Ian Anderson from Jethro Tull 1993

I was a devoted Jethro Tull fan growing up, so I relished every chance I had to speak to founder and leader Ian Anderson.

In this conversation, which took place during the 1993 tour celebrating the band’s 25th anniversary, Anderson, then 46 years old, talked about Tull’s legacy (“almost an important band”), the best Tull albums (Stand Up, Songs From The Wood and Crest of a Knave, because they contain “the right balance of serious, humorous, complex and simple stuff”) and an event that brought together 16 of the first 22 members of Tull (there have been many more members since).

Anderson is consistently erudite and witty—very much a reflection of the music he’s made over the past fifty-plus years. And sometimes, as you’ll see when he gets to talking about Metallica and Guns ’N Roses, he also can be very wrong.

One note: In this interview, he refers to an upcoming Jethro Tull album that the band recorded in 1972 but never released because the recording sessions “foundered in technical disarray.” That record was “Nightcap,” and it is, indeed, a mess.

For more information about Jethro Tull, visit jethrotull.com.

And if you want to listen to the best of Tull, I recommend: “For A Thousand Mothers,” “To Cry You a Song,” “My God,” “Dharma for One” and “Cold Wind to Valhalla.” Anderson also has released several solo albums, the best of which are “Divinities: Twelve Dances With God” and “The Secret Language of Birds.”

Ian Anderson Interview Transcription:

Ian Anderson: Hello, Marc Allan please.

Ian Anderson: Hello, Marc Allan please.

Marc Allan: This is Marc.

Ian Anderson: Hi Marc, this is Ian Anderson from Jethro Tull.

Marc Allan: Hi Ian, how are you?

Ian Anderson: I’m very well, I’ve just been speaking repeatedly to a young lady, I mean quite a young lady from apparently on a phone number that’s 663-9398, that I’ve been calling for the last 10 minutes.

Marc Allan: Oh wow.

Ian Anderson: And finally had to explain what I was trying to do and that her mom looked up your telephone number and I’d got the, well, whoever gave me the phone number had got it wrong. So somewhere out there in a suburb not too far from you is a young lady who is very bemused by the fact that some strange English person from a rock band called Jethro Tull, which she’d obviously never heard, trying to reach her to talk to her about our forthcoming tour.

Marc Allan: Gee, would’ve been kind of exciting if you had reached a fan, you know, and then somebody was really thrilled and kept you on the phone.

Ian Anderson: Actually, I think the girl had heard of us, but when she said to her mom, she said, “What’s that, a delivery service?” ‘Cause I thought it was gonna be like she was gonna get through to her mom, I said mom, Mom said, “What, let me speak to him.” But no, Mom hadn’t heard of us but little girly had, maybe little girly wasn’t so little but she was, you know, we’re talking teenage. But then a lot of our fans are these days, and who’s complaining.

Marc Allan: Really, you’re finding you’re getting a young audience?

Ian Anderson: Well, I mean, yes, in the same ways a lot of young people go to museums and art galleries, the sort of things-that were way back, sure.

Marc Allan: Don’t say that. I was thinking it was 20 years ago this month that I saw Jethro Tull for the first time, saw on the Passion Play Tour so, yeah it’s a long time, 25 years now overall, as you look back on it you’ve had some incredible highs, a few things maybe that are being considered lows, is there anything you’d change?

Ian Anderson: Well, I’m sure there are lots and lots and lots of little things that I would change, I don’t think I’d change any of the big things but, you know, lots of little things, sure. I mean, like trying to remember to play an F natural as opposed to an F sharp in some particular songs somewhere but yeah, I mean I suppose it’s not been a disastrous series of events, it’s been interesting. But, you know, we are amongst those few people who are still around from the earlier days of rock music, as it took off in the big sort of era of the late ’60s, early ’70s into the arenas and the stadiums of the USA. I mean, we’re one of those surviving bands who still has an audience of a few thousand people, and, you know, we’re not the biggest band in town, but we have a meaningful following. Considering the nature of our predominantly uncommercial music, I suppose we’re lucky to have anybody coming to see us at all, because we don’t do the straightforward stuff, we kind of fool around a little bit. On reflection, we’re very lucky to have an audience given that we are that sort of a band that did the stuff that other bands didn’t do rather than follow the mainstream of rock.

Marc Allan: You had mentioned having this audience coming out to see you and it seems to me that groups from the ’60s, ’70s and so on seem to have the biggest followings today. Concert tours by groups that have been long established are doing very well, whereas newer groups are having a harder time attracting concert audience. I’m wondering if you think that’s any kind of comment on the state of music now?

Ian Anderson: I think it’s more of a comment on the state of the economy really, because people are concerned about value for money and if you feel that you’re gonna get value for money by going to see a band that is, or an artist, that’s been around for many many years, that seems to have deliver the goods and promised some kind of a payoff in, perhaps not spectacular but acceptable, terms then, you know, value for money seems to be an important part of persuading people to part with their ticket price. I also have a sneaking suspicion that maybe the glory days of the big production kind of shows might be coming to an end, I think that if you’re at the forefront of that large-scale touring event, you know, the U2 tour, or the Guns N’ Roses, or the Metallica, then you can do very well, but a lot of the time it doesn’t do too well, or it doesn’t do too well two years in succession. I know that the bands like Guns N’ Roses, Metallica, have probably not enjoy the same success second time around in some of their appearances in the last few months than they did a year or so ago. It’s somehow satisfying to be around in a kind of echelon that depends upon enough 2000, 3000, 4000 willing punters coming to see something that is a musical performance rather than the state of the art, or the state of the month, in the sense of being current, the popular thing to see, the popular thing to do.

Marc Allan: But, I think about it now and I’ve seen you about 10 times maybe a little more over the years, and I can’t remember a crowd of less than 10,000 people and I’ve never seen you in a place other than an arena.

Ian Anderson: Really?

Marc Allan: Yeah

Ian Anderson: Well, because we’ve been playing theaters since we’ve started, and it’s also been a very important part of Jethro Tull concert going activities to try and make sure that we play in a variety of scales of events, and indeed the 2000 seater theaters are sort of something I very much have tried to keep a hold on over the years and in the sense of keeping that as a viable thing. I mean, sure we play the arenas and the festivals and all the rest of it but, you know, we also try and fit in theater tours as well. Where have you been seeing us play?

Marc Allan: Madison Square Garden.

Ian Anderson: Okay. Well we don’t, you know, I mean–

Marc Allan: And Boston Garden.

Ian Anderson: We’ve got a couple of shows in New York next month,

Marc Allan: Right.

Ian Anderson: Or later this month, whenever it might be. Kind of, I don’t know, 10, 20,000 places that may or may not be full, I think they probably will be full, but we’re also playing the places where we’ll probably only play to, you know, 3 or 4,000 people and some of our concerts you know, we play for, I mean this last European tour, we played for maybe 30, 40,000 people one night and maybe 2,000 people the next night in some village square in the middle of the Austrian out. That for me is really exciting, you know you don’t get sucked into this kind of one level of performance where you’re dealing only with big crowds and big, sort of, big events, big gestures. I think it’s very important to try and keep this contact with smaller groups of people as well. I mean, I much prefer playing to, I mean, it’s much easier as a performer to deal with people when it’s kind of a couple of fans and folks, then you really feel you’re kind of reaching to all of them. But it’s very hard, when it gets more than about 5,000 people, you know, some people are getting short-changed, no doubt about it. I know that, because I’ve been in the audience and I would rather go and see an act play, you know, in a smaller venue anytime, anywhere.

Marc Allan: Well, maybe that’s the drawback of growing up on the East Coast where you were enormously popular. Until maybe fix, six years ago I think I remember seeing that you’re playing in a theater in St. Louis and that was probably the first time that I ever knew of Jethro Tull playing a theater in the United States.

Ian Anderson: Hm, well I was actually looking through some dates the other day, and I was astonished to see we were playing theaters fairly consistently, not every day, but I mean here and there, all the way through our career in the USA. There were quite a few theater dates and I know because, having seen them written down, I remember them, and I can remember those more readily than I remember, you know, the kind of arena or stadium type dates which sort of blur a little bit. Whereas those theater dates tend to have something about them that causes you to remember the actual time and place and who was on and what you did.

Marc Allan: Let me go back and talk about some of the material over the years you, especially early on, sung a lot about God and religion. When you look back on that material now, how do you feel about it? Have you changed your mind?

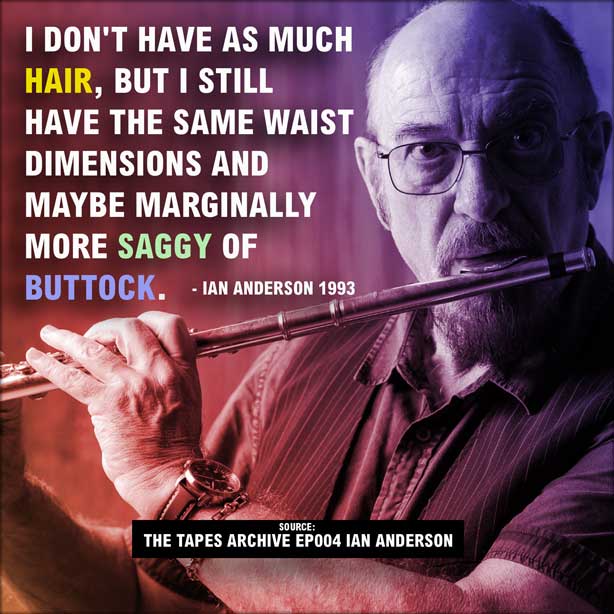

Ian Anderson: Yes, but only a little bit. And most of it I’ve changed back again to how I felt then. I think that one of the reassuring things about growing older is that a lot of those childhood philosophies and views that you form in the midst of puberty and the conflicting emotions of the hormonal disturbance are not flashes in the pan, one off things, I think they’re actually very formant and very important emotions, some of which probably stay with you for life. And a lot of those things that I was thinking and singing about a few years later, I’m still fairly comfortable with in terms of opinion and thought, now looking back on them. There may have been times where I might have changed my views or at least entertained alternatives during my life but I think, pretty much, I go along with the Ian Anderson of, you know, 1970, ’71, ’72. I mean, I’m sort of not such a different guy, I don’t have as much hair, but I still have the same waist dimensions and maybe marginally more saggy of buttock. But basically I’m pretty much the same guy.

Marc Allan: No more codpieces.

Ian Anderson: I mean that is very reassuring, when those things come back to you, you know you think well, wait a minute that’s kind of what I used to think. It’s surprising, in a way, that you don’t change more than you do. But I’m sure it’s not just me, I’m sure it’s everybody, or at least a lot of people who find that those really formative years are very crucial in the sense that they put those sort of strong building blocks of your opinion, of your sort, you know, the way you weigh things up. They provide a foundation for your later life. You may change a little bit, but it still builds on that foundation of the exciting and dangerous years of puberty.

Marc Allan: I think that if you talk to some of your contemporaries that they would probably cringe about some of the things that they wrote when they were young though, so it’s kind of reassuring to know that you stand by what you wrote then.

Ian Anderson: Well, I certainly cringe about some of them, but only some of them.

Marc Allan: Can you give me an example?

Ian Anderson: Well, there are things that I, I mean, if you want to take that period of time, say 1970, if you take the Aqualung album, there are songs like Aqualung which I think are thoroughly relevant and good songs in a sense they’re about very real, contemporary, and social realities. They were songs about then, they’re songs about now, they’re songs about 20 years from now, there will always be people living in cardboard boxes and about whom we have ambivalent feelings and find it difficult to relate. But there are other songs on that same album that I think are a little heavy handed and a bit awkward. I guess I would say that probably 50, 60, 70% of the things I’ve written I’m not too embarrassed about. And probably about 25% of them I’m quite proud of having written. But I mean out of 250 songs, we’re probably talking 50, 60 songs that I’m really very, very pleased with. You know 50 or 60 songs, you know we’re talking about 10 symphonies. I mean Beethoven only managed nine and a half, so I think I’m in with a chance,

Marc Allan: Okay.

Ian Anderson: by my own evaluation. Not that I’m saying what I do is as important, but just in terms of self satisfaction I think there’s quite a body of material in the stuff that I’ve done that I’m not only not embarrassed about, I’m actually quite proud of. And then there’s that bunch of stuff that I wish I’d never seen before but, you know, you have to accept that you did it.

Marc Allan: How does My God stand up?

Ian Anderson: Oh, that’s okay, that’s okay. Yeah, I mean, that’s not a difficult one to deal with, no, that’s okay.

Marc Allan: And what about Thick as a Brick and A Passion Play?

Ian Anderson: Well, Thick as a Brick is a sort of an amusing thing because it was a response to the critics who saw Aqualung as being some kind of concept album. So we tongue in cheek and with good humor, delivered duly a concept album which was deliberately overblown with kind of a crazy way over the top almost Monty Python-esque parody of what a concept album is supposed to be. But it was done with a sense of humor and warmth that I don’t think alienated the critics or the public. It kind of hit the spot. The difficulty was in following that up, we then went to do an album which sounded in technical disarray, because we were working in a studio in France where things just went horribly wrong and we kind of struggled for some months to get something completed which didn’t really work out. Although, strangely it will in fact be released in December this year as a part of a two CD set, the missing 1972 Jethro Tull album will, in fact, nearly all of it, be heard probably by you and a few others. And it’s kinda good fun, again it has a sort of warmth and humor about it, it’s not the best music in the world, but it’s sort of amusing as a piece of early ’70s stuff. It’s a historical document. Passion Play was the follow after that when we went back to England and had to kinda start again and largely new material and a new approach. Imagine if you spent three months of your life working on an album and it had all gone horribly wrong and you had to then pick up the pieces and kind of get a record delivered. Then it was, I don’t know, some of the humor went out of it. And that for me is the only problem with Passion Play, is that it is a rather a humorless, it’s just a little bit too serious and deadpan. It therefore sounds pompous and totally grandiose where it wasn’t supposed to be that way, it was supposed to be more, or a bit more, kind of tongue in cheek, but I’m afraid the levity got lost in the foundering attempts from the Chateau D’Herouville in Paris in 1972, so that’s my excuse.

Marc Allan: Well,

Ian Anderson: What King Crimsons or Emerson Lake and Palmers, or Yeses or Deep Purples, what have they got to say for themselves?

Marc Allan: I don’t know though don’t trash Passion Play too completely, because really, it’s one of my favorite all time albums.

Ian Anderson: I’m not trashing it, it’s just a little bit short on the kind of warmth, it just missed that thing, you know, it just didn’t quite convey something which was supposed to be a little bit of fun, it was too deadpan, you know, there’s a kind of tiredness about the recording process at that moment, it just somehow didn’t convey the thing that was supposed to be there which was a little bit of tongue in cheek and warmth and fun, which was certainly there with Thick as a Brick and indeed was there with the album that didn’t get completed. But hey, Passion Play is not, I don’t look back on it and think, oh god, what a terrible record, I just think it was a record that was lacking an ingredient that could so easily have been there if we hadn’t been a little bit jaded through the dislocation geographically of taking to another country to make a record being tax exiles and you know, having the problems with girlfriends and family and wives being in a strange place. It weighed heavily upon us, and, you know, in a soulful sense we got a little bit too pedantic about it. But hell, that was 1973.

Marc Allan: Yeah.

Ian Anderson: A lot worse things happened, I can’t remember what but I’m sure they did.

Marc Allan: Well, if it makes you feel any better, I think that album stands up remarkably well. I was listening to it today, and I listen to it pretty frequently because it’s one of my favorite records and, I don’t know, I think there’s enough spots of humor in there and certainly enough that people can read into it or not read into it as they see fit. And I think it’s–

Ian Anderson: Good, well, it’s okay.

Marc Allan: Yeah.

Ian Anderson: It’s kind of a seven and a half out of ten one, because there have been worse but there’s been many better.

Marc Allan: Okay, your more recent albums, A Catfish Rising, Rock Island, how are those going to sound in 20 years do you think?

Ian Anderson: A seven and a half out of ten.

Marc Allan: Yeah.

Ian Anderson: They’re kind of, you know, they have their moments too. I think that, I mean, the one before that,

Marc Allan: Crest of a Knave.

Ian Anderson: Crest of a Knave. Crest of a Knave was a good kind of balance. Crest of a Knave is a sort of 1980s version of standup. It has a good, eclectic mix. That has a good balance of material on it, and so, strange thing, you only see this kind of after the fact obviously, otherwise you wouldn’t complete them the way you do, but Crest of a Knave had a good balance to it. And some good songs, for me it’s kind of like standup. A middle period Jethro Tull album like Songs from the Wood, again, are put in the same vein of having a sort of right balance of kind of serious stuff, humorous stuff, you know, complex, simple, they’re kind of balanced records that seem like the product of a sane and comfortable individual with at least two or three major credit cards to his name. So, I mean I would always recommend those. But if I had to stop and recommend any particular album to anybody, the tedious but truthful response would be that I would go for one of the best of albums, probably particularly the one that’s out at the moment, the two CD set and digital remasters, which are, truly, genuinely original mixes. But they do, I think in every case, sound better than they would do on their original albums as they sound today. But the digitally remastered best of of whatever it is,

Marc Allan: I have those, yeah.

Ian Anderson: 30 odd songs, whatever they are. I mean that’s the kind of thing that I would say well, if you were a first time Jethro Tull buyer then probably a good thing to go for. Similarly, if you were someone who bought a lot of Jethro Tull albums on vinyl in the past and wanted to buy, you know, replicate them all in CDs then I would say that something like that is a good cross section of the things that, you know, it is just that, a cross section. It’s not including everything, but it’s a bit of this a bit of that, and it gives you an overall picture. So, particularly for the younger fans, you know, people maybe coming along seeing Jethro Tull for the first time, or buying their first, second or third Jethro Tull album, then those best of things are a pretty good deal if you’re looking for an answer to the whole picture, I mean, I speak as one whose recent purchases include sort of Stranglers’ best of and box set and things from those, the Ramones. ‘Cause I go for that, you know, I’m not gonna go and buy all their bloody records ’cause the chances are that eight out of 10 songs are a pile of shit. You know, I’m gonna go for the box set on the grounds that they are the proven track record things over a career of some, you know, well whatever it might be, 10 years or 20 years or five years depending on your status. But, you know, the compilation is not a dirty word, I think it’s a pretty good way of getting an overall picture fairly quickly and then if you like what you hear you might then start investigating it and going back into the minutiae of detail surrounding some particular album. But, you know, I kinda like those compilations, box sets. I buy ’em all the time. I mean I’ve finished staring at a Muddy Waters compilation actually on my study desk as I sit. You know, I’m a compilation kind of guy. Ain’t nothing wrong with those. And they’re usually cheaper.

Marc Allan: Yeah, well, in the overall scheme of things it’s certainly cheaper than buying every Stranglers record, or something like that. I guess if you’re gonna divide Jethro Tull records into periods, as you seem to have done, it seemed to me that after Songs from the Wood, you had, and I’m probably wrong about this, but it seemed like you had a harder time coming up with ideas of things that you wanted to write about that were really personal and affected you. And I’m wondering if I’m just reading something into it, or if there is any truth to that.

Ian Anderson: No, I don’t have any problem writing things that reflect my feelings and emotions and interests at all, but I, you know, obviously have more of a problem when I have to accommodate the kind of musical aspirations and interests of other members of the group, so you know the problem for Jethro Tull has always been that there have been, first of all, a lot of different members in the band, each of whom have come with their own idiosyncratic expressions regarding sort of the way they play music, their preferences for different kinds of music, their personalities as they affect the music, and, you know, first of all you write for yourself, and second and fairly closely as a second, you tend to think about the people you’re working with, and you hope to impress them, and make them feel good about what you’re offering up to them to play. So, I mean, is there a difficulty that tends to be…

Marc Allan: Well, you were in the middle of a sentence and then you weren’t there anymore.

Ian Anderson: Yeah, well, that’s right. I got to the end of the sentence and you weren’t there anymore.

Marc Allan: Anyway, so can you continue that thought, you were saying you were writing to impress other members of the band?

Ian Anderson: Sure, I mean that’s a big part of it, that you’re aware of other people’s preferences and their wishes to express a certain thing and you find yourself either consciously or subconsciously working with that in mind and it’s the way that it is, you know, I don’t think anyone is a true solo performer. I think you’re always however out on a limb you might seem to be, you’re always kinda working with somebody, even if it’s just the recording engineer or the tape operator, there’s more than one viewpoint at work.

Marc Allan: Did becoming successful in terms of audiences and making money and all that change your perspective about what you wrote and sang about, you know, does it become difficult to write about the church or religion or whatever when you’ve been so fortunate to be as successful as you’ve been?

Ian Anderson: I don’t think it’s difficult to write about the church or religion, but certainly there are some subject areas that do become more problematic, because you’re dealing with simple ideals and sort of universal kind of street sort of values. Then it is difficult if you got a few million in the bank it must be difficult if you’re in U2, for example, to be a preaching kind of a band, when, you know, the most of people you’re preaching to are you know, compared to yourself, extremely poor. It must be difficult if you’re talking about certain values and you’re Michael Jackson and you own half the known universe. Of course it’s difficult but at the end of it all we have our pride but areas of conflict with our own world with all verses that sort of universal guilt that we must all feel that there are people who are much less fortunate than us, and maybe we address it and maybe we don’t. I mean, I do but the way in which I do is probably quite different to the way in which Michael Jackson does. We’re talking different also in quantitative terms as well. So I think the answer is obviously a dilemma at work there as soon as you become monetarily successful as a musician, you immediately tread on very, very thin ice when it comes to the some of the subject material and some of the sentiments that you might have expressed when you were a poor, penniless, struggling musician. That’s one of the things you have to cope with. And at that point it’s best to get rid of the limos and the dark glasses, it’s best to shed the trappings of show biz, and you know, kind of just be one of the guys as much as you can. I mean, it’s easier to deal with Phil Collins making a lot of money, than it is to deal with Michael Jackson or Madonna making a lot of money because Phil Collins doesn’t seem too show biz, that he’s gonna upset you. Whereas Madonna is sort of archetypal Hollywood show biz power crazy, sort of over the top. I mean I don’t think anybody really likes Madonna, that’s the sad thing, and yet there’s a lot of talent and, you know, character there. It’s just that, you can’t like this woman, you know, it’s so sad, isn’t it?

Marc Allan: Yeah.

Ian Anderson: I’m sure some people like dear old Phil.

Marc Allan: Eh, throw Phil in there with ’em. Give the money to somebody else, let’s not give it to Phil either. Let me see what else I wanted to ask you about, it said in one of the bios, and some of the bio material that have been sent that there was a reunion not long ago of former and current Tull members, is this correct?

Ian Anderson: That’s right.

Marc Allan: Well, what was that like, when was it?

Ian Anderson: It was pretty weird at the beginning, because it wasn’t our idea, I mean any current or ex Jethro Tull member’s idea, it was the idea of the director of a video that EMI wanted to make of sort of 25 years of Jethro Tull. He wanted to get everybody together and we all kind of cringed a bit. And so in the end, then I thought, well you know, we’re either going to end up with a halfhearted response that will be really embarrassing or we’d better try and get really everybody there in which case I have to get on the phone and call people. So I did, and there was a lot of resistance among some members but as soon as they felt that there was a sort of genuine will to see each other again, you know, it kind of snowballed into, I mean really every single person would have been there, except that two or three of them were on tour. One, his new wife was having a baby that day, you know, 5000 miles away and you know, one was dead. And I mean apart from that, everybody turned up so it was I think 16 out of 22 people, and it was surprising because all these people, some of whom had never met each other before which is really interesting thing, I mean they were kind of, “Oh, you were the guy who was there in ’74.” And it was quite extraordinary. But there were a few people you expected to have tense moments exhibited, but they weren’t, but some of the people you thought were kinda gonna be really awkward in each other’s company were actually okay and then, strangely, there was a little tension between people you didn’t expect there to be tension between. And for the most part, people really got on, it was a very friendly and civilized affair. And remarkable for one thing which was that at no point during the day did I hear anybody talking about old times. You know, what people talked about was today or tomorrow in the sense of, “Well how old are your children now?” and “Where are they going to school?” and “Where are you going to holiday next year?” and people would kind of, no one was interested in the past or reminiscing, you know, that was kind of like definitely not what anybody was there for. It was quite extraordinary that they couldn’t get anyone to talk about old times. Not readily, anyway.

Marc Allan: Well, one of the things that I find kind of amazing is that 22 is a few more than I thought there were, but once people left Jethro Tull, they really never did anything, I mean they certainly never did anything of note. I mean, you look back starting from the days of Mick Abraham’s leaving, I never heard a word about Barry Barlow after he left, I never heard a word of John Evan after he left, and it’s kind of curious that–

Ian Anderson: Well then, but most of them sort of opted out of music, I mean John Evan’s left Jethro Tull and went into the building industry. And he runs a quite successful building firm who does most of the renovations on buildings around Heathrow airport. Jeffrey Hammond left Jethro Tull to become a painter, which is what he was before he joined Jethro Tull and he’s done nothing but stay at home and paint pictures since then. Barry Barlow went off into the sort of risky world of record production and management, and, you know, has had mixed fortune since, I think, which you could say. Clive Bunker went up to set up an engineering factory in dog kennels. And Mick Abrahams became a lifeguard but he couldn’t swim. So, hang on a sec

Marc Allan: Sure.

Ian Anderson: Hi Gam, where are you? At the hotel? Hi, sorry, got my daughter en route somewhere in the far part of the country.

Marc Allan: Okay.

Ian Anderson: Yeah, that’s it, okay.

Marc Allan: All right, well I’m hoping I can keep you just a few more minutes, I wanted to ask you a few other things.

Ian Anderson: Yeah, have to be a few, because I’m actually, I should have had a six o’clocker that I’ve gotta ring through right now so we’re not to get too far behind schedule.

Marc Allan: All right, okay then just a couple other things. You’ve touched on this a little bit already, but what’s Jethro Tull’s place in the history of rock gonna be?

Ian Anderson: Well, probably not that important a place, but I imagine Jethro Tull is always gonna be seen as one of those quaint, sort of idiosyncratic bands of the sort of ’70s that sort of, kind of did the stuff that was you know, kind of not the norm and had its brief connection with commercial success but overall was a sort of band that kind of did things that weren’t quite mainstream. I suppose at the end of it all I think I’d rather be in Jethro Tull than be in Guns N’ Roses because, you know, Guns N’ Roses, if they are remembered in 100 years from now in the sort of music books or the history books, they’re gonna be remembered as a band who kind of were a second recycle of a kind of Rolling Stones phenomenon. Just as Metallica will be remembered as a kind of second recycle of the Black Sabbath phenomenon. I mean, Jethro Tull, along with the Emerson Lake and Palmers and Yes, and all of these kind of progressive rock bands of the early ’70s are sort of seen as being slightly kitsch, slightly you know bombastic, overblown, whatever. But at least some people remember our names, and some of us are remembered as musicians, not just as images. I mean you’re gonna remember Keith Emerson was actually a very good keyboard player, you’re gonna remember that guys in Pink Floyd or Yes or whoever, you know, actually had some real command of their instruments, whereas a lot of the bands have really just been kind of imagery, and some pretty faces or around at the right time with the occasional hit record. And I’m not unhappy with the status of Jethro Tull but I don’t think, you know, I wouldn’t place it as being kind of a landmark in the history of rock music, we’re just kind of one of those bands that did some of the stuff that was a little bit on the edge of that more conventional and satisfying mainstream of rock music, which I, as a listener enjoy immensely when it’s good, but you know it’s very very hard to work in that genre and come out with anything original. And these days even harder than ever.

Marc Allan: Bet you’ll be happy with that designation, then.

Ian Anderson: Well, I’m pretty happy with the idea that we were one of those almost, I mean yeah, almost an important band.

Marc Allan: All right, and finally I was hoping that you would look into your crystal ball and tell me what you think music is gonna be like in the year 2000?

Ian Anderson: Ooh, well, I wish I could say that there was gonna be any, I mean we’re only talking, after all, you know, seven years away. It really is not gonna be very different. I mean, rock music as a genre is really changed very very little over the last 20, 30 years. I mean we’re still talking the same essential rhythms, the same tempos, the same fairly simple harmonic relationships. Nothing is really set down to be changed, we’ve had technological changes, but we haven’t had really musical changes. You know, rock is a pretty finite form, it can deal in a currency which is, you know, fairly universal and fairly simple. I don’t think we’re gonna see any great changes, we will see, I mean, for sure for the next 10 years, all we’re gonna see is more recycling of fairly established formats that have been introduced in the last 30 years. I mean we’ve seen revivals of you know, kind of ’60s stuff, and we’ve seen, you know, kinda a lot like we said the Guns N’ Roses, you know, are not 1,000,000 miles away from early Stones and Metallica for Black Sabbath, and you know you look at some of the kinda grungy, sort of post-hippie type bands from Seattle or what have you, I mean they owe a lot to a peculiar mixture of kind of ’60s ideology and MC5 anarchism. We’re kind of recycling all these sort of notions and then patching them together in slightly varied ways. I mean, eclecticism these days is not about the true eclecticism of the perhaps the late ’60s or the early ’70s when people looked at world music as it has now become known, though eclecticism now is just kind of from a very narrow band of proven commercial formulae, which conspire every so often to produce a new hit band that sounds different on first inspection, but in reality is probably just, you know, a careful amalgam of a few proven formulaic approaches to rock music. There’s nothing wrong with that, I mean you know we’re recycling corn flake packets and bottles of nuclear fuel, we might as well recycle rock music as well. Let’s be friendly to the environment.

Marc Allan: If not the ears, yeah. It just seemed to me in asking that question, and I’ll let you go after this, I’m 34 years old and everybody who’s my age or maybe a little older who grew up on rock music probably knows the song Bungle in the Jungle. But now, if Bungle in the Jungle came along it would be a hit on a narrow radio station where you know, lots of kids would never hear it. It would appeal to a certain audience and it seemed to me that the audience of rock has fractured to the point where you can be in a very narrow scope of things and a lot of people will never know what you do.

Ian Anderson: Hmm, which is rather sad when you think of all the bands that there must be out there in any point in time who have some genuine talent and some genuine creative and perhaps even new approach to music who just are not going to be heard. And that is a worrying thing, you know, that we’re talking about recycling a lot of proven ideas because they are sufficiently familiar to those people who operate the media, you know the record companies, the press, the radio stations and TV, you know, we’re dealing with things that sound familiar and proven, they have a track record. They’ve got to sound familiar to the guys who pull the pro strings and you know, allocate time and energy towards specific projects. But, you know there must be a whole bunch of things out there that none of us ever get to hear. And that is very sad, very frightening, but it’s the age in which we live, and music, I think as always, just reflects a lot of other things about the society that we live in at the moment and there is a need to plan to be not too adventurous, to be slightly conservative, slightly right wing, and stay with the things that we know work, you know, the great uncertainty about the planet at the moment and combined with the dangerous forces of nationalism, flag waving extremism, you know, rock music has also, or popular music has also kinda been trenched in staying within the things that are mainstream, things that sound familiar, reassuring, and don’t pose too many big question marks. But the most radical music around, for me, is not you know, rude, rap or you know, funkadelia, or acid, or you know, techno, rave, or any of these sort of absurd definitions that get thrown around, I mean for me I just see just the dying embers of what began in Tamla Motown as sort of a final degradation really for me of what black music was and should still be about. But I don’t hear anything too radical or exciting, and if there is anything radical, exciting, and innovative then it ain’t getting released on record. Or at least not any record label that I know about. And that’s a scary thought, that we’re all having to play a little bit safe these days. But, you know, we’re in the post-Thatcher years, the post-Reagan years, and just everybody’s a little bit nervous right now.

Marc Allan: Very true.

Ian Anderson: With probably very good reason.

Marc Allan: Maybe so. All right I appreciate all your time, I’m looking forward to seeing you, and I hope everything works out the way you like.

Ian Anderson: Well, even if half of it does I wouldn’t have a bad time.

Marc Allan: That’s true, take care Ian.

Ian Anderson: Thank you, bye now.