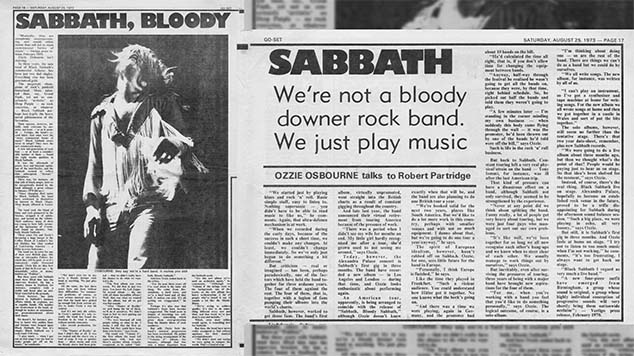

Sabbath, Bloody Sabbath

We’re not a bloody downer rock band. We just play music – OZZIE OSBOURNE talks to Robert Partridge

This article originally appeared in Go-Set magazine on August 25th 1973

by Robert Partridge

GO-SET — SATURDAY, AUGUST 25, 1973

“Musically, they are completely uncompromising, and would rather starve than sell out to more commercial forms of music.” — Vertigo press release, February 1970.

Ozzie Osbourne isn’t starving.

In three years, the sum total of Black Sabbath’s commercial failures has been just two dud singles. Everything else has been guaranteed gold.

The megawatt champions of rock’s punkoid hinterland. More talented than, say, Grand Funk, yet not so consciously “artistic” as Deep Purple — no rock concertos, or whatever — Black Sabbath perhaps best typify the heavy metal phenomenon of the Seventies.

Their success, however, initially took everyone by surprise, not least — or so it seemed — Vertigo, the band’s record label. Just what were the “more commercial forms of music” Black Sabbath swore never to adopt? They were the new commercial music.

A new sub-generation of rock fans — or at least a considerable number of them — found the right macho qualities in Black Sabbath.

It was the aftermath of peace, love and buoyant optimism of the mid-Sixties, and the Sabbath seemed to reflect that subsequent “downer” atmosphere.

There was, for instance, all that talk of black magic, later to be categorically denied by the band although a press release in January 1970 did say: “Since changing their name to Black Sabbath, the band have awakened in themselves an interest in Black Magic. Most deeply affected is Geezer.”

The band took the blend of blues and rock pioneered in the Sixties, stripped it of subtleties, and turned up the volume. Their audience, many of them too young to have fully savored the intricacies of Cream, had found an identity. Sabbath, bloody Sabbath.

Three years on, and Ozzie’s devouring a huge burger in the coffee room of London’s latest Holiday Inn (that symbol of God-fearing America, complete with a Bible in every bedroom).

The band are in town for one of their rare British appearances, this time at Alexandra Palace, for which they will be paid, or so it’s rumored, eight thousand pounds. Ozzie has no idea how much of that he’ll ever see — he mournfully refers to money matters as “Politics.”

But three years with Sabbath must have lifted him into the super-tax bracket. He owns a country house in Stafford, for instance, complete with a stable and horse plus an artificial waterfall in the grounds.

Ozzie, however, has little interest in the trappings. His one involvement is the band, although he makes no statements, no pronouncements about their music.

He doesn’t, for instance, profess to know why sudden fame and fortune were heaped upon Black Sabbath. For him it’s simple: “Black Sabbath are a rock band. Full stop. We just play music — when I get out on that stage I try my best to make people get off on the music.”

“We don’t ever try to say we’re a bloody downer rock band or anything. We just play music.”

All the same, the last three years have not been without their difficulties. No commercial problems, of course, or even serious musical ones. It’s just that the band have picked up enough flak from certain critics to make Ozzie a wee bit cynical.

And it’s not only the critics. In Ozzie’s opinion it’s only recently the band has found the freedom to do what it wants, without outside restraint.

Like record production, for instance:

“The Master of Reality album I didn’t like at all. It was too rushed and the sleeve was a load of crap. It was so quickly done — three weeks and even the bloody sleeve had been printed — that we didn’t really have the chance to do what we wanted to do.

The first album was even worse. We did that in just two days. You know the Led Zeppelin second album — the one with all those incredible effects? Well, that was what we wanted for the album, but all we got was flat sounds.

After Master of Reality we said hump the lot of them, we’ll do it ourselves. We didn’t want to feel we were putting out a load of crap.

I like the first albums, but they could have been done a lot better,” says Ozzie.

“We were browned off with people telling us what to do. I mean, I still like the first albums, but they could have been done a lot better,” says Ozzie.

The result was Volume 4, the first album the band felt super-happy with. And now there’s another album virtually completed, to be called Sabbath, Bloody Sabbath.

And here Ozzie comes back to the critics:

“For the past three years all I’ve read about is the same old thing. We come from Birmingham, a hard town, and we’re a hard band and all that bull. It makes you sick. It’s all getting too exaggerated,” he says.

Perhaps it’s also true that Sabbath’s fears have become exaggerated. The band seem in danger of becoming too self-defensive, something which gives them over-protection from the blunter blows of rock aesthetes.

But still, Ozzie feels the progression is marked. He points to the string arrangement of the Volume 4 album, for instance, although that was only a minor departure from the Sabbath norm.

“On this new album we’ve used an orchestra again,” he comments. “Although on Volume 4 the strings were in the background, one of the tracks on the new album has heavy orchestration. A lot of people who’ve heard it say it sounds a bit like the Moody Blues.

We’re trying to achieve quality. It’s nice to do something different every now and then, and that track we’ve just done is nice and melodic.”

Which, even most critics would agree, is something new for Sabbath.

But then, the band have never really attempted to find critical applause for their musical accomplishments.

“We didn’t start out saying we were to conquer the world. That’s a load of crap.”

“We’re not a bloody downer rock band. We just play music.”

“We started just by playing blues and rock ‘n’ roll. Basic simple stuff, easy to listen to. Nothing supersonic — you didn’t have to be able to read music to like us,” he comments.

“When we recorded during the early days, because of the success in such a short time, we couldn’t make any changes. At least, we couldn’t change immediately. So we’ve only just begun to do something a bit different.”

But criticism — real or imagined — has been, perhaps paradoxically, one of the factors which have held the band together for three arduous years. The four of them against the rest. The four of them, that is, together with a legion of fans pumping their albums into the world’s charts.

Sabbath, however, worked to get those fans. The band’s first album, virtually unpromoted, went straight into the British charts as a result of constant gigging throughout the country.

And late last year, the band announced their virtual retirement from touring America because of the pressure of work.

“There was a period when I didn’t see my wife for months on end. My little girl hardly recognized me after a tour, she’d grown used to not seeing me around,” says Ozzie.

Today, however, the Alexandra Palace concert is Sabbath’s first gig in three months. The band have recorded a new album — in Los Angeles and London — during that time, and Ozzie looks enthusiastic about performing again.

An American tour, apparently, is being arranged to coincide with the release of Sabbath, Bloody Sabbath, although Ozzie doesn’t know exactly when that will be, and the band are also planning to do one British tour a year.

“We’re booked solid for the next two years, places like South America. But we’d like to do a lot more work in this country, perhaps with smaller venues and with not so much equipment. I dunno about that, but we’re going to do one tour a year anyway,” he says.

The spirit of European idealism, however, hasn’t rubbed off on Sabbath. Ozzie, for one, sees little future for the band in Europe.

“Personally, I think Europe is finished,” he says. Like the time they played in Frankfurt: “Such a violent audience. You could understand how Hitler got it together. No one knows what the heck’s going on.”

“And there was a time we were playing, again in Germany, and the promoter had about 10 bands on the bill.

He’d calculated the time all right, that is, if you don’t allow time for changing the equipment between bands.

Anyway, halfway through the festival he realized he wasn’t going to get all the bands on, because they were, by that time, right behind schedule. So, he picked out half the bands and told them they weren’t going to play.

A few minutes later — I’m standing in the corner minding my own business — when suddenly this body came flying through the wall — it was the promoter, he’d been thrown out by one of the bands he’d told were off the bill,” says Ozzie.

Such is life in the rock ‘n’ roll business.

But back to Sabbath. Constant touring left a very real physical strain on the band — Tony Iommi, for instance, was ill after the last American trip.

That kind of pressure can have a disastrous effect on a band, although Sabbath not only survived, they seemed to be strengthened by the experience.

“Never at any point did we think about splitting the band. Funny really, a lot of people get very heavy about touring, but we were just four guys who managed to sort out our own problems.

It’s like well, we’ve been together for so long we all now recognize each other’s hang-ups and we know when to steer clear of each other. We usually manage to work things out by ourselves,” says Ozzie.

But inevitably, even after surviving the pressures of touring, three years of being with a major band have brought new aspirations for the four of them.

“For me, when you’re working with a band you feel that you’d like to do something personally,” says Ozzie. The logical outcome, of course, is a solo album.

“I’m thinking about doing one — so are the rest of the band. There are things we can’t do as a band but we could do by ourselves.

We all write songs. The new album, for instance, was written by all of us.

I can’t play an instrument, so I’ve got a synthesiser and tape machine at home for writing songs. For the new album we all wrote songs at home and then we got together in a castle in Wales and sort of put the bits together.”

The solo albums, however, still seem no further than the tentative stage. There’s that two-year date-sheet, remember, plus new Sabbath records.

“We were going to do a live album about three months ago, but then we thought what’s the point of that? People would be paying just to hear us on stage. So that idea’s been shelved for the moment,” says Ozzie.

Instead, of course, there’s the real thing. Black Sabbath live on stage. Alexandra Palace, hopefully to become an established rock venue in the future, proved to be a trifle disappointing for Sabbath during the afternoon sound balance session. “Such a big place, we were playing in echo, all very boomy,” says Ozzie.

But still, it is Sabbath’s first gig in three months. And Ozzie feels at home on stage. “I try not to listen to too much music when I’m not working,” he comments, “it’s too frustrating. I always want to get back on stage.

Black Sabbath I regard as very much a live band.”

“A new four-piece outfit have emerged from Birmingham, a group whose sound is original, a group whose highly individual conception of progressive sounds will very shortly bring them nationwide acclaim.” — Vertigo press release, February 1970.