, “Well, what if I hadn’t done that?” But the thing is, at the time, the circumstances said this is the thing to do so you do it.

Marc Allan: What is he doing now, do you know?

Neil Peart: Actually, he hasn’t played for years and years. He’s just starting to toy with the idea, he’s doing a bit of playing.

Marc Allan: Is he just in private business or something like that now, do you know?

Neil Peart: Yeah, actually, gym and bodybuilding predominantly as far as I know.

Marc Allan: Oh, really, okay. That’s kind of unusual. One other question about early Rush. When you first heard Geddy’s voice, what did you think?

Neil Peart: I don’t remember thinking anything at all really.

Marc Allan: Really? It’s just it’s such an unusual voice. I think the first time you hear it, yeah, you don’t think anything of it and maybe you get used to it after a while.

Neil Peart: It was the time too. In the mid 70’s a lot of singers sounded like that. It didn’t sound, I guess, as strange as come to seem over the passage of time. At that particular time, and also ironically the reason his voice ended up in those registers was because of the technological limits of those days. And the reason why a lot of other bands’ singers became very stentorian was because amplification. When they’re playing in basements and clubs and stuff it was so difficult for the singer to be heard because all the guitar players had 100 watt Marshalls and the singer had the little 50 watt PA. A lot of times those singers of that time were driven that way just getting the voice to project over all that noise.

Marc Allan: All right. In his quieter moments, do you guys play acoustically and sit around and work things out that way? Does he sing in different registers?

Neil Peart: Oh, of course, yeah. Part of the great thing is having a register that wide and a lot of times in our songs too, he sings in normal register and pushes himself up higher just for the musical power of it and the vocal power of it and also because he’s able to. Because his range is that broad. As I’m told, before I knew him, he used to sing a lot in a… Do you know who David Clayton–Thomas is?

Marc Allan: Sure.

Neil Peart: I guess, apparently in the early days that’s what he used to sing like.

Marc Allan: That’s a pretty wide range.

Neil Peart: Yeah.

Marc Allan: Wow, that’s very interesting. Let me see, on to… I guess we’ll go on to the new album for starters.

Neil Peart: We’re just leaping 20 years ahead.

Marc Allan: Yeah, for right now let’s just skip around. I have these questions but they’re not in any kind of order. I’m usually better organized but screw it.

Neil Peart: No problem.

Marc Allan: One of these record company deals that they send out, this Rush profile thing I was listening to and there’s a quote, Geddy’s on there saying that touring is probably the most difficult thing for him now ’cause it’s basically two hours of performing and 22 hours of doing nothing or just going stir crazy. How do you handle that after so long? Also, why do you want to handle it after?

Neil Peart: Yeah, that is a good question there. Both of them. It was a very difficult decision to make this time, whether to tour or not, and particularly for me because of that factor. There are lot of things I’m interested in life and a lot of goals that I want to pursue and not many of them can be done while you’re moving around every day. So I was very reluctant to think about touring, committing six months of my life to basically doing one thing. It’s what you have to recognize about touring is that you’re not really creating, you’re recreating. It’s like the old joke about the person that says they have 20 years experience when they have one year of experience 20 times. Touring is like that. You have one night’s experience, 200 times over. It is definitely recreating the same thing and the accomplishment factor at the end of it is dubious. In the early days it was more measurable and at the end of a tour I would feel accomplished that I learned a lot and I developed a lot during that time just by playing every night. And by the band playing together it was good for us as a band but at a certain time you tend to peak out in your potentiality. I felt that learning curve getting shallower and the increments of improvement becoming less measurable. Consequently, the satisfaction rate was less. I always feel too, for a band, playing live is the essence of it. It is what makes a band a living breathing thing is getting out in front of an audience and playing live with all the risks and the spontaneity and the immediacy of that. And the fact that it is once night is a microcosm. Each performance, in spite of the fact that it’s part of a chain of them, each one is unique and each night when you go up the stairs to the stage it is a feeling that, okay, tonight I’m gonna do it right. The perfectionist aspect of it is at every show. In fact, Geddy and I were discussing once that the pressure of a show releases at the first mistake. The first time you make a little inaccuracy or something that you don’t like goes by, in a sense, you’re free. Because for the first few songs everything goes well and you’re playing really well and you’re thinking, “Okay, this is it, this is it, this is gonna be the perfect night.” And the first time the little flaw comes out that’s when you’re free. Not that’s upset it, then now all I have to do is play as well as I can. I’m not aiming to achieve that perfection anymore. There are a lot of funny little aspects of playing live that become a very real part of your life night after night obviously. But the main factor was that I wanted Rush to be a living, breathing thing so I thought, “I really don’t want to tour but I want Rush to be a touring band.” in that kind of a context it was the only thing to do. The only thing worse than not touring was, Or the only thing worse than touring was not touring in my mind. That was the genesis of my personal decision to do it. And as far as how you deal with that is, I kind of set myself goals to achieve during the tour. I figure the tour’s there and the shows will take care of themselves as long as I keep the right attitude when I walk up those stairs every night. So they can be used. For instance, this tour I set out to learn something about American art. And I figured that could be my mission. So in every city if I have an afternoon free or a day off or something I’ll go to a local art museum and browse through the paintings and try to learn something about it. Because I didn’t know anything about it before. So it was a gap in my knowledge that I wanted to fill. And it’s been very satisfying.

Marc Allan: Wow, that’s-

Neil Peart: I’ve been to 20 odd museums in different cities on this tour. And have acquired quite a lot of knowledge about it. So that’s satisfying. In other tours I would decide that I wanted to see more of the real United States. So I carried a bicycle with me and I’d go out, again, on days off or an afternoon before the show, and ride around the city or the country side and see some of America that I’d been missing for the last 15 years of traveling. I kept thinking, “Well, look, I’ve traveled around “the United States for all these years.” All musicians like to think they know about the places they’ve been to. But, of course, touring is not like traveling anymore than being a tourist is like being a traveler. I set up to change that too. And that’s really served me well. That I always have an escape. As I talk to my bicycle sitting here. Any time I want, I can get on it and go out and be independent. And also in the secondary benefit of it is I have been exposed to the real America. And the real people in America, too. Not just fans. And not just promoters. And not just airport people. Just get out and ride around and look. And think about what I’m seeing and why it is the way it is, and all of that. So, it’s very refreshing and it’s also very stimulating to have that kind of an experience. So I tried this time to incorporate touring with that. And I always have an agenda of reading where I bring out a carefully chosen selection of books that I really want to read. And Sunday’s great because of the Sunday New York Times and I have the crossword puzzle. All these little things add up to other levels of enjoyment and accomplishment that a tour can provide.

Marc Allan: So you’re like a real human being on the road. Or as close as you can be.

Neil Peart: Well that’s the aim of it too, and that’s an incisive kind of comment too when you think about it, it is a dehumanizing atmesphere. You’re traveling around in a very isolated and very unreal situation where people are constantly reacting to you in a very unreal and essentially inhuman way. They’re looking at you as an object, rather than a person. And that gets very alienating. And of course the history of rock us full of those kinds of stories of alienation and the prices that people have paid for that alienation. And people as intelligent as Roger Waters have been able to articulate it for everybody else, too. But to the people at large, it is glamorized and mythologized and seems to be some kind of dream world as if you were traveling around in a fantasy castle and the reality obviously is far different than that.

Marc Allan: Is that where the line “living on the lighted stage approaches the unreal” comes from?

Neil Peart: Yeah absolutely.

Marc Allan: Well it makes perfect sense really.

Neil Peart: If you let it. That’s the choice we made early on is that no, we weren’t going to do that. And part of the good thing for us is that we did come up slowly in a sense. Our success came to us by slow degrees really. So we were able to watch other bands and how they responded to it, and how they acted, and if they chose to play that role and the price they paid for it. And we realized that a lot of the bands that we opened for, some people could play that role successfully because they were strong enough and because they were cynical enough. But when we looked at other people who were more sensitive or more unstable, they got lost in it. They played the role and became the roll. A part of the thing that superconductors about on the new album too, is that the role becomes the actor. And we saw that happen to so many musicians. They went out and played this larger than life goal, and soon the perceive themselves that way and if they were unstable then that leads to the substance abuse and the tremendous unhappiness that even success can brin people to.

Marc Allan: Yeah, you know you’re putting it in a way that I’ve always thought about it, but I’ve never heard anybody articulated it that way. So it’s kind of nice. Because that’s so true. People do, they look at themselves and if they’ve been on the road for a while and they’re getting good audiences and they’re selling lots of records, they become so incredibly important. Or at least in their own mind.

Neil Peart: At least in their own mind.

Marc Allan: Yeah.

Neil Peart: I mean there are really two ways you can look at that kind of adulation I think. You can either be embarrassed about it, as I am or you can embrace it, and say, “These people love me? I love me too!” Well then you walk back out the backstage door and you jut want to stand there with open arms and basque in this undulation because you think you deserve it. Or if again, like me, you don’t think you deserve it, then you’re just embarrassed and you want to run away and hide, you know? But I think although they both have their prices, I think the latter aspect is far healthier in the long run.

Marc Allan: When you’re out and you’re in art museums, et cetera have people run into you and know who you are? Or is that–

Neil Peart: I mean, no, and again that’s very much a question of body language. I had a funny experience in Washington when I was going through the national gallerias and I kept being in the same room with this guy who was wearing a Rush t-:shirt from the concert the night before, who had just seen us, but it’s the way you carry yourself, again, you don’t make eye contact, and you look down and you look away, and you look at the paintings, and the guy never noticed me.

Marc Allan: Yeah, that’s pretty funny.

Neil Peart: It’s the same walking down the street. If you make yourself noticeable, then you will be noticed. But if you try to be anonymous actively, then a lot of times you can achieve it. And you pick up little tricks along the way. Pat Travers once taught me something years ago when he wanted me to come out to his bus after a show and hear something he was working on, and I said, “well look, there are 5,000 people out there, how are we gonna get to your bus?” And he said no no. Just put your head down and move fast. And he was right. We went right through that crowd and nobody noticed us. so it is tricks you learn along the way. Again, if you wanna be that way. If you wanna protect your anonymity then you soon learn how to. Just how not to be noticed and how to be anonymous. So you might walk up to that guy in the national gallery and say, “Hey, nice t-:shirt, I saw them last night. Weren’t they great?”

Marc Allan: Hey man, did you like the show?

Marc Allan: That’s good. It’d be funny to do that you know, ‘case if the guy recognized you, he’d flip. And if he didn’t, you’d get a pretty good sense of what you’re average fan was thinking.

Neil Peart: Yeah, but unfortunately when you’ve been jumped on constantly for years and years and alarm goes off when you see a thing like that, and all you wanna do is avoid it as much as possible. Obviously you can’t escape it all the time I mean when you’re in a city playing, people expect to see you there. And when you go up to the gig to go to work, or when you come out leaving work, you’re kind of in a context in which anonymity is hard to come by. When you deal with that all the time, when you’re away from it, for me anyway, I try really hard to preserve the distance.

Marc Allan: Yeah, I always think that the guy who has the best life is the guy who owns Walmart. Because he’s a billionaire, and no one knows who he is.

Neil Peart: Yeah! I always thought the same thing. Having wealth, and freedom, and Independence and all that without fame is far preferable, but then there are people unlike you and me who don’t feel that way. Who want the fame, and would rather be famous and poor then rich and unknown. And that’s an aspect of human nature that you have to deal with, and again, I see that in a lot of musicians too. Some of them, the affirmation of people loving them is much more important than any of the other parts of it. That’s what they basque in, that’s what they in some cases got into it for. A lot of musicians will tell you, “well I got in a band to get chicks.”

But now as I found, it expands into a bigger syndrome and their personalities, and that desire for approval and admiration and all that becomes their whole reason for being. And again, it becomes a very unhealthy conflict I think in a person, just to base your whole life on what other people think of you for a start.

Marc Allan: On a couple of the songs, well first, back to the profile disc, you mentioned on there about chain lightning, and you explain that song and I was wondering, how old is your daughter?

Neil Peart: 12.

Marc Allan: 12, okay. Is War Paint written for her?

Neil Peart: No.

Marc Allan: No? Okay.

Neil Peart: No, in fact that’s written for, in a sense all ages. But I was thinking more of people who are supposed to be grown up, but are still acting that way. I set it in the imagery of adolescence, but I was definitely thinking of, and my theme arose from thinking of people of my own age who still act that way. Vanity is the great liar, you know? And I see that so much, where people that I’ve grown up with and if they haven’t done well in life, it’s all somebody else’ fault. And that kind of thing, that they’re just waiting to be discovered, and people that have done will are lucky and they’re just unlucky because they just haven’t. All of that, it really just comes down to vanity at the root of it, and that’s all the stuff I was thinking about, and then I just chose to use adolescent imagery to express it.

Marc Allan: See my reading of it was maybe your daughter was at an age where she was ready to go out, and it was kind of like a fearful father song.

Neil Peart: No, actually, not at all.

Marc Allan: Okay. But I guess people get out of I what they, you know. They see what they wanna see, right?

Neil Peart: Yeah, I have no problem with that at all, but there are a lot of songs on this album particularly where I think I’ve tried to learn in lyrics, to project myself into a situation and express it as if it were autobiographical. But in fact, most of the time, it’s not. A lot of the little vignettes, songs like Presto or Hand Over Fist, they express little, what seem to be dramatic situations and they seem to be true, but in fact they’re not. I made them up to express a point, you know. I made them up to illustrate something I guess in a literary sense. But no, I’m lucky my daughter’s not superficial, so I don’t have those fears.

Marc Allan: Yeah, or the way I just looked at it was here’s a girl who’s growing up, wants to grow up a little faster than she should.

Neil Peart: Right, well I understand that, it’s certainly not a bad reading at all. But no, in the context–

Marc Allan: The wrong reading, but not bad.

Neil Peart: No not even wrong. I think the essence in it is you try to allow for all of those. And one of the reasons I chose that imagery was certainly to allow that interpretation and part of the idea of reconciling the universal ideas with the personal ideas is to try to be a little bit either ambiguous or ambivalent I guess is more the right word. Just trying to allow for both of those interpretations and as long as there isn’t an opposite one available, you know which happens in some songs. There was a song of ours called Middle Town Dreams on Power Windows, and it was about the power of dreams, and how about people at any stage in their lives can go out and do something. You know, can go out and make their lives true. And make their dreams come true. And to the cynical people though in the world, they read it as a cynical song, the fact that these were all washed up people who were tragedies of life, ad in fact in each case of the characters I drew in that song, I did draw from life. And I talked about, or I thought about a writer like Sherwood Anderson, who, when he was 40 years old, decided to stop being an insurance salesman and become a writer. Or Paul Gauguin, who decided to stop being a stock broker and become a painter, you know? I was thinking of real people like that in the song, And expressing the fact that at a certain point in their lives, they just said enough. I’m going to go back to the dreams that I left behind and make them true. But a lot of people read the exact opposite thing into the song and thought I was being very cynical about how these insignificant little people were failures and tragedies. When I meant exactly the opposite. Here are people that would be perceived as being small who went out and made big dreams come true.

Marc Allan: One of my favorite lines on the album, and I really think that this is the best Rush album that I’ve heard, and it’s amazing to me that you guys can keep making good albums and just because I would think that creatively you start to just get tired of it. And I would think you’d get board with the whole process. But, anyway.

Neil Peart: No I think it’s more dangerous for a single artist than it Is for the three of us, you know.

Marc Allan: Anyway, the line I like is from the title song, where you say, “I radiate more heat than light.”

Neil Peart: Right

Marc Allan: And I wondered, what do you think about Rush? Does Rush radiate more heat or more light?

Neil Peart: Hopefully a balance of the two. Actually the germ of the line is actually kind of interesting. During the American presidential debates I got very interested in it all. I love debates anyway, but the way that they were all set up and the whole stage managed show business of it and all that. So I was faithfully watching the presidential and the vice presidential debate, and coincidentally in Canada there was an election going on at the same time, with the same kind of debates among the leaders of the parties and so on. But at the end of one of the American presidential debates, that line was used, I think by Dan Rather or somebody, saying that during the course of the debate created much more heat than it did light. And I thought that was a beautiful image, so I wrote that down and kept it.

Marc Allan: That’s good. Do lyrics come to you like that from other sources?

Neil Peart: Oh definitely so. That’s why I keep a notebook in hand ad from the newspapers or from television or something somebody says, or a passage in a book that I’m reading or just a combination of two words that occurs to me when I’m riding my bike, all those kinds of things, I often come back from a bike ride with my map covered with little notes.

Marc Allan: So you’re always working, even if you’re enjoying yourself.

Neil Peart: Yeah, that’s right. I read a great quote once, a writer, saying that the hardest thing for a writer’s wife to learn is that when he’s looking out the window, he’s working.

Marc Allan: That is great, that’s a good line. I’ll have to remember that, my wife says what am I doing, you know. Let me see, um. Since you were talking about politics, I was just in Canada a month ago, and found the Meech Lake Accords quite interesting, And really the entanglement of it all. What do you think is gonna happen, and what do ya hope happens?

Neil Peart: Oh, it’s just so confusing. It’s as if the United states had had no constitution and no bill of rights for 200 years you know? And suddenly today, President Bush and all his buddies decided to sit down and ratify a constitution and a bill of rights. You can imagine what kind of chaos that would lead to. Oh yeah. And to have it in place, and that’s what Canada faces. Basically we had no constitution accept that which tied us to Britain, and it was so called repatriated eight or nine years ago. But still, nothing was done with it. It wasn’t drawn out, and it wasn’t agreed to and all of the premises of life for instance weren’t put down the way they are in the American model. So that’s basically what they’re trying to do right now. And trying to do it in this point in history with so many factions and so many waring points of view and especially in Canada, with the Quebec situation too, oh, its jut a big mess.

Marc Allan: I wonder, do you think Quebec can leave, and will leave?

Neil Peart: Not in practical terms, no. I spent a lot of my time in Quebec, so I’m very sympathetic to the Quebec cause, but in real terms, one of the pundits said that if Quebec wants to leave, fine. Just tell them to pay off their portion of the national debt and they can go. And that right away makes it an impractical situation.

Marc Allan: Yeah, we were in Prince Edward Island, and the, I don’t know who it was, Buchanan, what is his job there, title there?

Marc Allan: Premier?

Neil Peart: Premier, yeah. And He had made I guess and off hand comment that there wouldn’t be anything left for that part of Canada to do but to join the United States, which of course everybody just went berserk about, they didn’t want anything to do with us. By the same token, I asked people about that, and they said well, you know we like our national health insurance and some other things and they said by the same token, the United States wouldn’t want us because we’re the poorest area of the country.

I’m not a nationalist by any means, in fact I would quite happily sign a petition to join Canada to the United States because I’m equally at home here in the States as I am in Canada and I don’t perceive a lot of differences really although that would have me lynched if I was saying this in Canada, but you know, I think all of that is just kind of stupid. And so much of our election hinged on the free trade issue too, which has completely died down into business as usual.

Marc Allan: Well I think that biggest difference that I perceive is just the general awareness that Canadians are just more aware of the United States, then the United States is of Canada.

Neil Peart: Yeah, but that’s strictly a question of degree too. There are 200 million in the states, and 20 million in Canada, It’s a big neighbor to us, where a big neighbor in humanistic terms to us, where the reverse doesn’t really apply. So I don’t have a problem with that. And the same thing in Canada. We learn a lot about British history too. What’s the point of it? The only reason is that historical, you know, tying of the apron strings, really. Although we don’t learn about African history, we don’t learn about Chinese history, so it isn’t really objective either. The fact that Canadians know a lot about the United States well so they should. So anyone in the world should know a lot about the United States as far as I’m concerned.

Marc Allan: Well, I think there’s some truth to that. Now we just tend to have very little idea here about what goes on in other countries, you know. Unless it’s the country of the moment.

Neil Peart: Yeah, well so does everybody else. I was doing some writing about Africa recently and I came across a tragedy that took place in the country of Cameroon where a bubble of volcanic gas came out of a lake in Cameroon and killed 1,700 people in their sleep. Or whether there’s an earthquake in China and it kills tens of thousands of people it might get a few column inches on an inside paper, but if there’s an earthquake in San Francisco, you know, with 40 people killed, you don’t hear about anything else for weeks! And Canadians are exactly the same. If there’s a murder in Barrie Ontario, our newspapers are full of it for months. But you know, again, if tens of thousands of people are killed by a horrible tragedy in China, nobody really cares. It’s a tribal thing really, and the farther away from your tribe something happens, the less important it seems to be. That’s just human nature more than a national attribute,

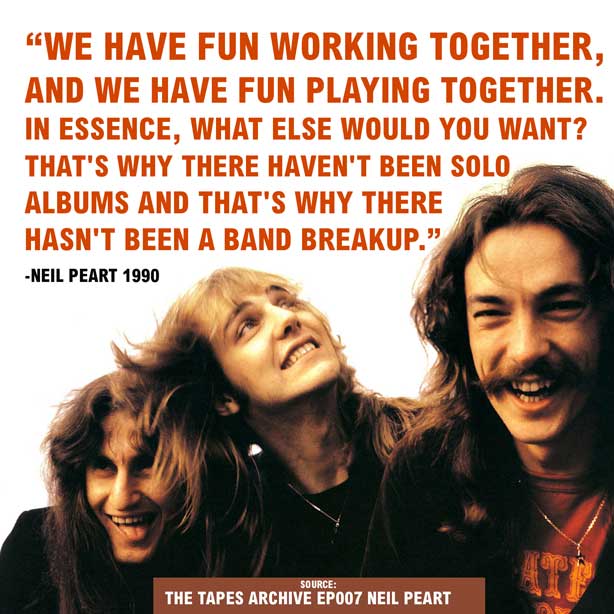

Marc Allan: okay, I had two other things I wanted to ask you. One is, what do you think it is that’s kept the band together for so long?

Neil Peart: As trite as it might seem, I’d say friendship. Jut the fact that we’ve retained no only respect, but also affection for each other over the years. And there are many factors that contribute to that too in terms of the kinds of people we are and the way we relate to each other the different kinds of personalities that we can each complement, all that’s a part of it. But essentially it does come down to just being friends and respecting each other. And satisfaction, I suppose if we weren’t satisfied with the work that we did together that would end it all regardless of friendship. But I think as I outlined in the Scissor Paper Stones story, but at the bottom line of it we have fun together. We have fun working together, and we have fun playing together. In essence, what else would you want? That’s why there haven’t been solo albums and that’s why there hasn’t been a band breakup, and that’s why there haven’t been crises and scandals in the papers, it’s because those immutable things are those matters of longevity as far as job satisfaction and good interpersonal relationships to put it in corporate terms. Some kinds of things have survived, you know?

Marc Allan: But you know in bands that have existed for as long as Rush, and how many have existed for a shorter time you know the members just hate each other.

Neil Peart: Oh yeah. Much more than people perceive, and you probably have more insight into that than most people do. How people go to a concert, and they see the band playing on stage together, and then at the end of the show they see them all bow and hold hands and all that stuff and then at the end they go to their separate dressing rooms and get into their separate cars and sometimes even stay at separate hotels. I saw the live video the Police did just near the end and I realized that during the whole course of like an hour and a half, they never looked at each other once. There was no interaction between the guys in the band. But not only that, there was no acknowledgment of each other, it was three guys on a stage play, not together, but playing individually under one name. So yeah, that I think is the reality far far more than people have any idea.

Marc Allan: So you must have felt very good when you saw something like that, because you’re a three person band–

Neil Peart: Yeah, being in the middle of a tour and knowing the kind of interaction the three of us go through on stage and off, where that just could never be for Getty and Alex not to be punching each other around at the front of the stage or chasing each other around and all the silly things that we do to entertain ourselves on stage, its hard for me to imagine working without all of that. To me it’s such a part of what we are and have been that being in the middle of a tour and seeing sort of an object lesson like that of the opposite, it makes you feel very fortunate, and I just feel really glad that this band happened to have worked out interpersonally the way that it has.

Marc Allan: That is really nice. You had mentioned earlier that you had some interest in some things that you might not have pursued otherwise had you not toured. What kinds of things are you doing with yourself?

Neil Peart: Prose writing interests me enormously. Just learning about it and trying to develop a skill of putting what you think into words versus kind of a very different discipline. So working on lyrics is a very different mentality than thinking in terms of sentences and paragraphs and the structure of chapters and all of that, so prose is something that I’ve studied by reading. Obviously all of the greats that have done it, but also by trying to do it myself. You never know how hard something is until you try it really so that’s something that has absorbed me, more as a hobby, really. I don’t try to see myself as some of the great Canadian novelists by any means, but it’s something I really wanna know how to do. It’s a skill that I want to develop. So I spend a lot of my time outside of the band working on that in one area or another.

Marc Allan: So do you have a work in progress now?

Neil Peart: Always, yeah, but I hate to dignify it that much because I don’t have aims to publication or anything like that. It’s just to me an apprenticeship in a way that I keep turning out pieces of work just to teach myself things and then I put them aside and six months later I look at them and see that I’ve progressed from them, so it’s lik taking on anything new. The learning curve is steep. Where with music after having played drums for twenty-odd years now, the learning curve is very shallow. You know, I’ve learned a lot, and practiced a lot, and really put a lot of time and effort into learning the craft of it, so learning new things is partly not that appealing, and also partly futile. To spend six hours a day everyday learning how to do a faster paradiddle seems pretty much irrelevant to me now. Where I can spend six hours a day, day after day, learning how to put sentences together and it is very satisfying. Because it’s new, and because the improvements so measurable. I can understand what I’m learning and read a lot of other peoples’ ideas of how to do it, and try to apply them and all of that. So I don’t like to dignify it too much consider that I’m a writer by any means, but I’m trying to learn how to.

Marc Allan: A couple other things, since CD’s have become dominant, has that changed at all the way you have worked the way you have recorded, the way you’ve done your album cover art, anything?

Neil Peart: Yeah, it’s actually been a pretty wide ranging change of things. But suddenly the record which we always considered sort of the standard medium for all years past, is no longer anymore. In fact it’s definitely and endangered species. So certainly in the terms of cover artwork you’re trying to deal with something that can be perceived and dealt with in a 3×5 piece of cardboard in a cassette box, or in the 5×5 CD box, or 6×6 or whatever it is. That’s part of it, but also in terms of the music. The division between side one and side two for instance was always a really important part of the writing order to us, you decide sort of the progress of side one, and what song should end side one, and then a lot of times the song that began side two would be an important consideration and thee would be a flow in terms of the dynamics of it, almost comparable to a live performance that two sides really made much more interesting and much more workable, where when you’re dealing with a CD, where it’s essentially all one side you have to rethink that too. But the other perimeters of time are very positive. Having more time to work with, it hit us on both of the last two records in terms of the live album, we knew that we wanted it to be a single CD, because we weren’t about to ask people to pay a ridiculous amount of money to buy two CD’s just to get a couple of extra songs. So it limited our choice of material in wanting it to be I forget, 72 minutes or something like that, it had to be to fit on one CD. But in terms of the Presto album, it set us free. Because we weren’t worried about 40 minutes being the ultimate length of a record or the ideal length of a record, 20 minutes a side. Suddenly with a CD or a cassette the limitations were much greater, so we could have more songs and thus spread out more stylistically. ’cause when you’re judging individual approaches a lot of times as more songs get written, you’re thinking about what’s been written already and stylistically what you would still like to cover. So having more time to work with allows you to get I think more into the corners stylistically and to bring out things that are maybe a little more eccentric than you might have bothered to put into a 40 minute piece. So I think yes, the difference has been pretty evolutionary.

Marc Allan: In the show that you’re bringing to town in a couple of weeks, is there anything special going on? Anything new? Anything different that people will be interested in seeing? I mean long timing Rush fans, you know. ’cause you guys seem to have a very solid base of fans who just, they’re devoted to the band, etcetera, and I just wondered what’s new for them?

Neil Peart: Yeah it’s always really hard to answer because you don’t like to sort of pump out the hype in once sense, and in another sense you hate to spoil the surprise. But in broad parameters at least, we did rethink it from the ground up, in terms of choosing the materials we would play, both new songs and particularly old songs. You know, which old songs we would continue to play and which old ones we haven’t played for a while that we would bring back. So I think the substance of the show is very much different than it has been in preceding tours. As far as the presentation goes, again, we try to rethink from the ground up, and not do anything just because that’s the way we did it last time. SO the whole visual presentation of, for instance, rear screen videos have always been a big part of our show, but a lot of those, they can tend to become cumulative in the sense of playing the same songs every tour you tend to show the same films to accompany them. So again, we threw out that presumption, and dropped a lot of the films that we’ve used in the past and created some new ones, both for new and old songs. And sometimes kept the songs but dropped the film, you know, just to keep something fresh about it, and also to avoid staleness I guess in the opposite side. So there was a big rethink right from the ground up and I think the show is very different, but at the same time, we’re still drawing from the same well of material and a definite healthy balance in the course of a two hour show between old and new stuff. And there’ll be some surprises and songs maybe that people haven’t hear for a while if they’ve seen us live from tour to tour that will be a pleasant surprise to hear.

Marc Allan: Do you play The Pass?

Neil Peart: Yes.

Marc Allan: Good. ’cause that’s my favorite one.

Neil Peart: Oh good!

Marc Allan: I really like that. I get drumming, there are just some little intricacies that I really find attractive, but I think the whole song is just great.

Neil Peart: Oh that’s interesting. It’s always nice to know which songs people respond to the strongest, but it’s funny that in addressing the drum part particularly, Is that it’s essentially so simple, and through Modern Drummer Magazine I got a letter complaining in fact, that thought the drumming on the song was too simple. And it just was so stupid because I spent more time on individual parts for this album than ever ever in the past, just constantly refining down each little element of what I was doing and why, and some of the passages took more time individually to come up with than any of the more overtly complicated stuff we’ve done in the past. But part of the essence of that, or part of the essence of any kind of proficiency I guess is making the difficult look simple. So if you spend all of the time, like The Pass, the drum part took me days of work to refine down to be exactly what I wanted it to be. But in essence from a technical point of view, it’s relatively simple to play. So consequently from a superficial judgment of a young teenage drummer, who just wants to see Flash, it seems simple, but it’s the old thing of if it’s easy to play that must mean it was easy to think of. Which of course is not the case. And I remember when I was starting out young guitar players would learn Jeff Beck guitar solo and then think, “hey, I’m as good as Jeff Beck.”

Marc Allan: Yeah, try writing it, you know? Try creating it.

Neil Peart: The contradictions in that are obvious, but they’re not obvious to a beginner. You know, you think if you can play it, you could have written it. And I think that’s probably true of all the arts. It’s all a constant criticism. Painting, you know, “oh, my kind could paint that.”

Marc Allan: When I was especially in high school and I think we took this extremely seriously that we’d have long running arguments weather Jimmy Page was a better guitar player than Steve Howe and such. The one thing that we ever agreed on was that it came down to writing, and who wrote better songs and that’s just–

Neil Peart: And I was glad to realize from the beginning too was really an important insight that I had in my young years is the difference between taste and quality. That I could recognize for instance Eric Clapton I was always thought was a good guitar player but never really liked his guitar playing. Whereas I know there’s a lot of music that isn’t that great technically and a lot of reggae and a lot of R&B and stuff but I still really like it, and just learning that difference to say, well, this isn’t that great, but I don’t really like it, or this is great, but I don’t really like it it’s a really important distinction to make, but a lot of people never do make it, they think if they like something, its great. And if they don’t like it, its shit. It’s a very simple equation, but of course in any kind of art, it doesn’t really apply.

Marc Allan: I wanted to leave you with this observation, and that is, people, but I think Rush is a good example you know, where there are people who, I mean I tell people I like Rush, and they kinda cringe, sorry. And I’m sure you know how it’s just a fact of life.

Neil Peart: Oh yeah, sure.

Marc Allan: People ask me why and I think after this album I’ve got a really good idea of why. And the reason is, because I’m 31 now, and I think Rush is playing the kind of music that even though it’s the 90’s, there’s still a lot of throw back to the 70’s. And that’s when I grew up, and you’re playing the kind of music that I like. But I’m older now, and I’m smarter now, and I can enjoy it and I don’t have the hassles of teenage life to contend with. So that’s–

Neil Peart: That’s a very good observation actually, it’s on that people often miss, is that we are still writing for our peers, and a lot of people of your age and my age, I’m only a few years older than you, a lot of our peers have grown out of music and not loner really have any interest in it. So they don’t really come into the equation. But guys like you and I who grew up through the 70’s and loved all those bands and that our lives have gotten bigger, they’ve gotten broader and our interests have gotten more subtle and the parallels that we draw to life are more interesting now and that’s all the stuff that I think has changed our music too, and we’ve grown up with it and when I look out into the audience like last night and see a few bald heads and a few mustaches, and a few couples who have obviously had to get a babysitter to come to the Rush show, I think yes, those are the kinds of people that are most gratifying. I mean it’s nice to have people there that weren’t even there when we started playing together. That is very gratifying in another way. But in a sense it’s deeper somehow, to have grown up with somebody. When I get letters too from people that got into our music in college, and now that they’re out in the world, they’re set designers or writers, or scientists, or whatever, but Rush is still a part of their lives. And I think of all the tributes, I think that’s probably the highest one. That you stayed part of someones life through all of the changes from teenage to adulthood through all the changes that that engenders.

Marc Allan: Yeah and that you’ve been able to change also. I mean, obviously you’re not playing the same songs. I mean there’s variety in your music. Its still there, I mean there’s still a hold. You know, I can hear a little Emerson Lake and Palmer or a little Yes, or something like that, and I think oh that’s good, cause you know those guys, they’re either not doing it anymore, well in the case of Emerson Lake and Palmer or in the case of Yes, they’re not doing it nearly as well, so.

Neil Peart: I understand what you mean. Anyway, well, when you’re here, are you gonna have the afternoon free to go to a museum? Or do you not know? ’cause our art writer’s sitting right next to me here and I was gonna ask him if there’s someplace special that you should go to see.

Marc Allan: Right, well I have an excellent little guide called Art in America Museum Guide, and it gives all the art museums in the United States, and what traveling exhibitions they have and what their hours are and what their address is so it’s been kinda my bible this tour.

Neil Peart: Oh, okay. Whenever I have a day in the city, wherever it is I just look up what they have and then choose what to go and see.

Marc Allan: Nice.

Neil Peart: So I know Indianapolis is in there.

Marc Allan: Okay, then you don’t need our recommendation. okay. Well I really enjoyed talking to you, and I’m looking forward to seeing the show.

Neil Peart: Okay, thanks Marc.

Marc Allan: Okay thank you, bye.

Neil Peart: Good to talk to you, bye