Little Richard 2000

A never-published interview with Little Richard

In the interview Little Richard talks about:

- Who he really wanted to play him in the movie

- His desire that you understanding him

- Why he wore make-up

- If he considers himself gay

- Whether he ever wore a bra

- How he was the first African American to be on white radio

- What’s accurate and not accurate in the movie

- How his Daddy beat him

- And more…

Little Richard links:

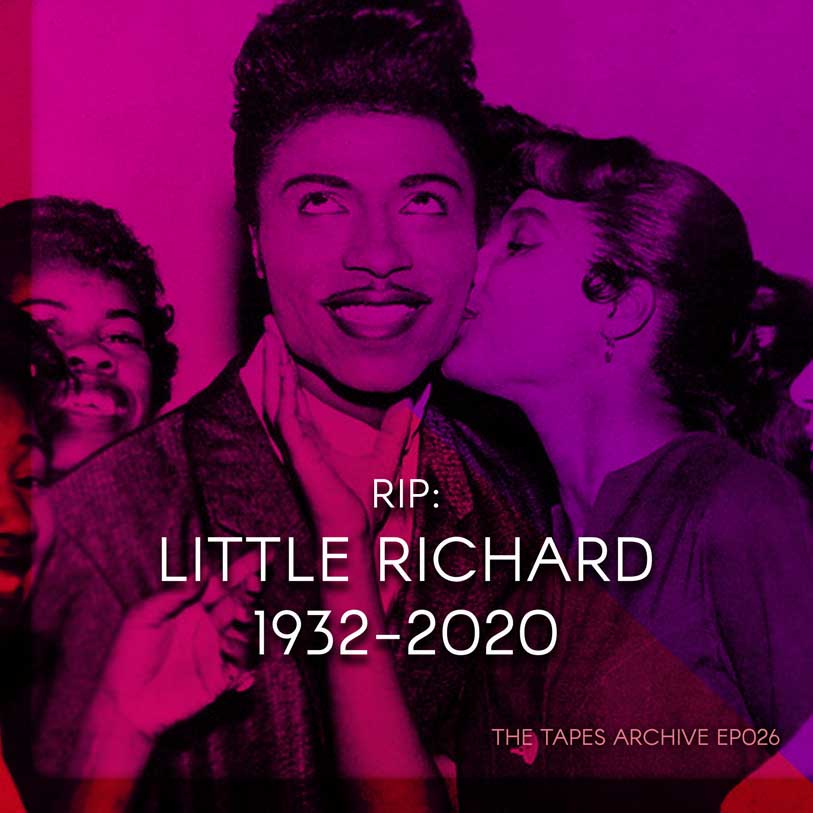

In this episode, we have one of the pioneers of rock and roll–the recently departed Little Richard. At the time of this interview in the year 2000, Richard was 67 years old and was promoting the TV movie based on his life called “Little Richard.” In the interview, Richard talks about why he wore make-up, if he considers himself gay, how he was the first African American to be on white radio, and how he discovered the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix and the Rolling Stones.

Watch on Youtube

Little Richard Article:

This is from February 2000. Incidentally, Little Richard inspired the best headline I ever wrote, on a story about the popularity of bamboo flooring:

This is from February 2000. Incidentally, Little Richard inspired the best headline I ever wrote, on a story about the popularity of bamboo flooring:

Wop-Bop-a-Lu-Bop (We Love Bamboo)

By Marc D. Allan

Little Richard wants you to watch the TV movie named after him, which airs from 9 p.m. to 11 p.m. Sunday on WTHR 13. “See the living flame and see history alive on the 20th” is what he says, his trademark “woooo” implied.

But in a telephone interview, Little Richard, the man, acknowledges that Little Richard, the movie, is a glossy, incomplete and sometimes fictionalized version of his first 32 years.

Unlike the movie character, for example, he’s never worn a bra. “Never have,” he says. “Never have in my life. Never have in my whole life.”

Also, while the movie credits Dorothy La Bostrie with completely rewriting the lyrics for Tutti Frutti, his first hit song in 1955, Richard says it’s giving her more credit than she deserves. “The part that Dorothy brought in was, ‘I got a gal named Sue/she knows just what to do,’ ” he says. “I had all the other parts of the song.”

And although the movie explains that he wore makeup to make himself look beautiful, the real reason for the overuse of Pancake 31 was to fend off angry white men who thought he was after their women.

“They thought you was trying to get women, and it wasn’t about that at all,” he says. “But when we wore the makeup, there wasn’t nobody intimidated. They thought you was in the gay life and you wouldn’t bother nobody.”

There’s more. His relationship with the Beatles (“I discovered them”) is absent. The beatings his father administered are downplayed. And he knew a woman named Lucille, but she was not his girlfriend.

He also wishes the movie showed him writing a song and that it detailed how record executive Art Rupe took advantage of him.

As he’s explaining this, and telling the stories as he remembers them, Little Richard’s voice fills with a bit of evangelical fervor. He peppers his speech with the phrase “you understand me?” and the thoughts come to him so quickly that he practically stammers.

“I didn’t have a lot of input in the movie,” says the man born Richard Wayne Penniman 67 years ago. “In fact, I didn’t have any input in the movie. I went on the set about three or four times. I was touring while they was doing the movie.”

He is credited as executive producer on this project but says “that’s a title thing. You know how that is.”

But even with all that, he likes the movie.

He likes the job done by one-named actor Leon, who played the title role. He originally wanted Prince to portray him, but he says Prince wanted to put off the project for a few years.

“I wanted him to do it now,” Richard says. “I’m 67 years old. I’ll be 68 this year. And I just wanted him to go on and do it.”

Mostly, he likes the idea of preserving for posterity his honorific as the architect of rock ‘n’ roll.

The sound, the energy, the excitement he generated — the “wop-bop-a-lu-bop-a-lop-bam-boom” — came out of his upbringing in Georgia, where you had “swing and sway with Sammy Kaye” for jazz, Muddy Waters for the blues and, of course, gospel music from the church.

“But there wasn’t no fat, uptempo stuff,” he says. “Kids want to dance. You know how kids create their own dances, but the music don’t fit? So I started writing stuff that would fit what we felt for that time.”

Tutti Frutti, he says, just came to him. So did Long Tall Sally; Rip It Up; Lucille; Jenny, Jenny; Keep a Knockin’; and Good Golly, Miss Molly — all hits from 1955 to 1958.

His wild sound broke through all kinds of barriers. He takes credit for being the first black artist played on white radio and the first to perform for largely white audiences. (He also was one of the first 10 artists inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.)

As for discovering the Beatles, his story is this: “(Beatles manager) Brian Epstein’s daddy had a lot of record shops and he brought me to Liverpool. He introduced me to these boys who had just got a group together. And Ringo had just came with them. So I took them with me to a club in Hamburg, Germany, called the Star Club. That’s where we started getting together.”

He admits he didn’t immediately recognize the star quality of the Beatles. “They sounded like four Everly Brothers to me,” he says.

But meeting the Beatles comes around the time Little Richard the movie stops. The movie takes us from his early years in Macon, Ga., through 1964 — seven years after he quit rock ‘n’ roll to devote his life to God and the year he made his comeback.

In many ways, things haven’t changed. He’s still religious — “I’m a Christian person and my life is in Christ” — and he still tours.

Actually, Richard says, there’s a whole ‘nother movie to be made of his life. “I want to see what the people say about this one,” he says, adding that he’d like to see a completely truthful account “because the truth is going to be told, anyway. And the truth can stand the test of time.”

Just as he has done. He often thinks about his contemporaries, people like Buddy Holly and James Dean, who died young.

“That’s the reason I wanted them to do this movie,” he says. “Because most people, they don’t get to see their movies. You understand me?”