Kurt Vonnegut 2000

A never published interview with Kurt Vonnegut

In the interview Vonnegut talks about:

- If technological progress has been good.

- His love for the ACLU.

- Posting the ten commandments in schools.

- If he believes in God.

- His affection for Indianapolis.

- Being captured by the Germans in WWII.

- And more…

Kurt Vonnegut links:

In this episode, we have American Author Kurt Vonnegut. At the time of this interview, Vonnegut was 77 years old and was in Indianapolis for an ACLU fundraising event. In this wide-ranging interview, Vonnegut talks about freedom of speech and censorship, civil rights and war, God and religion, ethical suicide parlors and dying.

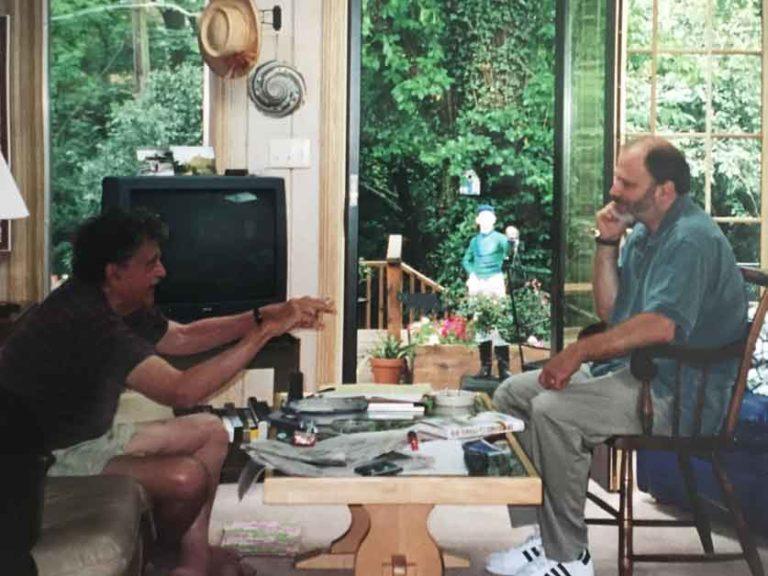

Kurt Vonnegut and Marc Allan:

The interview took place at his friend Majie Failey’s house in Indianapolis. I didn’t know she had taken this picture until she sent it to me. I have no idea what we were talking about at that moment, but I know what I was thinking: That’s Kurt Vonnegut! Right there!

Watch on Youtube

John Prine interview transcription:

Marc Allan: Ethical Suicide Parlor.

Marc Allan: Ethical Suicide Parlor.

Kurt Vonnegut: Uh-huh.

Marc Allan: Which you wrote about it in Between Time and Timbuktu.

Kurt Vonnegut: Yeah, yeah.

Marc Allan: It seems incredibly prescient now, doesn’t it?

Kurt Vonnegut: Does it? I guess. Yeah, no, I think it always would’ve been a worthwhile business to open. I think it would’ve been quite, ’cause people would’ve threatened you. If you don’t shut up, I’m going down to the green roof, to the purple roof, or…

Marc Allan: Then what made you think about that?

Kurt Vonnegut: Well, if you’re in my business, you’d just sit around all day thinking up neat stuff. Most people don’t do that.

Marc Allan: Did you ever think that something even close to that would really come true?

Kurt Vonnegut: Well, I actually, with everything I do has everything but originality, and what put me in mind of it was a German surviving the Second World War had said, what a wonderful business that woulda been in Germany at the end of the world, for Germans themselves trying to make sense of it.

Marc Allan: And now when you look at Jack Kevorkian, one of the best the logical extension.

Kurt Vonnegut: Well, we sent him a copy of the book of God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian, and got a friendly letter back. But I’m on his side, but I understand why it’s a bad idea, legally.

Marc Allan: You do? Why do you think it’s a bad idea?

Kurt Vonnegut: Giving permission, well, it’s during the ’30s, of course, euthanasia, the thing was going on as a political policy in Germany, is to getting rid of the weak and the insane, or whatever. And so that temptation is always gonna be there for someone who gets too much power and wants to get rid of enemies, or actually wants to clean up the society, according to his or her plight. Yeah, no, I–

Marc Allan: But when you wrote about it, you were writing about people taking their lives of their own free will, saying, well, I’ve had enough, it’s time to go.

Kurt Vonnegut: Yeah, no, I think it’s probably all right.

Marc Allan: You think that’s okay.

Kurt Vonnegut: Well, again, it has everything but originality. It is what the Greeks said was fair about life is if you didn’t like it, you leave.

Marc Allan: It must be entrusting to see some of the things that you wrote about long ago come true, or at least come closer to–

Kurt Vonnegut: Well, I’ve seen amazing things. I’ve seen lynchings stop. I’ve seen black people allowed to vote. Seen black people allowed to ride anywhere on a bus. Good work on that.

Marc Allan: Do you think you’ve seen problems?

Kurt Vonnegut: Oh, yes, in civil rights, you bet. And of course, Thomas Jefferson is the most popular of all our political ancestors, I suppose, writing The Declaration of Independence and all of that, did not see women or blacks as remotely equal to white men. And it’s quite something that the founder of the country with those particular attitudes, but those guys, and Voltaire, who’s a hero of mine, was a speculator in slaves as a commodity, knew it as some kind of commodity market and the great thinkers of, roughly, contemporaries of Jefferson’s, greatest minds of the times were operating on natural law, is what nature’s intentions apparently were. And it seemed to them that these black people were intended by nature to be servants of white people with better minds, and to that thinking. So it’s just perfectly natural, that’s what they saw in nature. And they saw if women are smaller, if I can easily beat up a dame, why, that nature wants that to be the case too.

Marc Allan: What about progress in other areas? Do you feel like technological progress has been good?

Kurt Vonnegut: Not necessarily. Ordinarily, if you’re going to build a factory, and this is quite new too and good, is there will be an environmental impact study of what the hell it’s gonna do to the aquifers, to the atmosphere, and all that. And there ain’t no such study made when something this radical as a creation of the most important person in any house, which is a machine, most influential person, which is TV. Well, as they say, you can’t fight progress and all that. But I’ve got a master’s degree in anthropology, that was my field after from the University of Chicago. And so, mess with a person’s culture, ’cause it’s a very permanent part of the personality, as far it naturally goes, the culture become a part of the person about as easily as you can fool around with his or her kidneys, or pancreas. But there are these radical surgeries that are being performed on human psyches but new electronic devices. I can regret the loss of human experiences, it’s so much about human beings and what they can do is now being discounted, and certainly for people of the past, there was a great adventure of people with any sort of mind of becoming, of finding out what this thing is here, right here, this, what’s inside our skull. And now, Bill Gates is saying, hey, you don’t have to become anymore, your computer is gonna become. Just wait till next year when you see what these computers can do. And so, there’s less to be proud of all the time as a human being. Still have disruptive of morale, but at the same time, the only response, certainly, not gonna have our legislatures outlaw TV or any kind of TV program, ’cause the first amendment absolutely leaves you powerless. Or with the computer mania, ’cause I have a son-in-law who’s almost disappeared into his, you know

Marc Allan: Into his computer?

Kurt Vonnegut: Yeah, had to pull him away from it and wake him up. But what you can do is you can retreat from it. I mean, we were talking about it, if you don’t like life, you can always leave. And if you don’t like all this technological stuff, you can put together some kind of life apart from it. And of course, the grotesque example is somebody who did that long before there were technologies like ours, was Henry David Thoreau. But he was protecting his soul and his personality, and it’s harder and harder to do that.

Marc Allan: You’re gonna come here in September, I guess, and talk about censorship.

Kurt Vonnegut: Well, talk about ACLU, ’cause I’ve been a lifelong supporter of it. I’ve been supporter of the ACLU before Indiana had a chapter for God’s sake.

Marc Allan: Are you surprised Indiana has a chapter?

Kurt Vonnegut: Not now, no. Years ago I spoke at some anniversary celebration of the ACLU in Louisville, and they were having some trouble with state cops who, I forget what it was, who were acting like Nazis. And they wanted a chapter of the ACLU in order to have a rational fight going, and plotted their chapter down there long before there was one here. I think there were efforts to have one here. But that’s even more of a border state than we are. But at the anniversary meeting where I spoke, and I’m just full of shit as usual, then had the founders stand up and there were about six of these sweet old guys, and I said, oh my God, there they are again. It’s in any town, it can be a dentist, anything, and decide it, got down to Bill of Rights must be enforced.

Marc Allan: How are you supposed to have, easily, people who are willing to give those away? To pass off their rights?

Kurt Vonnegut: Well, they take them away from other people, I assume.

Marc Allan: Right, they’ll take ’em away, and there are plenty of people who just say, okay.

Kurt Vonnegut: Well, I’m gonna talk about that some. I’ve talked about it before, but Thomas Aquinas had a hierarchy of law. There’s God’s law, don’t mess with that. There’s nature’s law, that’s what Thomas Jefferson saw. That’s why women and black people, or people of color, should be subservient to white intellectuals. And then there’s man’s law, and I say that the ACLU is always going to court with a deck of cards where the highest card they’ve got is the Queen, which is man’s law. There are all these people who are gonna play natural law tops the Queen, that’s the King and the Ace. And so, that happens again, and again, and again, and the people who wanna take away other people’s right to speak, speak their minds or whatever, are playing the Ace.

Marc Allan: You can imagine that the Civil Liberties Union couldn’t play terrifically in Indiana.

Kurt Vonnegut: No, well, they had political campaigns, national campaigns, forget Indiana. Talk about somebody as being the card-carrying member of the ACLU.

Marc Allan: But you see it, obviously, as a very good thing today.

Kurt Vonnegut: Yes, of course.

Marc Allan: The most recent case here has been about posting the 10 Commandments.

Kurt Vonnegut: Yes.

Marc Allan: They wanna post ’em at schools, and in public buildings, and things like that. What do you think about this?

Kurt Vonnegut: If you must, you can take a law to view those and have the Bill of Rights, which is strong, respectable body of regulations as traffic laws, as you can’t park by a fireplug, and you can’t keep people from assembling and complaining about this or that or whatever. All right, you’ve got me here because I only know the first commandment. I don’t know what the other set is. But, thou shalt have no other God before me. The Bill of Rights first amendment written by James Madison, I believe, will not allow that to be in school. Adultery, yeah, that’s disruptive to the society, surely. And murder, my god, and all the others. But anything that has specifically to do with the Jewish or the Christian religion just cannot be posted in the school. I like the rest of the commandments, thou shalt not kill, please, let’s put it every school.

Marc Allan: So the principles of the commandments are, the principles are great, but the idea of posting this and posting somebody’s religion for the school is what–

Kurt Vonnegut: The first commandment, and of course, it is very wise as whether Moses actually spoke to God or not, and whether God spoke to him. He was trying to maintain peace in a society, which was on the run then. And there were fights breaking out every night. This is a whirring wagon, trains moving west in this country, and he set these basic rules. Keep your hands off other people’s wives, don’t sass your parents, and all of these are fine. Let’s go with the 10 Commandments and throw out any which insist it would be either Christian or Jewish.

Marc Allan: You’ve talked in the past about public education and how much you appreciate independent–

Kurt Vonnegut: My free education, my god, you know, I had to buy notebook fillers.

Marc Allan: When you went to school, probably, it was quite a bit different than the schools that the kids go to now, but I think one of the things is, I bet when you went to school, no matter what, no matter how much money people had or didn’t have, that the parents sent the kids ready to learn, and ready to respect the teacher, and prepared to be quiet and listen, and take it in.

Kurt Vonnegut: Yeah.

Marc Allan: Am I right about that?

Kurt Vonnegut: Yes, but there, over 50% of marriages now go bust. So statistically, there aren’t such families anymore. And this isn’t because of sex madness or anything like that, it’s the nature of the economy and the nature of our entertainments and so forth. But yes, I remember, we had, I won’t say what his name was, but we had one doctor who was sort of our family doctor and everybody stopped speaking to him ’cause he got divorced. ‘Cause again, that’s a violation of the 10 Commandments, which are great rules for maintaining peace in any kind of society. But if God said that, you know, play the Ace.

Marc Allan: Do you believe in God, if you don’t mind my asking?

Kurt Vonnegut: No, hell, I don’t mind your asking, as I’m Honorary President of the American Humanist Association, having succeeded Isaac Asimov in that capacity. Yes, there’s a wonderful quotation by Nietzsche, it’s my hereditary religion, anyway. My parents, grandparents on both sides of the family were so-called freethinkers, and Nietzsche said, “Only a person of deep faith “can afford the luxury of skepticism.” And sure as hell, something enormously important is going on but I don’t wanna take Jerry Falwell’s word for it. For what it is, and actually, my ancestors who came over here, the first earliest ones came over before the Civil War, one ancestor on my mother’s side had lost a leg in the Civil War battle, they were Catholics. But they were also educated, never interested in science, and when Darwin came along, this was very convincing, and interesting to them. And so, literal acceptance of the Bible, Creationism and all that, was no longer possible for them, but they were sure as hell interested. Whatever it was that was going on, and also, so much family’s been in Indianapolis for a long time, frequently as merchants or architects, or whatever, and they had behaved with great honesty, I think always, very honest in their dealings, and did not lead crazy sex lives. So with that, what the humanist behaves well without any expectation of rewards or punishments in an afterlife, and they serve, as indeed my ancestors in Indianapolis had done, served the only abstraction of which was which of having any familiarity for just community, and that’s been enough.

Marc Allan: Well, I’d figured there was a word for what I am and now I know what it is, I’m a humanist.

Kurt Vonnegut: Yeah, but it was before the First World War, you would’ve called yourself a freethinker. But that was so specifically German.

Marc Allan: And I had been calling myself an atheist, but I’m not sure that that–

Kurt Vonnegut: No, or you could–

Marc Allan: Covers it.

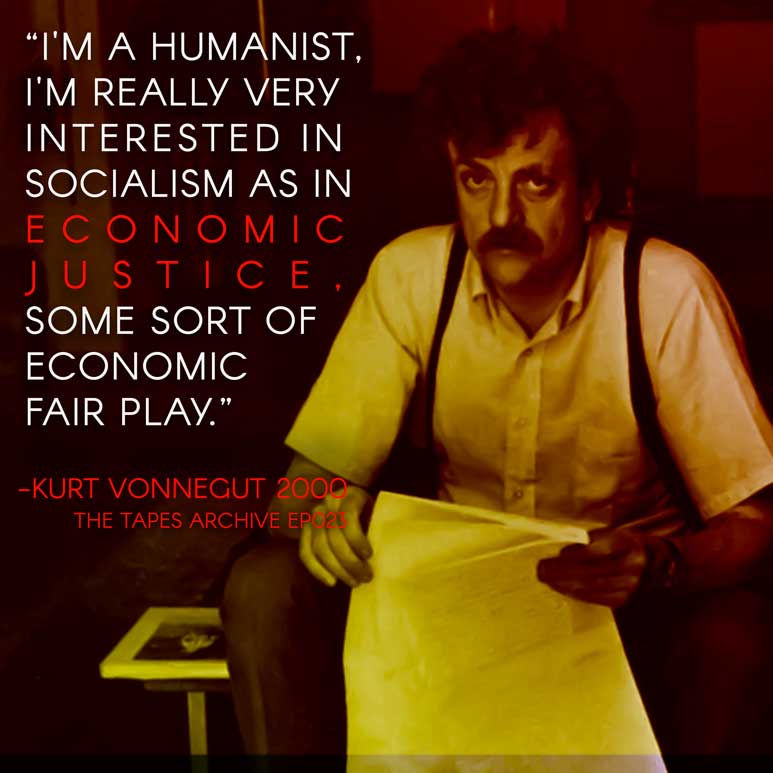

Kurt Vonnegut: Trying to trim your sail exactly and everything is, well, I’m an agnostic, ’cause I really don’t know enough. But anyway, it turns out, that some people are so scared by life, and should be, that they’ll take somebody else’s word for what’s going on and accept Jesus or whatever, and I’m all for that. And one interesting, not giving time, this is bad, what’s been said already ’cause I’m a humanist, I’m really very interested in socialism as in economic justice, some sort of economic fair play. When I worked with General Electric and burrowed away against socialism and Ronald Reagan was working for the company at the same time. Boy, was he ever against socialism. Of course, the company was against socialism because labor was a commodity, and if the working people decided they were entitled more than they were getting, this is gonna be a very expensive and messy. Karl Marx was invited to address a Marxist society in Washington, and he refused to do it because he wasn’t a Marxist. But what makes religion stick in any American cloth, and of course, this would be any civil libertarian too, is that religion is opiate of the masses. And in fact, what Marx was saying, and you know, he was a friend of the poor and the powerless, is that it was a comfort to them, and he realized this, and he was glad that such comfort existed. And he himself was grateful to opiates, probably, to opiates himself in treating pain when he had a toothache, or a headache, or whatever. And it was Lenin and Stalin, and people like that, Castro, I suppose, who used this as an excuse to silence preachers, because they have enormous power. Every Sunday, they’re just gonna get, stand up there and say almost anything.

Marc Allan: It almost relieved them.

Kurt Vonnegut: Yeah, but he was speaking well of religion, and not ill of it, and my particular hero is Voltaire, the speculator in slaves as a commodity, he had a lot of employees. And he had awful opinions of the Catholic Church, of the hierarchy, and particularly of the Jesuits. But he realized how important, how comforting this religion nonetheless was to his employees, so he never let ’em know how he felt about their faith, and limited his conversation to people of his own social and intellectual level. And I would do the same, and I would, what my particular war buddy who was a Roman Catholic, was Bernard V. O’Hare who became, finally, a district attorney after the war and then a criminal defense attorney. But anyway, he lost his faith during the war, it was such a mess that he gave up on Roman Catholicism, and I loved him and I hated to see him do that. I realized this was something very important and honorable if you could believe it.

Marc Allan: When I first came here, which was in 1988, there was a quote I always heard attributed to you about Indianapolis, was, “364 days the city sleeps, and one day it has erased.”

Kurt Vonnegut: Oh, I may have said that, but would be just regional humor. It certainly wasn’t, oh, no, I’ve spoken very well of this town.

Marc Allan: No, and that’s what I was gonna say, I just–

Kurt Vonnegut: And I did last night.

Marc Allan: It seems to me that you really have an affection for it.

Kurt Vonnegut: Well, why couldn’t I, why shouldn’t I be grateful with that wonderful public school system and public library system? During the ’30s, if you went to the library, the librarian was so glad you were there, is gonna help the little kid. Maybe you’d like this, maybe you’d like that, what are you interested in? I was crazy about snakes for a while. I thought maybe I was gonna be a herpetologist, and the librarian would say that’s a good idea.

Marc Allan: But I’d always get the impression that I think people thought that you didn’t care about, or didn’t like the city, and obviously, that’s untrue.

Kurt Vonnegut: Of course it’s untrue. No, but what I said, I was graduation speaker at Butler, I don’t know, three or four years ago, I guess, and I said it was all here. People so smart you can’t believe it, people so dumb you can’t believe it, people so nice you can’t believe it, people so mean you can’t believe it, and books, books, books, and lots of music. And what more could you want? It was during the ’30s. I was as unhappy as frequently as other teenagers are, and also The Great Depression was going on, some things at home would rather upset, and there was jazz, and it was black musicians.

Marc Allan: Could you go?

Kurt Vonnegut: Oh, yes, yeah, there’s a place called Southern Barbecue, it’s on Williams Street, which was where white people’d go to listen to black jazz.

Marc Allan: So who’d you see, what’d you see

Kurt Vonnegut: No, they would have been playing the blues and it would have been Piano, drums… Bass, saxophone and trumpet. And also, they had singing all the time too, all of them. And it was beautiful, and music is an enormous help to me right now ’cause I can comfort myself with music, with a CD right now. I’ve said I’m a humanist, but music is proof that there is a God.

Marc Allan: Years ago, I guess many years ago, you wrote a book called Canary in a Cat House.

Kurt Vonnegut: Yeah, the collection of short stories, yeah.

Marc Allan: And when I first started reading you when I was a kid, I went looking for that book, and I was always told it’s out of print, and the only explanation I ever got was that you wrote things in that book that you no longer believed, and you had asked to have it pulled.

Kurt Vonnegut: Not at all.

Marc Allan: Oh, okay, what’s the true, what is the situation? And do you mind if I close this blind?

Kurt Vonnegut: No, I just don’t wanna crap up our house with smoke. Now you asked me–

Marc Allan: Canary in a Cat House.

Kurt Vonnegut: Well, again, the religious rights didn’t want my stuff read. Not that they’ve read it that much, they’d just heard that it’s not all respectful of God. And the biggest trouble I ever got, I think, where people really raised hell was I wrote a story, I forget which one it was, where time travel, guys get time travel to work and everything, and so they decided to check out the bible story to find out it’s true about Jesus. So they go back, and yeah, it’s all true, and there are these three crosses, and Jesus is on the middle one, and he had said, it’s the Crucifixion story. But while they’re there, they decide to measure him, and he’s five foot six. Boy, did that

Marc Allan: Why does that bother them?

Kurt Vonnegut: Because he’s got to be 5’10’, he’s got to be–

Marc Allan: Oh, he’s got so he’s a little guy–

Kurt Vonnegut: Yeah!

Marc Allan: And he should be a big guy.

Kurt Vonnegut: Yeah! This was an insult, this was the most sacrilegious thing, and I could have said his eyes weren’t blue, too. I didn’t go that far. But that they would blow their stack, and of course, that must have been about the average size of a male back then, and Richard Lionheart was about that size, you can tell from his armor. But this would, I might as well have shit in the middle of the carpet.

Marc Allan: So that story was in Canary in a Cat House?

Kurt Vonnegut: I don’t remember, it may not have been in the collection, I don’t think it is.

Marc Allan: Okay, so then what did happen with Canary?

Kurt Vonnegut: Nothing, it did simply a commercial venture, and if the sales dropped below a certain level, they’ll pull it out.

Marc Allan: But it’s not even mentioned in future books, in lists what you’ve written.

Kurt Vonnegut: No, there’s no, no, that’s fine. I just forgot, I make that list, I guess I left it off.

Marc Allan: Okay.

Kurt Vonnegut: No, that’s not true.

Marc Allan: So you wrote this story and the religious right went crazy over it?

Kurt Vonnegut: In Battle Creek, Michigan. Dutched Reformed, I guess.

Marc Allan: And when you were in that position where people are firing at you and you’ve taken a very unpopular position, if something you believe in is something that’s unpopular, what do you feel like when you’re in the middle of that?

Kurt Vonnegut: Look, there are millions and millions of Americans just like me. It’s not a lonely situation at all, and it’s people with very specific agendas who go after a book, or a movie, or whatever. My situation is not remotely lonesome.

Marc Allan: This is kind of a big question and maybe you’ll think of a good way, specific way to answer it but, what did Indianapolis look like when you were a kid? One of the things I like to do when I’m out, I look around antique stores, and I found this antique store that had a lot of postcards. And I’m looking at the Indianapolis, they had Indianapolis stuff, and they have one of the Claypool Hotel. I’m looking at this and thinking, this is beautiful–

Kurt Vonnegut: Yes, it is.

Marc Allan: Why isn’t this here? And why did they erase this?

Kurt Vonnegut: And the courthouse, they took down the gorgeous, pillared courthouse.

Marc Allan: Yeah, why did they erase this? But tell me what it looked like?

Kurt Vonnegut: It was a utopia, architecturally, and my father and grandfather designed a hell of a lot of it and, we did our reunion, of Class of 1940 last night, I was asking people why did you leave town? Opportunity, theaters, beautiful homes to live in and all that, and best I could come up with is I think that The Great Depression so demoralized our parents, and so reduced their own self-respect. There was plenty of rainfall, plenty of topsoil, lots of minerals, and there’s no sewage company, and what did the city look like? It was boarded up, and I think that our parents were so upset and confused, and lost, not knowing what the hell to do with a failed capitalism, and I don’t know, but we left the town because our parents were so unhappy here. And then from 1929 to 1941, we got outta town. The people at our reunion, I mean, there was people who came from Tulsa, for God’s sake, and Santa Barbara, me from Northampton, Massachusetts.

Marc Allan: Is that where you’re living in?

Kurt Vonnegut: Uh-huh.

Marc Allan: I really like this book, because I learned more about you. I guess I was trying to think of when I was a kid and I read all your books, and I guess I was interested in the fantasy, and the mind of the things you would create, and now I’m more interested in the mind of the man who created them. They’re just two passages here, and if you wanna react to them, that’d be great. I just think, where you were talking about writing and you said, “I feel and think as much as you do, “care about as many of the things as you care about. “Although most people don’t care about them, “you are not alone.” And I thought that was just such a, you talk about the experience of writing as such a great comfort.

Kurt Vonnegut: Yeah, well I lucked out because there were those people out there, and I know, had close personal friends, perfectly wonderful writers, who did not have the success I did, but all of us write what we must write, and then it becomes real life. I mean, there is somebody like Stephen King, a friend, I like him, I respect what he does, who can craft these stuff for market, but… Almost all of us are helpless not to write what we do write. There’s a mentality there, and then you just have to see what the hell happens, and explain to your wife what went wrong.

Marc Allan: The other passage was when you said that you were writing back to the woman who was pregnant, and was a mistake to bring the baby, and you were talking about the saints that you met. I think it’s interesting because you seem to have a great belief in people.

Kurt Vonnegut: Well, I’ve been lucky as hell with it. And interestingly, Philip Roth’s new book is about betrayals. He, himself, apparently feels betrayed against, and he kinda needs a friend in the helplessness not to write what he wrote. But it’s what The Human Stain is, very dark book, it’s about betrayals and all that. I’ve seen betrayals on a large scale, but not on a personal scale. I’ve seen this country betrayed, seen Germany betrayed, twice, and my own division was betrayed, they were using us to bait and trap, I’m sure.

Marc Allan: Can you tell me more about that?

Kurt Vonnegut: Well, when I went to work at General Electric, my boss there, this was public relations, publicity, was a colonel, had been a colonel. He kept saying to me, why weren’t you in offices? Personality flaw, well, I’d been a bigshot at Cornell University, and officer in my fraternity, and became magazine editor of the Cornell Daily Sun, which was just the regular morning paper, and all that. But I always just kept to PFC, and not through any personal fault, ’cause they had enough officers, they had enough non-coms, and they stockpiled a whole bunch of us college kids. So they sent me to Carnegie Melon, Carnegie Tech was what it was then. So I studied mechanical engineering there while being stockpiled and getting to PFC, and then to University of Tennessee to flunk thermodynamics again, and then they needed the grunts. Got to carry a rifle, they aint started to need any lieutenants, they just needed a human wave. And so, we were all sent to infantry divisions and I wound up in this crazy division, 106, which was based in Camp Atterbury, and the 106 had been stripped of all of its enlisted men, but the non-coms and officers were still there. So there was no chance of promotion. So it was a division of college kids, and then we were, D-Day was in June, and in October we were sent overseas, first to England and then to France, and by then, our armies were right on the borders of Germany in December. And so we replaced it, took D-Day out of the second division. We were college kids, demoralized with no chance of promotion, and actually, I was an infantryman, a scout, a battalion scout without infantry training, I’d had no artillery training. So we took over their positions in a perfectly quiet front, and then the Germans staged their last big attack right through us. And Jesus, I mean, we didn’t have any tanks. It was an overcast, so we didn’t have any planes either, and the Germans just knocked the shit out of us. Came right through and destroyed the division to pieces, and the order came down from a regimental commander, he’d surrendered, they’d captured him. And so he ordered us to surrender, which is a pretty illegal order, it’s like saying, commit suicide. So hell, there were fragments of the division, wandering off through the countryside in the snow, and this was intentional because the Germans headed for Antwerp, it was bizarre. But all of the tanks they had left, which were pretty tanks, believe me. When I was wandering around, they hadn’t rounded us up yet, and we were being hunted like animals, where the hell an American might still be. But that front was, I don’t know, when I was captured, the front was probably 30, 40 miles away, leaving no But the German penetration was very long and now, not a good idea. And so, the last of the tanks were captured, and the last of the troops were killed or captured, and that was intentional.

Marc Allan: On our part?

Kurt Vonnegut: Yes, to have them come right through us and wail or attack far, farther than that. But their flags were completely unprotected

Marc Allan: So what happened to you?

Kurt Vonnegut: I was captured.

Marc Allan: And?

Kurt Vonnegut: With 102 others were killed or whatever. But we were, I mean, hell, we knew as soon as we got there, we were fighting for our lives, and we thought maybe that’s what everybody’s been putting up with on the front and not at all. But I think that was, they could never say so. It’s like a gambit in chess. You tempt a guy with a pawn and he’s lost the game.

Marc Allan: So you were captured, did you end up as a prisoner of war?

Kurt Vonnegut: Yeah.

Marc Allan: For how long?

Kurt Vonnegut: Well, from December till, actually, the war ended May 8, approximately May 8, political when the war actually ended in Europe. Soviet Union said one thing, we said another, but it was around May 8. But then I was in the Russian zone, what became the Russian zone, I saw them come in. And they locked us up, and then they put us just in a regular jail, regular block, and then they traded us one for one across the Alps for their own people who were in the hands of the Americans. But there wasn’t anything to eat, so it was onerous on that account. But my god, like the time some guys during the Vietnam War were prisoners was unbelievable, years. I did five months. Again, we were in hard labor ’cause under the Geneva Convention and the treatment of prisoners of war, privates must work for their keep, and non-coms don’t have 10 offices. But actually, it was so much more interesting to be working in a city than to be out in a countryside. Just behind barbed wire with just people to talk to.

Marc Allan: So what did you do? What kind of labor did they have you doing?

Kurt Vonnegut: Well, it was factory work, and it was packing and shipping food, and canned fruit and sweeping floors, repairing busted windows and stuff like that. We had to walk to work everyday and the factory was quite a distance. But then after the city was bombed, it was burnt to the ground. The Brits did that, we didn’t do it. We were digging out corpses out of cellars. There were no air raid shelters in Dresden, there’s certainly not many. And so people just simply went down into ordinary cellars, like what’s under this house. And about 135,000 people died, essentially, of suffocation.

Marc Allan: Collapsed and–

Kurt Vonnegut: No, now the city became one column of flames so there was nothing to breathe. But the Brits did it, we didn’t.

Marc Allan: So now I have a better idea of where Slaughterhouse-Five comes from.

Kurt Vonnegut: Yeah, yeah, no, it really was an experience. But I wasn’t Billy Pilgrim. Was a good soldier. They probably said last night, the only copy, but this… It answers some questions, really, is roughly what I said. I was describing out here what exactly I said, Couple months ago.

Marc Allan: You mentioned in here that you didn’t come back for your 50th reunion.

Kurt Vonnegut: No, I had Lyme disease.

Marc Allan: Oh, okay, but you pretty typically do come back for your–

Kurt Vonnegut: No, this would be the only reunion I’ve ever attended.

Marc Allan: Why’d you decide to come back for this one?

Kurt Vonnegut: It was time.

Marc Allan: You were talking about betrayal and I interrupted you. If you could go back and finish that thought about you’ve never, you were saying that you hadn’t experienced betrayal.

Kurt Vonnegut: I’ve had institutional betrayals, but of my division friends in serving my country. But it was cockamamie, the things with Congress were different to the House of Representatives. But no, I personally have, I’ve never been seriously double crossed. You’d have to ask him ’cause he doesn’t say so overtly, but it’s implied… About how treacherous people are, or can be. I don’t think so.

Marc Allan: So, it’s been a good evening, this has been great. I mean, it’s been a good life.

Kurt Vonnegut: Oh, I think so, what I said about the Second World War is that it was a great adventure, I wouldn’t have missed any of it. But I saw a whole lotta shit, and heard a lot. When I was finally captured, we were marching into Germany, and victorious troops were going the other way riding on top of the tanks and high as kites and everything. That was interesting.

Marc Allan: Did you see the movie, Saving Private Ryan?

Kurt Vonnegut: No. I had a friend named Howard Zinn, who was a bombardier during the Second World War, and, he doesn’t like any movies like that, and neither do I because it makes war reputable.

Marc Allan: But the war you fought–

Kurt Vonnegut: It was a just war.

Marc Allan: Was reputable, yeah.

Kurt Vonnegut: The war itself isn’t. I’ve said that the, there was great resistance to Catch-22, and then finally became the most popular of all American postwar, World War II novels. Heller was a good friend of mine. But it teaches a lesson most people don’t like to hear. As a military person, in even the most just of wars, which the Second World War was, find themselves behaving in manners which are disgusting and insane.

Marc Allan: You’re saying here that Crown Hill won’t get you. Do you have plans?

Kurt Vonnegut: I don’t care, no. And I wouldn’t want, I’m a currently humanist, I have no fear of death and don’t care. Walt Whitman, is some Englishman realized what a great poet he was. So he was really more respected over there than here ’cause they’re really into poetry over there, which Americans So a group of young Englishmen passed the hat for him over there, came over and found him, and I think he was living in some sort of cold water flat in Camden, I forget where. So they gave him this money, and he blew most of it on a mausoleum. Oh, but Henry, I’ve seen Thoreau’s tombstone. It’s about six inches, maybe, on its side, little plug in the ground about this high, that’s Henry.

Marc Allan: Will you be buried?

Kurt Vonnegut: No, well, I’ll be cremated.

Marc Allan: Cremated, yeah.

Kurt Vonnegut: Yeah, but I had a friend, one of my POW friends, really wonderful man, Tom Jones, buried in Arlington. And so I saw that one, you know how many people are buried in Arlington everyday? Seven.

Marc Allan: Oh, is that right?

Kurt Vonnegut: I don’t mock it at all. I think it’s an honor to be buried there, and I don’t think there’s anything cynical about the operation there. There’s a beautiful big building for families to gather and that waits for you from the jumps that way, or whatever. But then you go out there and there’s a chapel, representing your particular faith if you had one, and guys wearing, if you’re in the army, they’re wearing dress blues, which I hardly ever see, they’re beautiful. They got the stripes down the pants and all that, and they got rifles, fire ’em off, another guy blows Taps, it’s good. For Tom Jones, PFC, 423rd Infantry, deserved it and but what they do is they want you to be cremated, arrived cremated, and they essentially bury you with a post hole digger, and I guess they put a cam down there, but the marker is quite handsome and dignified. Yeah, I’d kinda like to be Arlington for the sake of that, being upstate, 423rd Infantry.

Marc Allan: And then growing up, you had the disadvantages of The Depression and all, but I think more focus on what’s important in life, and I wonder, you look at kids growing up today, and there’s so many distractions. There’s so many things that take people’s eye off the ball.

Kurt Vonnegut: The biggest industry in this country is drugs. I mean, there are salespeople everywhere, even an prep schools. And the greatest university, get them in the performance industry. And again, we have progress, this is chemistry. No, but the talk about money, a linebacker gets three million dollars, and your dad is a honest workman of some kind. Yeah, money madness and there are all these drugs, and they are so available. What to do about that is take the profit out of it, which is what they did with alcohol. I mean, that’s not a good idea either. But, what can they believe in? Well, you can believe in the Bill of Rights, you can believe in the Declaration of Independence, and what the ACLU here did do, the chapter, is to be the first one, is to come out full board for the Second Amendment, and to get everybody into a well-disciplined–

Marc Allan: That’s right, and give them all muskets, or something like that.

Kurt Vonnegut: Yeah, but they got a drill. They got a drill, they’ve got to, starting to take orders. What’ve you got? And I want one, just grab the Second Amendment.

Marc Allan: Have you ever, aside from being in the army, have you owned a gun?

Kurt Vonnegut: Oh, of course.

Marc Allan: Really?

Kurt Vonnegut: My father was a gun collector and sure, he used to go out to, you used to be able to go out to Fort Benjamin Harrison if you were a kid, and your dad was with you, and they’d give you this green field and ammunition, and you’d fire on the range out there. So we’d be really ready when the next war came along. But the whole class of 1940, at short reach, and all previous classes, were pacifists. We were not gonna get suckered into another war, and yeah, First World War was about absolutely nothing. People were gassed and drowning face-down in water-filled shallow holes, and draped over the barbed wire, and it was about absolutely nothing. No, we’re never gonna do that again. But then a just war came along, which was, in a way, a national tragedy because ever since we’ve thought of ourselves as the good guys, which we were.

Marc Allan: Are you really never gonna write again?

Kurt Vonnegut: I don’t know, ’cause I wrote this and… No, I didn’t expect to live this long. What’s interesting is that a writer’s best years, Hemingway, Steinbeck, during their 20’s and early 30’s, they wrote better than they had any right to. They were just winging it, and then it stops. The chess masters are through about 28 to 30, and I think Bobby Fischers seek it, really, in what our belief, this country’s produced two chess geniuses that I know of, Paul Morphy’s the other one, and Morphy was through about 28, 29, and 30.